The strike could last a long time

The Ford Forklift Union: How Ford, GM and Stellantis have a Future Together – A Conversation with Jeremiah Mullins

Ford, GM and Stellantis have all been highly profitable for the last few years, and the union is arguing that much more of that wealth can and should flow to the people who build the vehicles.

“There’s money there,” Mullins says. “I get that we can’t have everything we asked for … Let’s face it, it’s negotiations. You gotta start somewhere.”

The union’s push is personal for him. It’s about getting the kind of pay he can get and the kind of retirement his dad and grandfather will have.

“We must take a stand for something and we have to be true to ourselves and that’s what we gotta be,” she says. “This should have happened a long time ago when everyone gave up their stuff and never got it back.”

Mullins now works in material handling, driving a high-low – a forklift. He works just as hard as the coworkers picketing next to him on a crisp fall morning.

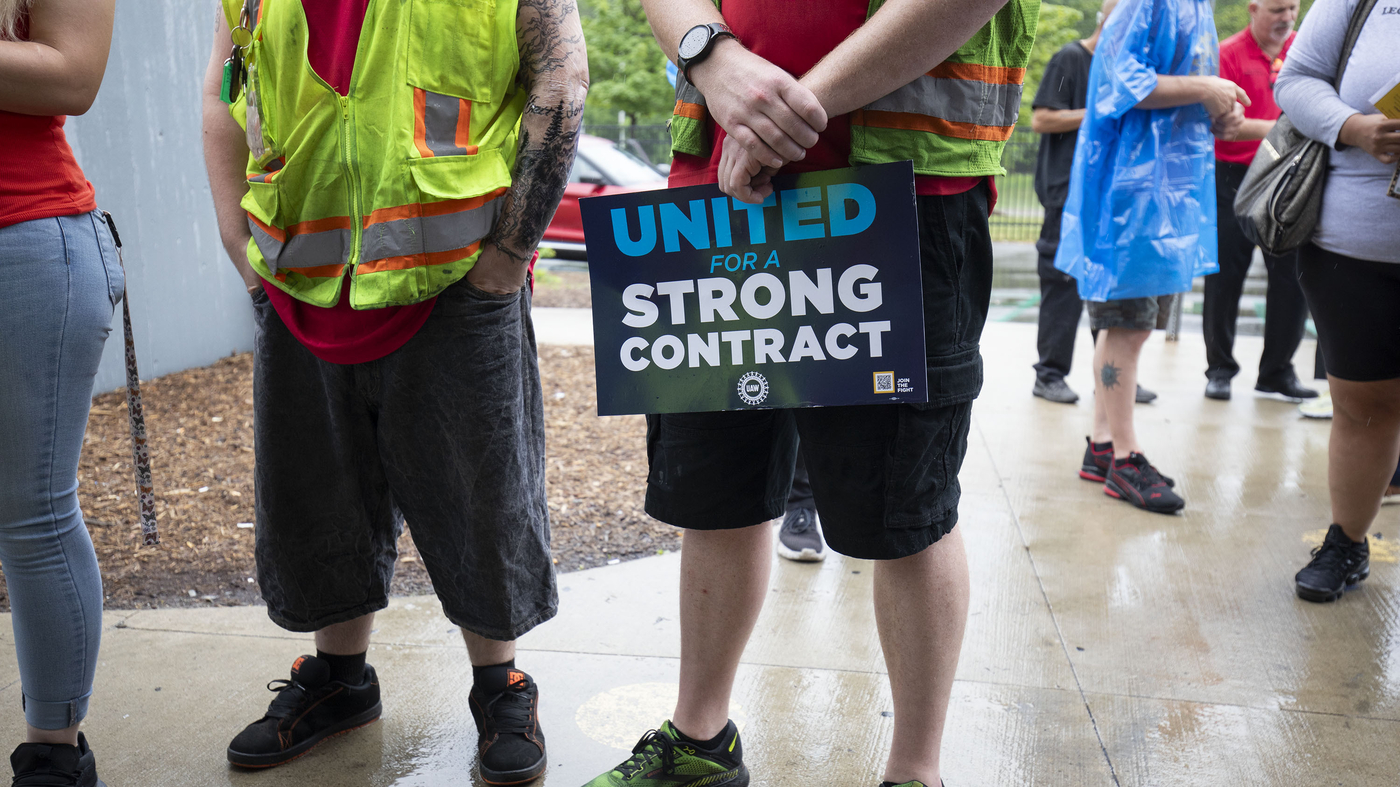

As he stands near one of his factory’s gates, holding a sign, most of the drivers that pass by honk in support. When a heckler drives by, Mullins would remember wrestling with those same tires.

His three years with Ford have culminated in his current position at the company. He remembers his first days on the line vividly. He had one minute per car to keep up, as he heaved the heavy wheels and tires onto the vehicles and worked on the lug nuts.

The Strike Against Auto Workers: The Case Against 401k Retirement in General Relativity, The Case Of Rob Mullins

Mullins, for instance, will get a 401k in retirement. That’s commonplace in today’s workforce but once it was different for UAW workers. Mullins’ dad was also a union member — and he has a far sweeter deal waiting for him when he retires.

These days, workers who are at the companies for long enough can eventually earn the same pay as their colleagues hired before 2007. But the union wants that timeline to be faster.

But it’s gradually escalating the strike, instead of having all of its 146,000 auto workers walk off their jobs at once. The approach is meant to keep the companies from knowing how long they can survive a strike without having a big hit to their business.

“Rob has been here since ’88 and Sofus has been here just as long,” he says. I do what they make double what I do. And yes, I do the same job. I work with Rob every day. Same job, the same skills.

When UAW strikes aren’t at the heart of the companies: GM, Cox and other auto-employees know what they can do

The UAW strike fund provides some benefits, but it does not cover dental and vision, among others.

Striking workers will feel the pinch as weeks go on. But Kyle Bendert, who has been on strike for nearly three weeks at the Ford assembly plant in Wayne, Michigan, said taking a temporary pay cut is worth it if workers eventually “get the contracts we deserve.”

So far, the UAW has refrained from targeting the most profitable sectors of the companies’ production – a strategy that, if maintained, positions the companies to withstand an ongoing strike for many months.

“They’re not hitting at the heart of the companies,” said Sam Fiorani, vice president of global vehicle forecasting at Auto Forecast Solutions. “They’re allowing the companies to still stay in business – and just giving them enough pain to stay at the table.”

Pick-up trucks and large SUVs are the “bread and butter” of the Detroit 3, said Michelle Krebs, executive analyst at Cox Automotive, adding that this is the time of year – leading up to the winter months – when sales go up for these highly-profitable vehicles.

David Whiston, an auto stock analyst at Morningstar, estimates that if workers were to go on strike at all facilities, GM could hold out for six months and Ford for ten months, before reaching the minimum level of cash needed to run their business.

The UAW has made it clear that it is going to tighten the screws as it tries to pressure the manufacturers to reach agreements sooner rather than later.