The Civil Rights Pioneer in Rural Georgia has passed away

A Civil Rights Pioneer, Rev. Charles Sherrod, aka The Meredith March of 1966, the Birth of the Black Power Movement

The Rev. Charles Sherrod, a quietly stalwart civil rights leader who helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1960, became its first field secretary when he took an assignment in rural Albany, Ga., and remained there to create one of the country’s largest and most successful cooperative farms, died on Tuesday at his home there. He was 85.

He was among the first Black leaders to grasp the importance of field work: moving into a community, building ties with local leaders and developing a broad-based coalition of teenagers, college students and church congregations to advance voting rights and desegregation.

Leaving behind a promising academic career, he arrived in Albany in the late summer of 1961. He had just returned from a month in a South Carolina prison where he and three other people were sentenced to hard labor for their role in a sit-in. The four had refused bail, choosing instead to expose the cruelty of a system that punished Black people for the simple act of trying to buy a sandwich.

In the summer of 1966, America’s top civil rights leaders had descended on Mississippi for what became known as the Meredith March. They were making their way from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi to carry on a solo voting rights march begun by James Meredith, the Black activist who had integrated the University of Mississippi three years earlier. Meredith had been shot by a White supremacist and hospitalized with severe bullet wounds.

Despite the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Carmichael recognized that registration alone wouldn’t be enough to protect poor Blacks in the Deep South, where police allowed the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize with impunity. He spent a year organizing Blacks to form an independent political party in Alabama that would provide a platform for poor black people to voice their views on issues of importance to them.

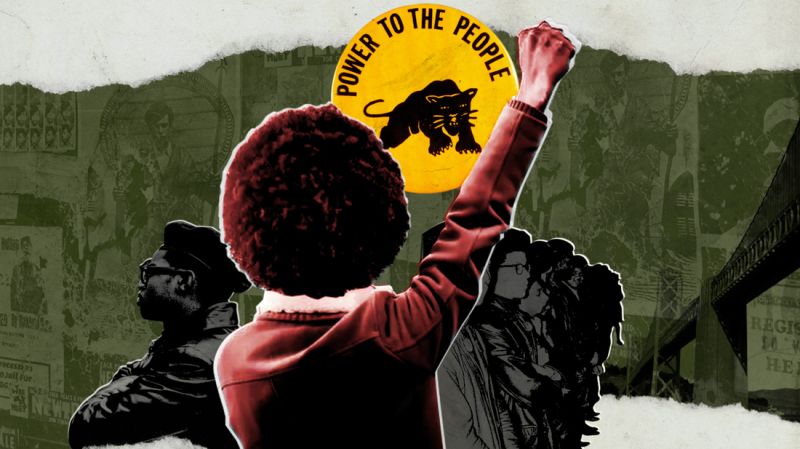

“Black Power!” The crowd shouted back. “We want Black Power!” There were five times when Carmichael cried. “Black Power!” the crowd screamed back each time.

The next day, a short Associated Press story describing the scene was picked up by more than 200 newspapers across America. The Black Power Movement was born in the night.

In 1966, the Black Power pioneers established the principle that all Black lives deserve to matter. A veteran Black journalist who was a student at San Francisco State where Black Studies began remembers that it meant Black empowerment. It seems quaint when you look at it, but the sense of being a poor person was not thought about until you were 25 years old, if you are Black or African American. I guess that’s a testament to the success that Black Power had in terms of making people not feel bad about themselves and to really embrace who they were.”

Oakland, a community where a brutal form of policing by White cops toward the Black populace was the order of the day, was the place where the Panthers came from. The Panther saw themselves as a part of a movement to counter authority. In fact, the official name of the group, which was created by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in 1966, the year before I joined, was The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

The party had a unique mission and structure. The weekly newspaper and the distinctive presence of black leather jackets and berets made the Panthers a visible part of the community. When Black people were stopped by the police, Panthers would gather at the scene in an effort to prevent abuse. If there had been police abuse, the party would help the victim find a lawyer.

King had witnessed a vicious White counterattack in the South, so he attempted to bring his peaceful path to Chicago with a focus on housing. Ronald Reagan was elected to the California state house in 1966 because of a White backlash vote that helped propel a rightward swing in the election two years later.

An ultranationalist faction within SNCC pushed to expel all White members, a bid that was initially dismissed by the group’s leaders but eventually prevailed at a staff retreat rife with drug use in the Catskill Mountains. After only a year as SNCC’s chairman, it was time for a new leader to step in, named H Rap Brown, who was just as inflammatory as the one before him.

Another vicious cycle consumed the Black Panthers. After his release from prison in the late 1960’s, Cleaver collaborated withNewton and Seale to push the Panther’s away from their focus on police and towards talk of armed revolution.

A second lesson is to be prepared for a lot of backlash. In the wake of the last moments of “racial reckoning” in 2020 there was a concerted campaign to demonize “wokeness”, and calls to defund the police.

Whitaker writes that it wasn’t just the language of the civil rights movement that changed in 1966. He says that there was a realization of Black consciousness on a cultural level. “It was really the year when Afros took off, when people started wearing dashikis, where a lot of young Blacks said, ‘We don’t want to be called Negroes anymore.'”

It was also a shift away from integration. The Black people should have a political party and be able to vote for their own officials. A drop in political clout was caused by him expelling the group’s white members. All of this, Whitaker says, laid the foundation for the modern conservative movement — including the election of Ronald Reagan as governor of California in 1966 and George Wallace’s presidential run in 1968.

“A big lesson of 1966 is, beware of the potential backlash,” Whitaker says. I was writing a novel in the middle of all the marches in 2020. I see what happened in 1966 and what happened in 1966 tells me that there is going to be hell to pay. There’s going to be a big backlash to what looks like all this progress in 2020. And sure enough, that’s what we’re living with right now.”

Newsweek is the first national news magazine to be edited by an African American. His previous books include smoketown, my long trip home and the biography of Bill Cosby, which was panned for not addressing accusations that Bill Cosby had drugged and sexually assault women. Whitaker has since acknowledged that it was a mistake to omit the allegations from his book, tweeting, “I was wrong to not deal with the sexual assault charges against Cosby and pursue them more aggressively.”

The story of John Lewis, the nemesis of Mark Luther King and the future of the Black South and the legacy of Dr. Stokely

In terms of integration, what Stokely was saying about the South (vis à vis poor Blacks) and then later the Panthers were saying, even in the North (vis à vis urban Blacks in places like Oakland) … was that actually white people were not interested in integrating with poor Blacks in the South or in the North. The project was to integrate middle-class Blacks with the middle-class white people, but not necessarily the other way around, as it was more about mixing them up with the Black poor in the North.

The press called him Martin Luther King’s nemesis. They got along very well on a personal level. Stokely had a lot of respect for Dr. King. Dr. King didn’t agree necessarily with all of Stokely’s rhetoric, but he admired the fact that he was an activist who had put his life on the line and going out to organize in the South. But there were both sort of differences that had to do with tactics and strategy, but also with background. So one of the things that was different about the Black Power leaders was some of them had come out of the South, but a lot of them came out of the North. They were children of the Great migration. Their parents and grandparents came from the South. Blacks in the South don’t typically have educational opportunities that are similar to what they have in the north. He attended the Bronx High School of Science in New York, an elite high school, and also went to Howard University. The older generation in the South had a tradition of deference that they didn’t have. The previous civil rights generation had a greater attachment to the church. They had a different attitude. They were impatient. They had seen their parents’ dreams dashed when they came north in the Great Migration.

The other effects were on the perception of SNCC by the white world. John Lewis was someone who was deeply respected by white journalists by people who gave money to SNCC. And once they learned that he had been removed, very precipitously, unexpectedly, it immediately sort of cast a shadow over the people who had ousted him. The new leadership group was named after the man, Potter Carmichael. Many of the people who supported John Lewis were suspicious of them.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2023/02/08/1155093955/mark-whitaker-black-panthers-stokely-carmichael-civil-rights-saying-it-loud-1966

The First Four Years of the Panthers: Gayle Fleming’s View on Black Lives, Women’s Rights, and Social Justice

In Watts, after the the Watts riots of 1965 in Los Angeles, there had been a group of local Black activists who had decided that they were going to ride around just looking out for situations where police, white police were interacting with the local Black population and just stand at a remove where the police could see them, but where they weren’t trying to interfere, but just to make their presence known. Like, “We’re watching this. So if anything gets out of hand, if the police in any way abuse their authority, we will be witnesses.”

In addition to being a writer and real estate agent, Gayle Fleming is from Oakland, California. The views in this commentary are her own. CNN has more opinion.

The four years that I was with the panthers were at the height of the protests against the Vietnam war, as well as the early years of the women’s movement. It was a heady time, and I came to realize that my views on social justice and equality had broadened to include those other movements.

Cleaver’s wife Kathleen Neal was met on my first day working for the panthers. The daughter of a career diplomat who dropped out of college in the last year struck up a friendship with me immediately.

I’m not sure if I’d have stayed if Kathleen wasn’t there. She was a college girl like me. In my middle-class Black neighborhood in Oakland, most of the residents were teachers, lawyers, doctors and such.

There was no official membership process for joining the Panthers. If you started showing up at the office regularly, you were considered a member of the Party. When Cleaver asked me to come to the office, he asked me to do many chores, such as answering phones, keeping the office clean and cooking.

The movement was seen as unimportant to the lives of Black women, because most of them were upper-class, college educated White women. The role of Black women was to support Black men, period. I worked on the newspaper in those early days. Women also went to rallies and sold the BPP weekly newspaper and Panther buttons.

The party’s principles leaned that way, even though it never officially declared itself a socialist organization. In order for equality to be possible, people with the most wealth would have to give it up to people with the least.

The free breakfast program was started at the church because of this sense of social justice. A meal before school for the poor was a political act. The success of the program led to it being replicated across the country in government-run programs.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/20/opinions/black-panther-party-black-history-month-fleming-ctpr/index.html

Real Estate Agent: A Career in Real Estate and Its Non-Globe-Hoster-Particular-History-Month-Fleming-Ctpr

I had a child to support, and I was also a single parent. I met and married a man in Aberdeen, Scotland, who was from Britain, and moved with him because he saw poor, underprivileged White people who had been discriminated against. It was eye-opening. When I returned to the US with my daughter she would need to go to college.

I became a real estate agent in my 40s after my marriage ended. Isn’t it the epitome of capitalist greed? Not at all. I pursued a career in reaI estate because I wanted to help people make good choices when purchasing a home — like not buying more house than they needed or could afford. I also used my privilege as a realtor to raise thousands of dollars for the local food shelter, women’s shelter and homeless shelter over the years.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/20/opinions/black-panther-party-black-history-month-fleming-ctpr/index.html

The Curse of History: Black People in the Era of Higher Education and the Pre-Constitutional Left-Right Collision

Black people are still being brutalized and murdered by the police. Institutions of higher learning are still trying to control what Black students learn about their own history. Books are being banned. The planet is collapsing. I no longer serve as a member of Black Panther. The struggle for a more just world goes on for me.