Sam Bankman- Fried could face decades in prison after he was found guilty of all charges

Bankman-Fried vs. Cohen: On the Case for a Wall Street Man, Not a Business Person? The Case Against Cohen

We learned Bankman-Fried was working very hard, 12 hours a day, which seemed low: Bankman-Fried had previously testified he worked as many as 22 hours a day. There was precious little testimony about what he was doing, so I couldn’t tell you what he was doing. I heard a lot about the data protection policy that the defense couldn’t produce.

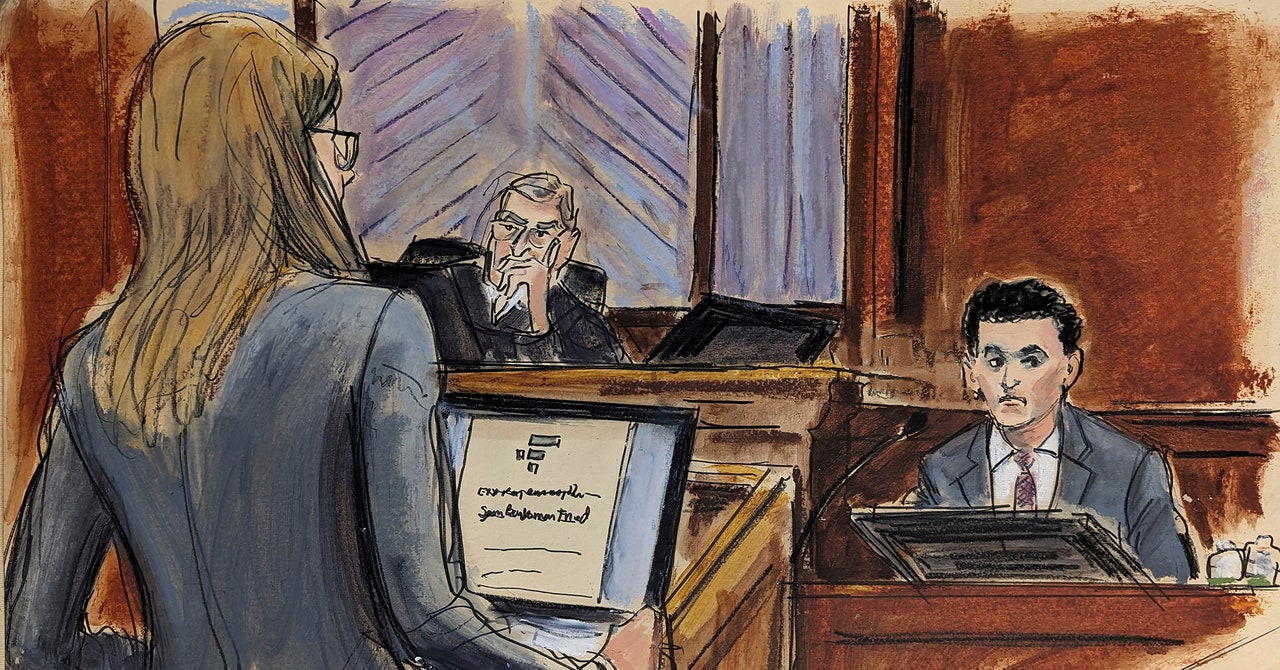

The closing arguments made clear how large the case was. According to Bankman- Fried’s defense, he is a nice boy who would never hurt anyone on purpose. An introvert! Who doesn’t use recreational drugs? When Cohen asked the jury to keep him in mind as they deliberated, Bankman-Fried crumpled the water bottle in his hand, making a noise. He looked at the jury, with a expression on his face that suggested he might cry.

Cohen introduced matters that I think were meant to confuse the jury, but seemed to merely bore them. During a long digression about Alameda’s net asset value, for instance, I saw several jurors glance at the clock at the back of the courtroom. The same went for discussion of FTX’s risk engines.

We still have to hear the prosecution’s rebuttal to Cohen’s arguments, such as they were, before the case goes to the jury. Even the most skilled defense lawyer would have a hard time with this case. The documentary evidence for the prosecution is just too overwhelming, and there’s very little evidence to back Bankman-Fried’s telling of events, which contradicts all three cooperating witnesses — and Yedidia, who hasn’t been charged with anything. Bankman-Fried told the jury he liked to lie and they established that at the length of the story.

The defense attempted to argue that Bankman-Fried acted as any rational businessperson would, amongst trying market conditions, and never intended to defraud anyone. Bankman-Fried even took the stand himself, against conventional legal wisdom, to appeal directly to the jury’s sympathies. But confronted with testimony from members of Bankman-Fried’s inner circle, who spoke of their own guilt, as well as customers and investors that lost money in the fall of FTX, the jury found against the defendant.

The closing statement could have ended after the first hour. The evidence that Bankman-Fried was involved — from his Google Meet with the other alleged co-conspirators, to the metadata linking him to various incriminating spreadsheets, to the funds traced to entities he controlled — would have been enough. But we got a few more hours anyway, as though Roos had rented a backhoe for his pile of evidence and was going to get as much use out of it as possible.

The jury was focused on him as he spoke. No one seemed to be sleeping. I didn’t see anyone glance at the clock; many jurors were taking notes. Though Roos was interrupted by an AV mishap when the screens used to show the jurors the evidence briefly went out in the middle row, the closing argument was smooth. Roos talked directly to the jury, glancing occasionally at his own notes.

I realized that the defense had been jumping around so much because I was watching Roos. His chronological order showed he was learning and lying about things. Four hours later, Bankman-Fried explained an $8 billion gap between what he owed customers and what FTX could pay in a Signal chat.

Cohen emphasized that mistakes aren’t illegal. He wanted to show Alameda and FTX as innovative businesses. It was sort of hard to understand exactly what they were innovating or how, but never mind. It is certainly true that at its peak, FTX’s valuation was very high.

The fate of a black-collar criminal mastermind: the story of Bankman-Fried as a FTX customer, and how it collapsed

Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the trial came when Bankman-Fried testified in his own defense — something most white-collar criminal defendants don’t do.

Bankman-Fried was agonizing prosecutors and the court during the months ahead of his trial. In August, he was sent to jail for violating the terms of his house arrest by using a virtual private network to watch a football game and leaking his ex-girlfriend’s diary entries.

During a trial that lasted more than four weeks, prosecutors sought to prove that Bankman-Fried had been a criminal mastermind who orchestrated one of the largest financial frauds in history.

The government said the former billionaire used FTX customer funds to make political donations, and to buy luxurious real estate for friends and family.

“This was a pyramid of deceit built by the defendant on a foundation of lies and false promises, all to get money,” Asst. The closing argument was told by the U.S. Attorney. “And eventually it collapsed, leaving countless victims in its wake.”

The conviction marks a dramatic reversal of fortune for the now 31 years old M.I.T. graduate who just a year ago was living large in a $35 million apartment with his co-workers, as he ran a multimillion dollar empire that was estimated to be worth tens of billions of dollars

Instantly recognizable by his unkempt hair, he was feted at convention and went out with celebrities like former quarterback Tom Brady.

How Bankman-Fried Met, and What He Has Learned About His Ex-Extractors, Caroline Ellison, and Other Managers

Then, one by one, Bankman-Fried’s former executives started to turn against him, including Caroline Ellison, who headed Alameda at one point, and was also his on-again, off-again girlfriend.

Gary Wang, co-founding Alameda Research and FTX with Bankman-Fried, pleaded guilty to one charge and agreed to cooperate with federal prosecutors.

They said Bankman-Fried told them to commit crimes, and their comments were compelling because they were not just Bankman-Fried’s colleagues, but also some of his closest friends.

Bankman-Fried was put to the sword by Danielle Sassoon, a prosecutor who clerked for Antonin Scalia.

Sassoon used Bankman-Fried’s comments to show that there was a stark difference between what Bankman-Fried said in public, and how he acted behind the scenes.

For example, when FTX was teetering on the brink, Bankman-Fried told his hundreds of thousands of followers on X, formerly known as Twitter, it was in sound shape, even as prosecutors claimed he knew that couldn’t have been farther from the truth.

The prosecution painted a different picture of Bankman-Fried than the defense did, claiming that he was a math nerd and not a movie villain.

Bankman-Fried was an inexperienced executive who was unable to keep tabs on what was happening at two big companies or supervise executives at the companies, according to the defense.

In his closing argument, Bankman-Fried’s lawyer, Mark Cohen said Bankman-Fried made mistakes, but argued he always acted in good faith and never intended to commit any crimes.

Cohen said that people misjudge things in the real world. “They hesitate. They don’t plan for the unexpected. They make good and bad business decisions, and they make mistakes that later on they wish they could have fixed.”

The Bankman-Fried conviction at the US Department of Justice: a landmark case for crypto-encryption investigations and prosecutions

The US Department of Justice (DoJ), says Estes, will consider Bankman-Fried’s conviction a “signature victory,” as its first high-profile crypto scalp. Cryptocurrency has been used for more than a decade to conceal payment for illicit products, enable extortion-based cyberattacks and launder the proceeds of criminal activity. In 2021, the DoJ announced the formation of a specialist crypto enforcement team, to “tackle complex investigations and prosecutions of criminal misuses of cryptocurrency,” it said. The agency has secured few landmark convictions.