A little electric stimulation may bolster a damaged brain

Improved performance with an implanted neurostimulation device using a magnetic stimulation device to help improve brain function after msTBI

Tests administered to Arata and four other patients who got the implanted device found that, on average, they were able to complete a cognitive task more than 30 percent faster with stimulation than without, a team reports in the journal Nature Medicine.

The improved performance with the device suggests that it is possible to “make a difference years out from injury,” says Little, who is research director at the Trauma and Resilience Center at UT Health.

Many traumatic brain injury stories include damage to the head which causes the brain to die off and lead to long-term cognitive difficulties. More than five million people in the United States suffer from this type of injury which can make it hard for them to resume their normal life and work.

The participants, all of whom had experienced msTBI for at least two years, had surgery to implant electrodes near the lateral side of their thalamus in both brain hemispheres. Researchers spent 14 days tweaking the stimulation parameters for each participant after the surgery. They used implants for a three months time period to carry out an electrical current at 150–185 hertz.

The research team designed treatment approaches for five people who took part in the study using brain scans and atlases.

Deep Brain Stimulation Can Help Brain Injury Patients During the First Year of Rehabilitation: A Case Study on a Multitask Test for Attention and Attention

To test the participants’ cognitive functioning, the researchers used a test that assesses task switching, attention and working memory. People had to connect a series of numbers in the same pattern.

The team hopes to conduct larger trials to continue their work, says the study co-author. They would also like to develop a reliable protocol to train other centres to deliver the treatment.

Even a 10 percent change in function can make a difference in whether or not you are able to return to your job.

If deep brain stimulation proves to be effective in a large study, it could help many brain injury patients who have run out of rehabilitation options.

Henderson says the wires will be put into a device that’s implanted in the chest. “That device can be programmed by someone else.”

So starting in 2018, Henderson operated on five patients, including Arata. All had sustained brain injuries at least two years before receiving the implant.

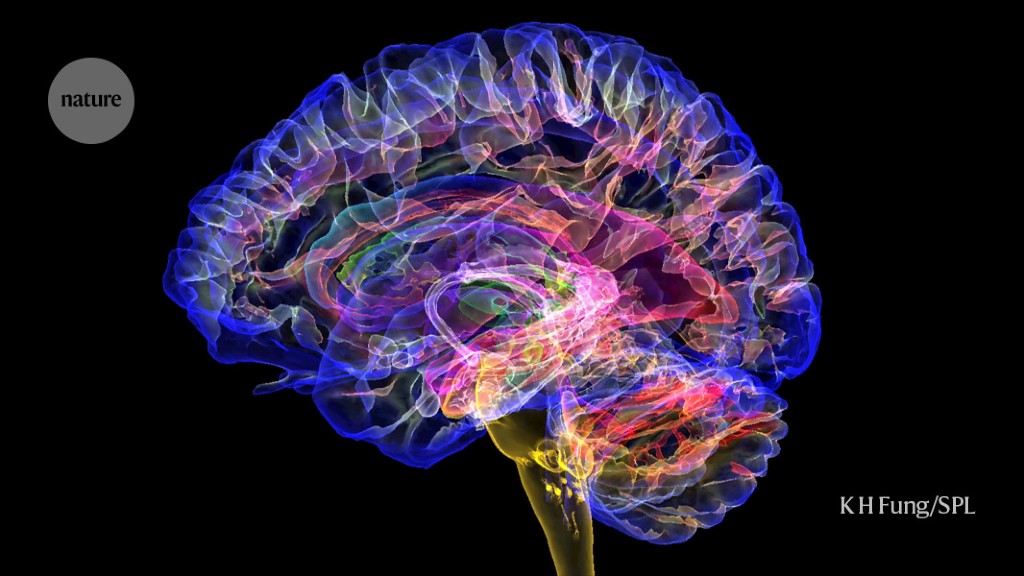

The team hoped that stimulating this hub would help patients like Arata by improving connections with the brain’s executive center, which is involved in planning, focus, and memory.

That region, called the central lateral nucleus, acts as a communications hub in the brain and plays an important role in determining our level of consciousness.

Gina Arata, a minimally conscious person, used deep brain stimulation to find a job in Houston, Texas, where she hasn’t yet

In 2007, he was part of a team that used deep brain stimulation to help a patient in a minimally conscious state. He and Henderson collaborated to explore a similar approach to people like Gina Arata.

The study emerged from decades of research led by Dr. Nicholas Schiff, an author of the paper and a professor of neurology and neuroscience at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

The results “show promise and the underlying science is very strong,” says Deborah Little, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at UT Health in Houston.

When the stimulation was turned on, Arata could list lots of items found in, say, the produce aisle of a grocery store. When it was off, she had trouble naming any.

Arata hasn’t gotten a job yet. Two years ago, while studying to be a dental assistant, she was unable to do so because of a rare condition that damaged her spine.