This technology could ruin your life

The case of Imane Jacobsen: A Belgian woman under suspicion in a welfare-frauding system and a far-reaching detection system

Now, two years later, she was under suspicion again. Imane had prepared a number of documents in the days before the meeting, including copies of her Dutch and Moroccan passports and months of bank statements. She went to the library to print them even though there was no printer at home.

Imane came to the Netherlands with her parents when she was a child. She started receiving benefits as an adult, due to health issues, after divorcing her husband. Since then, she has struggled to get by using welfare payments and sporadic cleaning jobs. Imane has chronic back pain that makes it hard to find and keep her job in the welfare system.

She was watching as the investigators worked through the stack of paperwork. One of them, a man, spoke loudly, she says, and she felt ashamed as his accusations echoed outside the thin cubicle walls. They told her that she had brought the wrong statements to the bank and they were going to force her to log in to her account. They suspended her benefits after she refused to submit the correct statements. She was relieved, but also afraid. “The atmosphere at the meetings with the municipality is terrible,” she says. The toll has been taken by the experience. “It took me two years to recover from this. I was destroyed mentally.

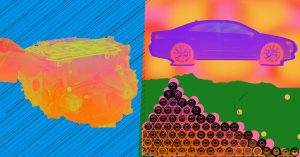

It has become an article of faith among the country’s right-wing politicians that Denmark is losing hundreds of millions of euros to benefits fraud each year. In 2011, KMD, one of Denmark’s largest IT companies, estimated that up to 5 percent of all welfare payments in the country were fraudulent. The Nordic nation would be considered an outlier by the KMD estimates. In France, it’s estimated that fraud amounts to 0.39 percent of all benefits paid. In the Netherlands in 2016 an estimate was made by radio station RTL, which found that the average amount of fraud per benefit payment was 17 dollars. The perception of widespread welfare fraud has empowered Jacobsen to establish one of the most sophisticated and far-reaching fraud detection systems in the world. She tripled the number of state databases her agency can access from 3 to 9 and compiled information on taxes, homes, cars, relationships and employers. Her agency has developed an array of machine learning models to analyze this data and predict who may be cheating the system.

Documents obtained by Lighthouse Reports and WIRED through freedom-of-information requests show how Denmark is building algorithms to profile benefits recipients based on everything from their nationality to whom they may be sleeping next to at night. Technology and political agendas have become entwined, which could have potentially dangerous consequences.

The debate about welfare in Denmark changed in October 2012, when officials asked residents to send in photos of suspected welfare cheats in their local area. The call led some left-leaning commentators to warn of a “war on welfare,” and arrived as the far-right Danish People’s Party—which criticized the government for “luring” immigrants with welfare benefits—rose up in opinion polls.