The Crispr Baby Scientist is back

Developing a Clinical Trial to Study Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in China: The Excited Scientist That Modified Human Embryos for Reproductive Use

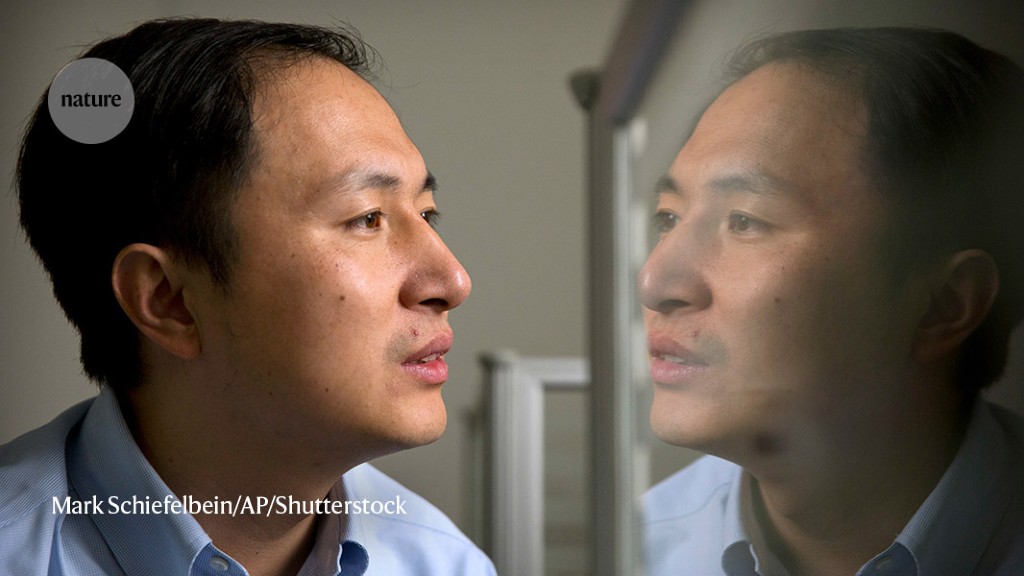

In November 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui shocked the world when he announced, first on YouTube and then at an international scientific gathering in Hong Kong, that he had used Crispr to alter the genetic makeup of human embryos, which were used to establish pregnancies and resulted in the birth of the world’s first gene-edited babies.

Backlash against He was harsh and swift. The scientific community condemned his experiments as unethical and voiced their concerns about the babies health. The Chinese government said he violated medical regulations and they suspended his research. In December 2019, a Chinese court found He guilty of illegal medical practices and sentenced him to three years’ imprisonment. China has since decided not to allow the modification of human embryos for reproductive purposes after hearing about He’s experiment. He was released from prison in April.

He would not say how his lab is being funded, but he said he has hired three workers and will bring on more. On Twitter, he said he hopes to raise 50 million yuan ($7.2 million) and launch a clinical trial for DMD by 2025. And he told WIRED that he wants to make gene therapy more affordable; the few that have been approved in the US and Europe can cost $1 million or more for a one-time dose. “The gene therapies we develop will be offered by a not-for-profit organization, and it is going to be affordable to most families,” He told WIRED, though he didn’t address specifics on how he plans to do that.

The first disease He wants to tackle is Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, a rare and devastating genetic disorder that causes gradual muscle loss and almost exclusively affects boys. He wrote in his email that they were suffering. “I want to help them.”

Why is he going to science, and why should we listen to him? After his release from prison, Kiani traveled to London to meet with He and partner Kirby

But his apparent return to science raises questions about whether researchers who engage in extreme misconduct should be accepted back into the scientific community, and how their subsequent work should be viewed.

“I think he has the persistence and patience to come back to research,” says Samira Kiani, an associate professor of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh and the producer of the new documentary Make People Better, which chronicles the He affair. He didn’t give any on-camera interviews for the film, which instead used recorded phone calls between He and Arizona State University biomedical historian Benjamin Hurlbut, as well as promotional footage shot in 2018 by He’s hired PR team. Since He’s release from prison, Kiani has had a handful of Zoom and email conversations with him. “I think he has some noble intentions, but he’s also a very ambitious person,” she says.

“This meeting has been very disappointing, notably the failure of He Jiankui to answer any questions,” says Robin Lovell-Badge, a developmental biologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London, who attended the event.

“A publicity stunt like today shows he doesn’t have much credibility at least in the eyes of his peers,” says Eben Kirksey, a medical anthropologist at the University of Oxford, UK.

Hours before the event, He wrote a tweet that he was not comfortable discussing his past work. “I feel that I am not ready to talk about my experience in past 3 years,” he tweeted. He also said he would not be going to the University of Oxford for a series of interviews with Kirksey, and that he would not attend an international genome editing summit at the Francis Crick Institute.

Kirksey didn’t comment on whether the Oxford interviews are going well or not, but he did say that he needs to clarify details about his past experiments. In 2018, the world learned that He had used CRISPR–Cas9 to edit a gene known as CCR5, which encodes an HIV co-receptor, with the goal of making the children resistant to the virus. The twins and the baby born to separate parents were conceived through 888-276-5932 888-276-5932 888-276-5932 888-276-5932 888-276-5932 888-276-5932s. The fathers and mothers were both HIV positive and agreed to the treatment.

It is not known whether He’s previous work succeeded or left the children free from side effects. Kirksey is not confident about He’s future scientific plans.

The weekend event was organized by the BioGovernance Commons initiative, monthly online meetings on ethical and regulatory issues between academics in China and thoseacross Europe, North America and Asia, and was hosted by the University of Kent. More than 80 researchers from 13 countries attended virtually, and He, together with some 20 academics and students, were at a venue in Wuhan.

Researchers who attended the talk were not happy. “It bordered on being insulting to the conference organizers and the participants to have used up the time with details and information that were not relevant,” says Françoise Baylis, a bioethicist and professor emerita at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada. Baylis said he gave little to no information about his previous and current work.

Anna Lisa Ahlers, a social scientist and China studies scholar at the Max PlanckInstitut for the History of Science in Berlin, praised He on agreeing to speak to the group but said his presentation fell short of expectations. “From his talk, I would have gotten the impression that he is a salesman.”

Some researchers worry that interest in He Jiankui is diverting attention away from more important ethical issues around heritable genome editing. Will He Jiankui apologize after this event? Is he displaying remorse?,” says Marcy Darnovsky, a public interest advocate on the social implications of human biotechnology at the Center for Genetics and Society in Oakland, California. She thinks that researchers focus on a medical justification for heritable genome editing.