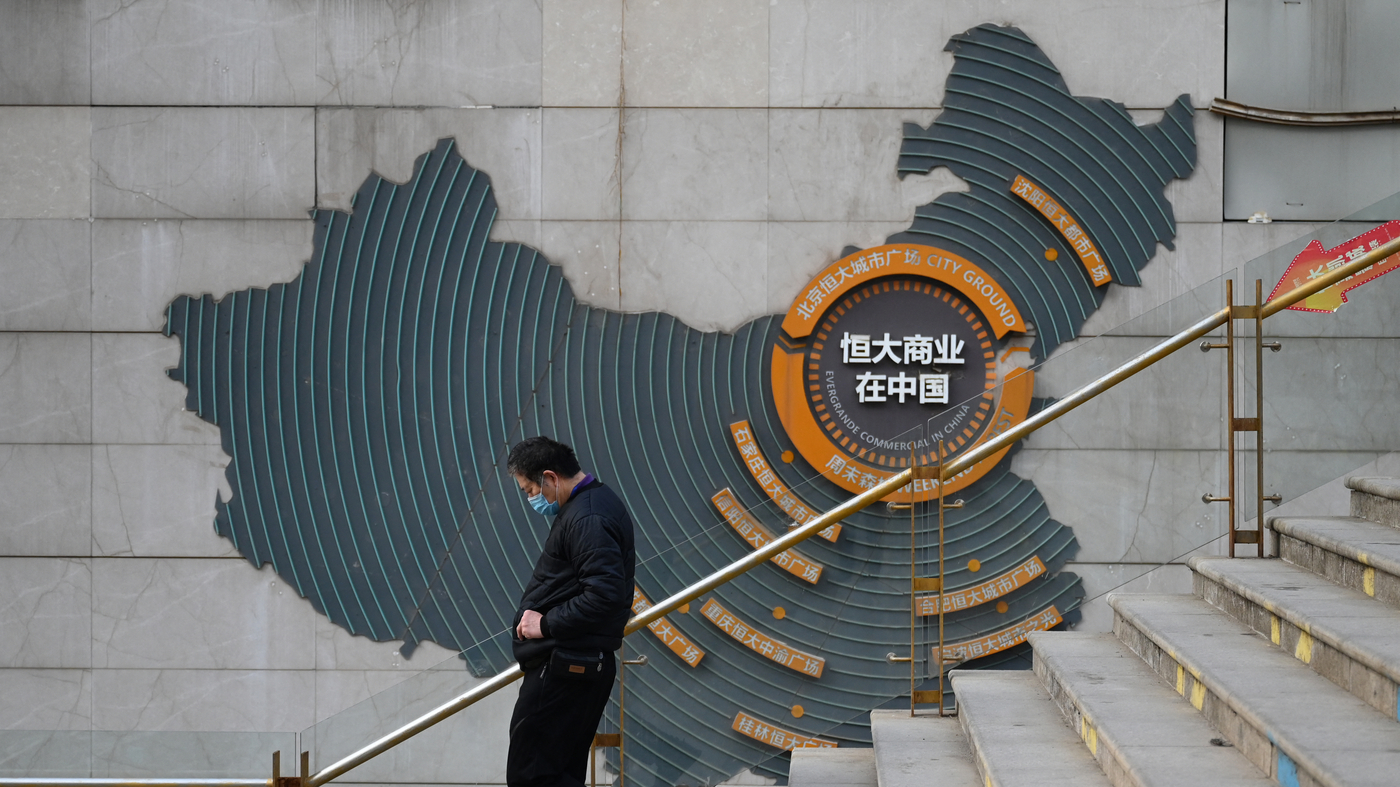

The collapse of China’s Evergrande property developer has been covered in detail

Evergrande facing China’s “three red lines,” a high-growth economic boom inspired by the “three fires” of the real estate sector

Evergrande has been on a slow burn to insolvency since at least 2020, when the Chinese government launched a program, known as the “three red lines,” aimed at deleveraging the real estate market. Beijing restricted how much it could borrow due to the sector’s overheated state.

Judge Linda Chan said Monday it was necessary to order Evergrande to shut down its business because of “lack of progress on the part of the company putting forward a viable restructuring proposal.”

Real estate drove China’s economic boom, but developers borrowed heavily as they turned cities into forests of apartment and office towers. That has helped to push total corporate, government and household debt to the equivalent of more than 300% of annual economic output, unusually high for a middle-income country.

Financial markets were rattled by fears of an Evergrande liquidation. The risks could be contained, Chinese regulators said. Only a few billion dollars of Evergrande’s debt was owed to foreign creditors.

The Evergrande’s Hong Kong- traded shares plummeted early Monday before being suspended from trading. But Hong Kong’s benchmark Hang Seng index was up 0.9% and some property developers saw gains in their share prices.

Evergrande’s Demise and the Chinese Shadow Banking Sector: The Loss of China’s Export-Leading Economy and the Challenges for China

Evergrande “has not demonstrated that there is any useful purpose for the court to adjourn the petition – there is no restructuring proposal, let alone a viable proposal which has the support of the requisite majorities of the creditors,” Chan, the judge, said in remarks published online Monday.

She lambasted the company for putting out only “general ideas” about what it may or may not be able to put forward in the form of a restructuring proposal. The interests of creditors would be better protected if Evergrande is wound up by the court, she said.

The group’s domestic and overseas units are independent legal entities. Siu said that Evergrande will strive to continue smooth operations and deliver properties to buyers.

He said they would make every effort to advance all work fairly and in accordance with the law if they were to be affected.

The fallout from the property crisis has also affected China’s shadow banking industry — institutions that provide financial services similar to banks but operate outside of banking regulations, such as Zhongzhi Enterprise Group. Zhongzhi, which lent heavily to developers, said it was insolvent.

China will be selling a lot of goods that it needs to sell, and they’re going to be selling them on the cheap. I would think that could be a deflationary force.

Similar concerns are what Roberts sees. The U.S. and China, he says, “are deeply entwined,” and most top U.S. multinationals “secure a significant portion of their revenues and profits from the China market or their supply chains start there.”

At first glance, that seems to benefit consumers buying Chinese made goods. Instead, it’s more likely to mean that U.S.-based competitors will need to lower their prices to compete with a flood of ever-cheaper Chinese products.

China is a huge economy, so the United States should keep an eye on it. China would most likely only have to export deflation if it is having a lot of it.

Beijing has come to recognize that an export-led economy on the scale that China has built in recent decades cannot go on forever, and it has tried to promote more domestic consumption to take up some of the slack.

It is unlikely that Evergrande’s demise will affect US consumers, but it is another indication that China’s economy is currently in a state of distress and could result in slower global growth.

Diana Choyleva says the ruling in Hong Kong will affect Evergrande’s investors both foreign and domestic.

Ordinary investors who just wanted to buy an apartment and larger institutional investors who want to invest in Evergrande will need to stand in line as the courts figure out who is going to get paid.

Chinese households have 70% or more of their asset wealth in their apartments. Evergrande’s collapse, although long anticipated, comes as a blow to some, says Roberts.

“At some point, you may not be able to actually complete all of that housing. … Kennedy said that projects get bogged down and the financing situation gets worse.

Evergrande’s Debt Shutdown: The Myth of Chinese Capitalism and a Time-Violating Tragic Event

Evergrande was seeking a $23 billion debt restructuring plan but it fell apart last year after the company’s billionaire CEO was under investigation for criminal behavior.

The dramatic fall of Lehman was due in large part to millions of risky mortgages propping up an unstable financial system. Homebuyers with mortgage payments they couldn’t afford defaulted on their loans, sending shock waves through Wall Street and leaving those borrowers vulnerable to foreclosure.

“It worked,” says Dexter Roberts, director of China affairs at the Mansfield Center at the University of Montana. Evergrande is the biggest victim of that policy.

Roberts is an author of The Myth of Chinese Capitalism and is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub.

Scott Kennedy, senior adviser and Trustee chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, agrees that Evergrande’s downfall should not come as a surprise to either of its investors or the world.