Crispr is used to cure HIV

The Dsseldorf HIV-Free Patient: Finding a Way Out of the Rheumatoid and Imposing the Problems It Creates

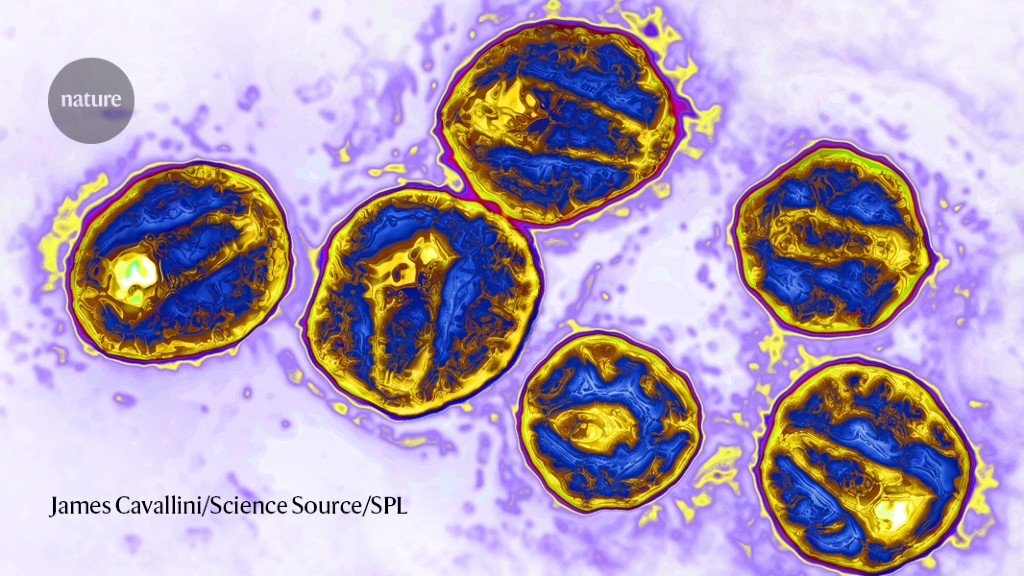

While antiretroviral drugs can halt viral replication and clear the virus from the blood, they can’t reach these reservoirs, so people have to take medication every day for the rest of their lives. The hope is that Crispr will remove HIV for good.

Later this month, the volunteer will stop taking the antiretroviral drugs he’s been on to keep the virus at undetectable levels. If the virus persists 12 weeks, investigators will be able to determine whether it is still present. They would consider the experiment a success if it wasn’t successful. The CEO of Excision said that they were attempting to return the cell to a normal state.

Antiretroviral therapy is given to people with HIV with the aim of lowering it to almost zero levels and preventing it from being transmitted to others. But the immune system keeps the virus locked up in reservoirs in the body, and if an individual stops taking ART the virus can begin replicating and spreading.

That was an important step toward testing the treatment in people, says Kamel Khalili, a professor of microbiology at Temple University who led the work and is a cofounder of Excision Biotherapeutics. “You don’t want to eliminate the viral genome but at the same time cause any disruption in another part of the human genome and then create another set of problems for the patients,” he says. “We had to make sure that we identified a region within HIV that did not overlap with the human genome.”

It is too early to say whether stem cells from donors with a CCR532/32 mutation are virus-free, but Jensen claims that his team has performed transplants on several other people with both HIV and cancer. His team plans to study whether, if a person has a larger reservoir of HIV at the time of receiving a transplant, this affects how well the immune system recovers and eliminates any remaining viruses from the body.

A true cure would eliminate this reservoir, and this is what seems to have happened for the latest patient, whose name has not been released. The man, who is being referred to as the Dsseldorf patient, stopped taking ART and has been HIV-free since.

In 2019, researchers revealed that the same procedure seemed to have cured the London patient, Adam Castillejo. And, in 2022, scientists announced that they thought a New York patient who had remained HIV-free for 14 months might also be cured, although researchers cautioned that it was too early to be certain.

Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, who led the team that treated Castillejo, says the latest study “cements the fact that CCR5 is the most tractable target for achieving a cure right now”.

The patient who received the treatment said in a statement that the bone marrow transplant had been a “very rocky road”, adding that he planned to devote some of his life to supporting research fundraising.

Timothy Henrich, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, says the study is very thorough. Many patients have been successfully treated with a combination of ART and HIV resistant donor cells and the chances of achieving an HIV cure are very high.

But it’s unlikely that bone-marrow replacement will be rolled out to people who don’t have leukaemia because of the high risk associated with the procedure, particularly the chance that an individual will reject a donor’s marrow. Several teams are testing the potential to use stem cells taken from a person’s own body and then genetically modified to have the CCR5Δ32/Δ32 mutation2,3, which would eliminate the need for donor cells.