It is showing how it is adding to sea-level rise

The Changing Coastline of West Antarctica as Observed by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITHS)

The observations, published in two papers in Nature on 15 February1,2, could help to pin down one of the biggest uncertainties in current projections of rising global sea levels. Some studies show that models of how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet responds to climate change are missing some information. Understanding how and why the ice will change in the future is important.

A team from the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration traveled to the glacier to better understand the changing of the coastline.

The scientists found that the melt rate on the underside of the ice was just two to five metres per year, much lower than predicted by models. That was a big surprise to Davis.

The research shows that the water at the base of the glacier has a layer of fresh water between it and the ocean.

The complete collapse of the Thwaites itself could lead to sea level rise of more than two feet (70 centimeters), which would be enough to devastate coastal communities around the world. But the Thwaites is also acting like a natural dam to the surrounding ice in West Antarctica, and scientists have estimated global sea level could ultimately rise around 10 feet if the Thwaites collapsed.

While it could take hundreds or thousands of years, the ice shelf could disintegrate much sooner, triggering a retreat of the glacier which is both unstable and potentially irreversible.

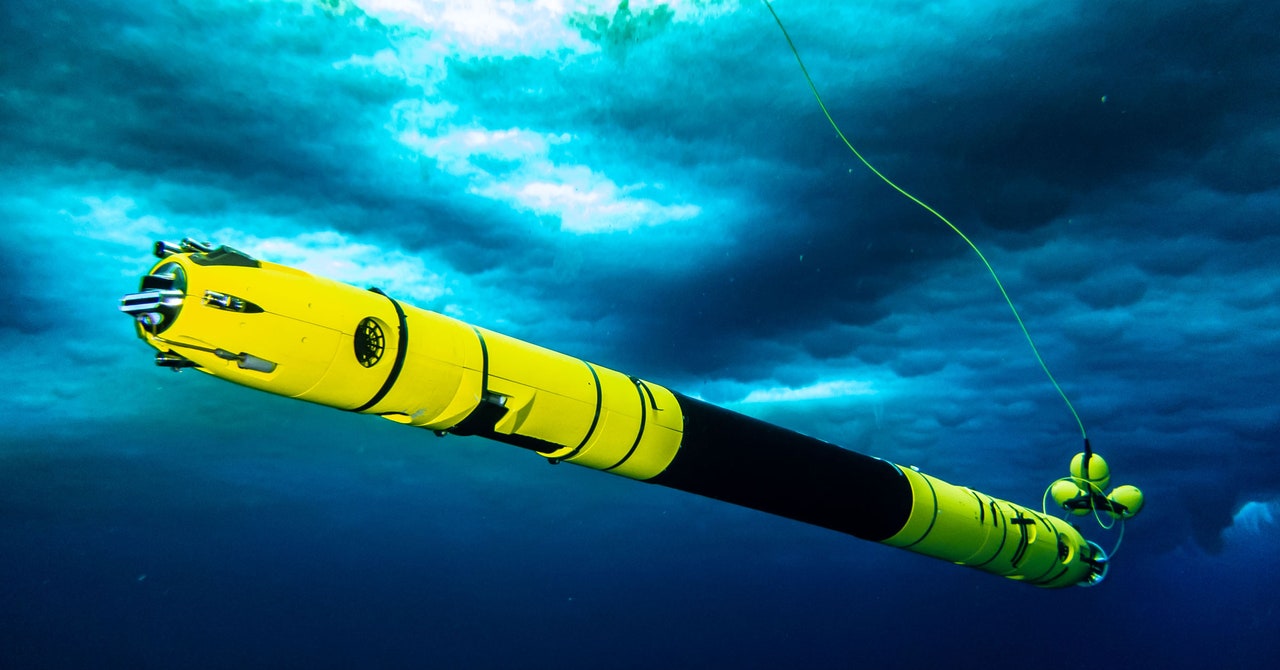

The Doomsday Glacier: Swimming through a borehole, swimming under the ice with a torpedo-like robot

They drilled a hole deep in the ice and then sent down instruments to measure the size of the glacier.

The instruments included a torpedo-like robot called Icefin, which allowed them access to areas previously almost impossible to survey. The remotely-operated vehicle took images and recorded information about the temperature and salinity of the water, as well as ocean currents.

It was able to “swim up to these really dynamic places and take data from the sea floor all the way to the ice,” Britney Schmidt, an associate professor at Cornell University and a lead author on one of the papers, told CNN.

Peter Davis, a lead author on the other paper of the research, told CNN that it shows a very nuanced and complex picture.

“The glacier is still in trouble,” Davis said in a statement, adding, “What we have found is that despite small amounts of melting there is still rapid glacier retreat, so it seems that it doesn’t take a lot to push the glacier out of balance.”

The melt rate was highest in areas under the ice where there were cracks and steep, staircase-like features2. These divert the cold, protective melt water, allowing the heat to reach the ice, and melt it to widen crevasses.

We knew that the glaciers were changing. We knew that there was a correlation between ocean temperature and it. We knew that was happening. We knew that the atmosphere was warm. We were aware that the glaciers were collapsing.

According to Davis, the research can be used to make more accurate projections about sea level rise which can be fed into efforts to mitigate Climate change and protect coastal communities. He hopes it will prompt people to notice the changes occurring and that they will sit up and take notice.

Icefin the robot is designed to go where no human can, swimming off the coast of Antarctica under 2,000 feet of ice. Lowered through a borehole drilled with hot water, the torpedo-shaped machine takes readings and—most strikingly—video of Thwaites Glacier’s vulnerable underbelly. This Florida-sized chunk of ice is also known as the Doomsday Glacier, and for good reason: It’s rapidly deteriorating, and if it collapses, global sea levels could rise over a foot. It could add 10 feet to the rising seas by tuging on surrounding glaciers.

As those features melt, they may be sending shocks through the system. The person says that the Thwaites is falling apart. The whole ice shelf was destabilizing due to rifts and crevasses over the last 30 years. The way that the ocean works into these weak spots makes it worse.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that sea levels will probably rise by between 38 and 77 centimetres by 2100, but the collapse or melting of ice sheets in Greenland and the Antarctic could theoretically contribute an additional metre. Spears is an Earth scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and a co-author of both papers.

Researchers think that grounding-line retreat is driven by warm ocean water melting the underside of the ice. Climate change has shifted wind patterns in the region, allowing a patch of warm water to flow towards the West Antarctic.

The water temperature was about 1.5 degrees above the freezing point. A thin layer of cold, fresh melt water on the ice made it hard for heat to be transferrable to the ice. There is more than enough heat to cause real rapid melting, but you need to get that heat through the protective layer.

The hard-fought observations are critical to refining the treatment of the processes in the models we use to predict the ice sheet’s future, according to Robert DeConto. We need more of them.

The information should be used to make predictions about how Antarctica ice and the global sea levels will change. Whether or not this will paint a frightening picture or a more comforting one is unknown. “I really couldn’t speculate,” says Schmidt.