The Supreme Court could make a decision that ends social media companies

The Case of Nohemi Gonzalez v. Google: A Section 230 and its Implications for the Internet, Google, and the FCC

Section 230 was the reason why the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected this argument last year. Yet the court was not enthusiastic in ruling against the Gonzalez family, with Judge Morgan Christen writing for the majority that despite its ruling, “we agree the Internet has grown into a sophisticated and powerful global engine the drafters of § 230 could not have foreseen.” Judge Ronald Gould argued that Section 230 does not apply to Gmail because the amplification of videos from the Jihadi group contributed to the group’s message. Gould doesn’t believe that Section 229 will protect a social media company’s role as a channel of communication for terrorists in their recruiting campaigns. After the Ninth Circuit largely ruled against the Gonzalez family, the Supreme Court this year agreed to review the case.

Like many Section 230 cases, Gonzalez v. Google involves tragic circumstances. The plaintiffs are the family members and estate of Nohemi Gonzalez, a California State University student who, while studying abroad in Paris, was killed in the 2015 ISIS shootings along with 128 other people. The lawsuit claims thatYouTube gave assistance to terrorists and violated the Anti-Terrorism Act. The dispute is more than just that YouTube hosted some of the videos from the terrorist group, as the lawsuit states in their legal filing. Users who were interested in videos from the Islamic State were targeted based on their characteristics by the plaintiffs, who wrote that they were selected to whom they would recommend the videos. According to the reports, ISIS videos were shown to those who were more likely to be radicalized.

As the Supreme Court ponders whether to hear more Section 230 cases with implications, Members of Congress have expressed renewed enthusiasm for rolling back the law, as do President Joe Biden.

The law holds that websites can not be treated as the publishers or speakers of other people’s content. Any legal responsibility attached to publishing a piece of content ends with the person who created it, not the platforms on which the content is shared, according to plain English.

Conservatives say that Section 230 lets social media platforms suppress right-leaning views, so they have criticized it for years.

The FCC is not a part of the judicial Branch, it does not regulate social media or content moderation decisions, and is an agency that doesn’t take direction from the law make the executive order problematic.

The Supreme Court is almost certain to take up other Section 230-related cases in the next few years — including a decision on laws banning social media moderation in Texas and Florida. The Biden administration has a chance to make a position on internet speech, thanks to the court’s request for briefs from the US solicitor general.

The result is a bipartisan hatred for Section 230 even if the two parties can’t agree on what to do with it.

The US Supreme Court has an opportunity this term to dictate how far the law is able to go after the stalemate gave the courts more authority to change Section 230.

The Defamation League vs. Twitter: Suppressing Terrorism on Social Media with a Section 230 Liability Shield

The courts have been kept away from the social media industry, as it has grown. It is highly irregular for a global industry that wields staggering influence to be protected from judicial inquiry,” wrote the Anti-Defamation League in a Supreme Court brief.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the tech industry it is possible that the internet may change.

“‘Recommendations’ are the very thing that make Reddit a vibrant place,” wrote the company and several volunteer Reddit moderators. “It is users who upvote and downvote content, and thereby determine which posts gain prominence and which fade into obscurity.”

The legal regime would make it too risky for people to recommend a defamatory post on the site, and would force people to stop using it.

The law does not have a defined boundaries, which is why the lawsuit claims that it is protected by Section 230. Section 230 does not contain specific language regarding recommendations, and does not give a legal standard governing recommendations, according to yesterday’s legal filing. They’re asking the Supreme Court to find that some recommendation systems are a kind of direct publication — as well as some pieces of metadata, including hyperlinks generated for an uploaded video and notifications alerting people to that video. By extension, they hope that could make services liable for promoting it.

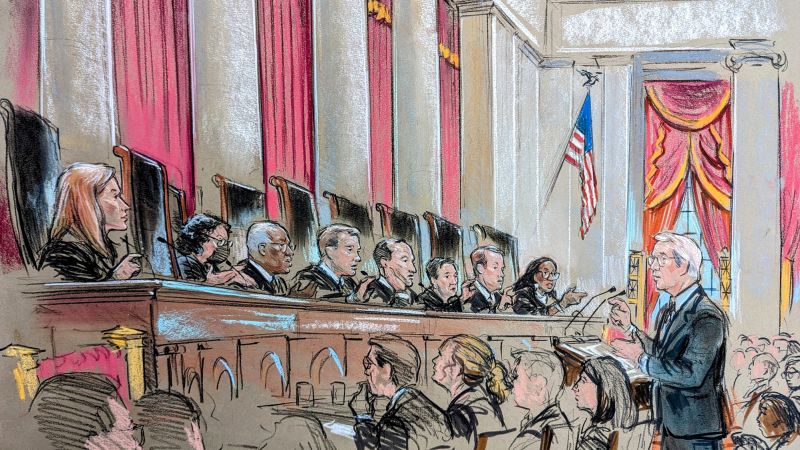

The court heard a case on Wednesday, which looked into the liability of social media companies for aiding and abetting terrorism by hosting content that supports the group behind the act of violence. If the company had been warned that specific accounts were planning an attack, it is possible that they could have been liable, but not because they didn’t know about it.

His question sought to explore what might really happen in a world where the Court rolls back a 27-year-old liability shield, allowing tech platforms to be sued over how they host and display videos, forum posts, and other user-generated content. The outcome in the Google case is viewed as pivotal because it could have consequences for websites large and small, and for workers and consumers, retirement plans and other things.

Representing the terrorism victims against Google and Twitter, lawyer Eric Schnapper will tell the Supreme Court this week that when Section 230 was enacted, social media companies wanted people to subscribe to their services, but today the economic model is different.

“Now most of the money is made by advertisements, and social media companies make more money the longer you are online,” he says, adding that one way to do that is by algorithms that recommend other related material to keep users online longer.

Social media companies must no longer have their cake and eat it too. They shouldn’t be allowed to keep earning money from the inciting of violence because they failed to quickly deploy the resources and technology to prevent it.

The State of the Internet: Where is the Future? Why is the Internet and the Internet? How the Supreme Court is now in a moment where we can protect the freedoms of 230

“The attorney general, the director of the FBI, the director of national intelligence, and the then-White House chief of staff . . . those government officials . . . He says that he told them exactly that.

She says that “we believe that there’s no place for extremists on our products or platforms.” She says that “smart detection technology has been invested in to make sure that happens.”

Prado acknowledges that social media companies today are nothing like the social media companies of 1996, when the interactive internet was an infant industry. The courts should not change the law if Congress is going to do so, she says.

He says that Congress had a clear choice. Was the internet going to be regulated the same way as the broadcast media? Was it going to be like the town square or the printing press? Congress, he says, “chose the town square and the printing press.” But, he adds, that approach is now at risk: “The Supreme court now really is in a moment where it could dramatically limit the diversity of speech that the internet enables.”

Many tech company allies have bedfellows in this week’s cases. The Chamber of Commerce, libertarians and other groups have all urged the court to leave the status quo in place.

But the Biden administration has a narrower position. The administration’s position is summarized by a Columbia law professor, who says: “It is one thing to be more passive presenting, even organizing information, but when you cross the line into really recommending content, you leave behind the protections of 230.”

In short, hyperlinks, grouping certain content together, sorting through billions of pieces of data for search engines, that sort of thing is OK, but actually recommending content that shows or urges illegal conduct is another.

The economic model of social media companies would be in danger if that position was adopted by the Supreme Court. The tech industry says there is no easy way to distinguish between aggregating and recommending.

The companies would be defending their conduct in court. It’s not a good idea to file suit if you have to show enough evidence to justify a trial. The Supreme Court has made it much more difficult to jump that hurdle. The second case the court will hear this week is about that problem.

Tech companies big and small have been following the case, fearful that the justices could reshape how the sites recommend and moderate content going forward and render websites vulnerable to dozens of lawsuits, threatening their very existence.

But Eric Schnapper, representing the plaintiffs, argued that a ruling for Gonzalez would not have far-reaching effects because even if websites could face new liability as a result of the ruling, most suits would likely be thrown out anyway.

One of the few justices focusing on how changes to Section 230 could affect individual internet users was Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who repeatedly asked whether narrowing the law in the ways Schnapper has proposed could put average social media users in legal jeopardy.

You are creating a lot of lawsuits. “Really, anytime you have content, you also have these presentational and prioritization choices that can be subject to suit.”

If websites became liable for their automated recommendations, it could affect newsfeed-style content ranking, automated friend and post suggestions, search auto-complete and other methods by which websites display information to users, other companies have said.

If the same recommendation algorithm encourages people to watch an Islamic State video to someone who is also interested in cooking, the court should treat it differently.

Many of the justices lost their minds when Schnapper speculated about the difference between video and thumbnail images, even though he tried several explanations.

It might be difficult to say that you can be held responsible for terrorist activities even if they use the same algorithms across the board.

Justice Department lawyer Stewart was asked by Barrett if the issue was still relevant. She asked: “So the logic of your position, I think, is that retweets or likes or ‘check this out’ for users, the logic of your position would be that 230 would not protect in that situation either. Correct?”

Stewart said there was distinction between an individual user making a conscious decision to amplify content and an algorithm that is making choices on a systemic basis. Stewart did not give a detailed explanation about how changes to Section 230 might affect individual users.

“People have focused on the [Antiterrorism Act], because that’s the one point that’s at issue here. But I suspect there will be many, many times more defamation suits,” Chief Justice John Roberts said, while pointing to other types of claims that also may flood the legal system if tech companies no longer had broad Section 230 immunity.

Justice Samuel Alito posed for Schnapper a scenario where a competitor of a restaurant created a video making false claims about the restaurant violating health code and YouTube refusing to take the video down despite knowing its defamatory.

When Alito asked what would happen if the platform recommended a false competitor video and it was called the greatest video of all time, he didn’t mention anything about the content.

Though Google’s attorney, Lisa Blatt, did not get the tough grilling that Schnapper and Stewart received, some justices hinted at some discomfort with how broadly Section 230 has been interpreted by the courts.

The internet would have never got off the ground if everyone would have sued, according to Jackson.

The brief, written by Oregon Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden and former California Republican Rep. Chris Cox, explained that Section 230 arose as a response to early lawsuits over how websites managed their platforms, and was intended to shelter the nascent internet.

The Sotomayor Hypothesis, Judge Barrett’s Questioning and the Future of the Internet: How Does the Supreme Court Agree with Section 230?

If search engines created to be discriminate were to be used, platforms could be held liable according to questions posed by Justice Sotomayor. She put forth an example of a dating site that wouldn’t match individuals of different races. The hypothetical was the topic of Justice Barrett’s questioning.

Multiple justices, even though they were not sympathetic to tech foes, suggested that the warnings they gave the court about how a ruling againstGoogle would transform the internet were Chicken Little.

Alito asked if the internet would be destroyed if it was taken down for posting false and defamatory videos.

Do you think we need to go to Section 230 if you lose tomorrow? Would you concede that you would lose on that ground? He asked Schnapper.

Even if there are different legal questions in the case, the facts are the same. And that is why a finding by the Supreme Court that there is no liability under the Act may solve the case without having to deal with Section 230.

If the Supreme Court narrowed the scope of a law, the future of the internet would be determined by a group of justices.

On several occasions, the justices said they were confused by the arguments before them – a sign that they may find a way to dodge weighing in on the merits or send the case back to the lower courts for more deliberations. At the very least they seemed spooked enough to tread carefully.

Family Litigation Claims for the Violation of a U.S. Constitution on Tortuations in the Antiterrorism Act of 1990

The family sued under a federal law called the Antiterrorism Act of 1990 , which authorizes such lawsuits for injuries “by reason of an act of international terrorism.”

Concerns about the way technology is used, as well as concerns about the way restaurant reviews are written, were raised in oral arguments. At the end of the day, the justices seemed dissatisfied with the amount of arguments they were hearing and unsure about the road ahead.

“I’m afraid I’m completely confused by whatever argument you’re making at the present time,” Justice Samuel Alito said early on. “So I guess I’m thoroughly confused,” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said at another point. “I’m still confused,” Justice Clarence Thomas said halfway through arguments.

Justice Elena Kagan even suggested that Congress step in. “I mean, we’re a court. These things are not something that we know about. You know, these are not like the nine greatest experts on the internet,” she said to laughter.

John Roberts was attempting a comparison with a book seller. He suggested that Google recommending certain information is no different than a book seller sending a reader to a table of books with related content.

The Future of Social Media: What Will We Learn If ISIS is Using Twitter? Justice Samuel Alito of the US Supreme Court Presented at High-Stakes

One prominent example of this supposedly “biased” enforcement is Facebook’s 2018 decision to ban Alex Jones, host of the right-wing Infowars website who later was slapped with $1.5 billion in damages after harassing the families of the victims of a mass shooting.

Editor’s Note: Former Amb. There is a non-profit organization that is dedicated to developing technologies and policies to expedite the permanent reduction of hate and extremism on social media platforms. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

The platforms have low liability exposure for customers that decide to post onto that space, as they are benign providers of digital space. It was thought that internet service companies would face financial ruin from a lot of lawsuits for publishing defamation content on their websites.

The internet’s early days have changed. Extremists and terrorists have weaponized platforms. They have been used to incite racially and religiously motivated attacks across the US. And the American people are paying the price in terms of lives lost.

Advertisers have to rely either on the platforms’ assurances they will delete offensive content, or hope that watchdog groups or community members will flag extremist content that they surely would not want their brands to be associated with. Meanwhile, days to months can go by before a platform deletes offensive accounts. In other words, advertisers have no ironclad confidence from social media companies that their ads will not wind up sponsoring extremist accounts.

During Wednesday’s oral arguments, the justices’ questions collectively suggested the Court was leaning in support of Twitter’s defense: that even though ISIS was using Twitter, that does not mean that Twitter was intentionally providing assistance to enable ISIS to commit a specific act of terror.

Justice Samuel Alito of the US Supreme Court asked this week what may be, to millions of average internet users, the most relatable question to come out of a pair of high-stakes oral arguments about the future of social media.

“I suspect there would be many, many times more defamation suits, discrimination suits… infliction of emotional distress, antitrust actions,” Roberts said Tuesday, ticking off a list of possible claims that might be brought.

Websites would face a terrible choice in that scenario, they have argued. One option would be to preemptively remove any and all content that anyone, anywhere could even remotely allege is objectionable, no matter how minor — reducing the range of allowed speech on social media.

Another option would be to stop moderating content altogether, to avoid claims that a site knew or should have known that a piece of objectionable material was on its platform. CompuServe, an online portal, was not liable for libelous contents in a 1991 case because they did not know about it.

Without a specific scenario to consider, it’s hard to grasp how all this would play out in practice. Several online platforms have told the court how they might change their operations.

Section 230, Wikipedia, and the Laws of the Tallahassee Supreme Court: Where Do We Stand? Where Should We Go?

Wikipedia has not explicitly said it could go under. But in a Supreme Court brief, it said it owes its existence to Section 230 and could be forced to compromise on its non-profit educational mission if it became liable for the writings of its millions of volunteer editors.

In that interpretation of the law, Craigslist said in a Supreme Court brief it could be forced to stop letting users browse by geographic region or by categories such as “bikes,” “boats” or “books,” instead having to provide an “undifferentiated morass of information.”

If Yelp could be sued by anyone who felt a user restaurant review was misleading, it argued, it would be incentivized to stop presenting the most helpful recommendations and could even be helpless in the face of platform manipulation; business owners acting in bad faith could flood the site with fraudulent reviews in an effort to boost themselves, but at the cost of Yelp’s utility to users.

Microsoft said that Section 230 wouldn’t protect it from being unable to suggest new job openings to users of Linkedin or connect software developers to interesting and useful software projects on the online code repository GitHub.

The sweeping, seemingly unbounded theory of liability advanced by Schnapper seemed to make many justices, particularly the Court’s conservatives, nervous.

Even if she did not buy his opponent, there was still uncertainty about going the way you would have us go because of the difficulty of drawing lines in this area.

But a potentially greater threat to free speech was taking place more than 800 miles to the south in Tallahassee, where a Florida state legislator proposed a bill to make it easier for plaintiffs to bring defamation lawsuits. A federal judge recently struck down a New York law that regulated online hate speech. A judge in Californianixed a misinformation law. And in DC, the justices are also considering whether to rule on the constitutionality of Texas and Florida laws that restrict the ability of social media platforms to moderate user content.

Sullivan is needed for that commitment according to some justices. Clarence Thomas, a justice on the Supreme Court, has written three times that he wants the court to revisit Sullivan because of the real world effects of the case. Changes to social media have helped Justice Neil Gorsuch join his call. Private people can become public figures on social media in a matter of hours. “Individuals can be deemed ‘famous’ because of their notoriety in certain channels of our now-highly segmented media even as they remain unknown in most.”