There are new ways to learn about A.D.H.D

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the United States: a story from a father and his two boys, an educator and a science enthusiast

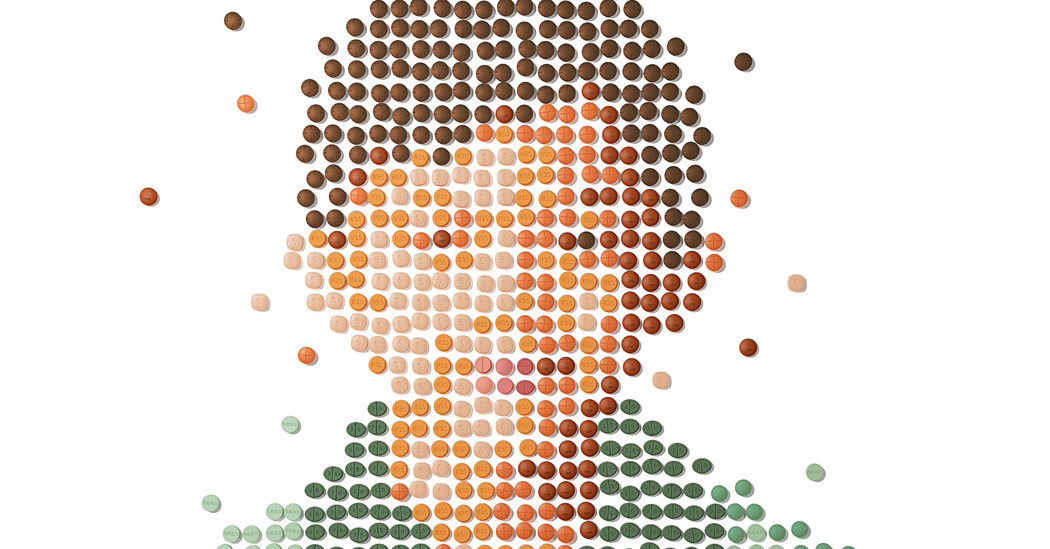

A wraparound story about a surge of A.D.H.D. cases in the United States was published by my colleagues at The Times Magazine. It has been found that 23 percent of 17-year-old boys have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The number of prescriptions rose nearly 60 percent in a decade. You almost certainly know people who take these stimulants.

I have been writing about education and children for decades, and now I have two boys with me. I noticed how many families I met were struggling with their kids’ attention issues. I worried about attention to my kids as well as myself. But I didn’t know much about the science behind attention. So I started talking to scientists. They had a number of big unresolved questions, which I discovered when I did.

What is “A.D.H.D.”? What are the underlying symptom(s) of a child’s anxiety?

There is no test for this. It needs to be diagnosed by it’s symptoms, and those symptoms can be difficult to pin down. One patient’s behavior can look quite different from another’s, and certain A.D.H.D. symptoms can also be signs of other things — depression or childhood trauma or autism. Take a child who is constantly distracted by her anxiety. Does she have A.D.H.D., an anxiety disorder or both?

A new treatment or a better understanding of what causes the underlying symptoms are usually why a diagnosis booms like this. I spent last year interviewing A.D.H.D. scientists around the world for a magazine article, and what I heard from them was that they don’t understand A.D.H.D. The field of A.D.H.D. has had some important discoveries made recently, some of which may lead to a new understanding of the role of the child in the progression of his symptoms.