Turkey’s engineers want to know if it’s safe to go home

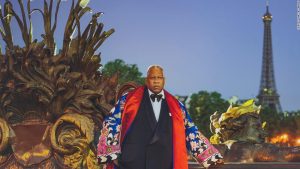

Buildings in Samandag, Turkey, after the Feb. 6 earthquake: A civil engineer’s inspection of a building damaged by the earthquake

The devastating 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Feb. 6 left more than 39,000 people dead and over a million homeless in Turkey alone, where tens of thousands of buildings were destroyed or badly damaged. In Syria, more than 3,600 people died.

The debris of those two buildings, four and six stories tall, litter the street. The building underneath seems to be intact, despite it collapsing on one of the roofs.

The town’s “Great Garden,” normally a verdant green space with benches and shops, is now full of tents, likely to shelter survivors and emergency crews.

Two large high-rise buildings located just south of the park have collapsed. Three more on the northern side of the park have also collapsed.

A significant number of vehicles are seen in the area. Like in other parts of the Nurdagi, some of the buildings that are still standing have a significant amounts of debris surrounding them.

SAMANDAG, Turkey — Yasin Pinarbasi usually works in an office in the Turkish capital Ankara. The civil engineer is working inside the apartment building in Samandag that was damaged by the earthquake.

From the outside the building appears to be in reasonably good condition, but once he enters there’s a cinder block wall that has collapsed on the ground floor. Chunks of plaster and broken tile are strewn across the entryway.

This building has shops at the street level and apartments on the upper floors, just like a lot of other urban buildings in Turkey. Unlike many structures in the area, this one is still standing. The apartments appear from the outside to be intact. But Pinarbasi points out that several support pillars on the ground floor are cracked or completely severed where they connect to the beams above them.

Engineers are being moved through the area of southern Turkey to see if the buildings are safe for people to live in.

Pinarbasi volunteered as one of them, inspecting buildings and reporting initial damage assessments to the government, which he says has to make the final determination of what structures are inhabitable.

The loads would be moved to other columns in the same buildings if one of them were damaged, he says, pointing up at the crumpled concrete where the column connects to the beam. Now they are overstressed.” The stress can cause the remaining columns to collapse. He says they are dangerous.

He opens the app on his phone, uploads a couple of photos of the building and enters estimated square footage and year of construction. Then he said that it was “moderately damaged”.

A restaurant with a large garden serves as a wedding venue on his list. “There are some cracks on the separating walls but not on the beams and columns,” Pinarbasi says, as he and his colleague, Onur Tezcan Okut, survey the building.

But there are no cracks in the plaster walls. Pinarbasi says he doesn’t see any structural damage to the building at all. Kanar, however, insists that if you stand out front, you can see that the building is now tilted. Pinarbasi disagrees, saying if it was leaning there would be evidence in its structural components, particularly at the corners. Kanar is not convinced but continues to walk through the building with Pinarbasi.

There’s been outrage nationwide over the fact that buildings collapsed in the disaster because of substandard construction, sub-par materials and noncompliance with building codes. Some new apartment blocks, that were advertised as being built to the highest earthquake standards, crumpled in the earthquake.

Up the hill from the restaurant, Pinarbasi and Okut move on to a gray four-story apartment building. It is located on a hillside surrounded by olive trees. It’s intact. It has all its windows and there are no visible cracks in the facade.

The sister-in-law of the resident lived on the second floor. The earthquake hit without her husband, so she was alone with her children. She says she gathered her children together and tried to protect them by lying on top of them.

“It’s been really hard emotionally,” Kanar told Pinarbasi as he walked him to the front door. “I have a 2 ½-year-old daughter and when she comes close to the house she starts crying.”

A girl’s perspective on a building damaged by the earthquake of Feb. 6. When she realized she wasn’t going back to her apartment

More than a week after the quake, the apartments inside are in much the same condition as when the family ran out the morning of Feb. 6. There are glass jars on the kitchen floor. The refrigerator and cabinet doors are open. Tables and even a wood stove are overturned.

Now she says she doesn’t ever want to return to her apartment. “I don’t think that I will live here again,” she says as tears well up in her eyes. I have four kids, how can I leave the building? Which one will I pick up?

There is a bigger problem than structural engineering. It’s about fear and a lack of confidence in the construction of buildings.

According to the woman, a small steel frame house with just one story would allow her to live at ground level. She says she even would prefer living in a shipping container rather than go back into the apartment behind her.

The building is marked as not being damaged in the app. With so many buildings damaged across the country, each engineer is trying to inspect 60 per day. They were walking down the hill to the next one.