The trials and successes of sustainable science

Green Science at Work: A Transition During a Medical Career in the 21st Century and the Role of Academic Leaders in Organizations

Nervous and excited. I dedicated myself to the cause of green science, following in the footsteps of my family, friends and colleagues, as I waved goodbye to my successful medical career in early 2023. A few years before this transition, I recognized a huge mismatch between my behaviour at home and my practices at work. I checked all my food wrapping for recyclability at home, and then dumped a lot of single-use plastic in the bin to be incinerated. I was flying all around the world for conferences and had many terabytes of 3D-imaging data stored in the cloud.

The German research foundation DFG has been experimenting with ways to incorporate sustainable practices into grant-application forms. The value of green lab-certification tools also becomes clear: Wellcome will require that grant recipients have achieved a minimum level of accreditation by the end of 2025, and Cancer Research UK includes a silver certification level as an eligibility criterion in one of its grants.

I think that academic leaders in particular — with their decision-making power and role-model function — have a moral obligation to act. A 2023 study4 shows that when leaders in an organization demonstrate responsible and environmentally conscious behaviour, employees are encouraged to do so, too.

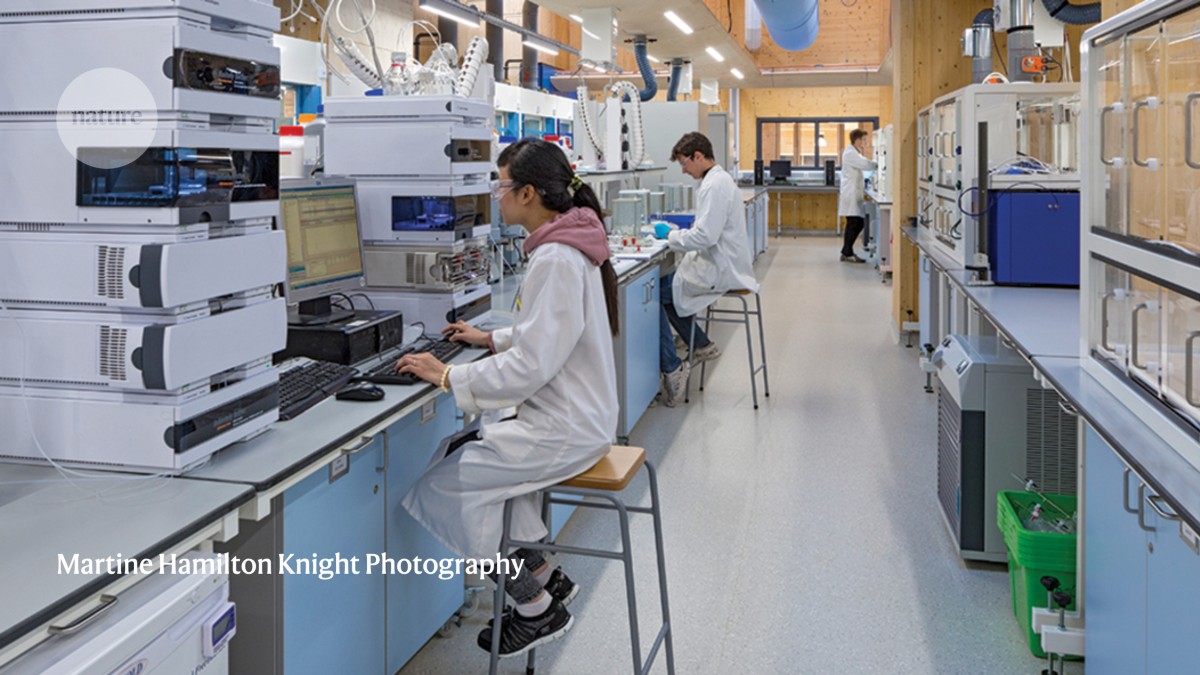

Building a Green Building to Support Scientific Science and the Environmental Impact of the Industrial Revolution: Peter Licence, Director of the Carbon Neutral Laboratory

The carbon neutral laboratory is a one-of-a-kind facility and is saving money despite setbacks. The lab cost a reported $20.8 million and received most of its funding from the pharmaceutical company GSK. The building uses less power than a normal lab of the same size, because it is partly powered by solar and a biofuel heat system. Peter Licence, director of the lab, said that they are paying back carbon used for construction by not buying electricity from the grid. The whole idea is an experiment.

I was inspired by other individuals who shared the same values of climate justice, care and collective action and started to experience feelings of empowerment and hope.

We set up our foundation during the early stage of what feels like a wave of grass-roots initiatives in science and health care. Over the past 3 years, more than 100 green initiatives for health transition have emerged in the Netherlands under the umbrella of the Dutch Green Health Alliance. The wave comes at a time when eco-anxiety, the fear of an environmental cataclysm, is at a high — several surveys have highlighted the distress that negative environmental news is causing1.

Many scientists could reduce their environmental impact by rethinking their approach to planning and executing experiments, Durgan says. It would save money and time as well as energy and resources if they planned more carefully and cut down on redundant tests. Being aware of how you choose to use your experiment and the way you use it is just a good way to do your science.

Scientists should be certain that their results won’t be affected before changing their protocols. “If your research requires you to use 20 litres of solvent or 20 pipette tips, you should absolutely do that,” Freese says. “You should not feel bad about conducting more experiments if it means your results become more significant and reproducible.”

Chemicals that have been part of standard protocols for decades may be used less by scientists at the Carbon Neutral Laboratory. “If a reaction that I want to do requires me to use dichloromethane, I will then challenge myself to look for an alternative,” Licence says.

He says the Carbon Neutral Laboratory has found efficiencies through collaboration. Licence says they share a lot of things. Sharing takes more planning and patience, but helps to save energy and space while promoting conversation and collaboration. The entire building was designed to make people think differently. Students and academics share ideas, work together and often translate knowledge in a much more rapid and much less siloed way than we would have in a traditional old-school chemistry department.”

It will take a while for the lab to live up to its name. The original aspiration was to reach net carbon neutrality in 25 years, enough time so that energy savings can be used to offset the energy required for its construction. “We are, at the moment, slightly behind target because there’s been some technical problems with some of the mechanical, electrical and combined heat and power units that are run on biomass,” Licence says. We will achieve carbon neutrality in 25 years. We are three, four or five years behind the payback schedule at this point.

A 2024 report in the journal RSC Sustainability laid out some eye-opening statistics: at a typical university, research laboratories account for at least 60% of the energy and water use1. And, depending on their field of study, researchers have a work-related carbon footprint that is 7–25 times greater than the per-person climate-maintenance guideline set out in the Paris agreement.

Some steps can be as simple as pushing a few buttons. Durgan explained how the temperature of the 40 ultra-cold freezers was changed up from 80 C to 70 C. Some researchers warned that, if the freezers ever malfunctioned, the samples would spoil faster without that extra 10 °C cushion. To ease those concerns, Durgan spoke to Martin Howes, the sustainable-labs coordinators at the University of Cambridge in the UK, who reported that the scientists there made the adjustment without any issues. There were researchers that reported their own experiences with 70 C freezers to My Green Lab. The Babraham’s energy consumption was reduced by over 20% without affecting the frozen samples.

The hoods are a prime target in energy-conscious efforts. As outlined in the RSC Sustainability report, a typical fume hood uses 3.5 times more energy than an average household does each year1. Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has estimated that it costs more than US$4,500 to run a fume hood per year, a significant dent to a lab’s budget. A simple way to cut the amount of air coming in is by closing the window at the front of the hood while you’re not working. A Harvard initiative in 2015–16 to close fume hoods reduced energy costs by nearly $200,000 each year3.

Durgan warns that other steps aren’t always so obvious or clear-cut. “You might think about trading some plastic items for reusable glassware,” she says. “But that’s going to use water, and it’s going to require energy to sterilize the glass.”

Green Lab: Funding the production of green leaf products to improve a sustainable scientific practice: A case study in Groningen, Ireland

Durgan adds that any cutbacks in the name of sustainability could lead to more waste if the research results aren’t reliable. “The more effort we make to be sure that our data is robust and reproducible, the less collective time and resources are going to be wasted by the international research community trying to chase or follow up those findings,” she says.

Such words might offer comfort to scientists who are concerned about sustainability, but not every product lives up to the billing. A company will often put a green leaf on a product without a verification or proof of concept.

My Green Lab created a database of independently generated environmental impact scores for more than 1,200 lab supplies to improve clarity. The scores, presented on a branded ACT label, take into account the full life cycle of a product, including its manufacturing impact, use of energy and water, packaging and ultimate disposal.

Durgan says funding agencies are the only ones that can bring large-scale change. Funding is going to depend on how sustainable people are, so people who weren’t so focused on the environment will have a reason to be more sustainable.

In a statement to Nature, the NIH Office of Extramural Research said it doesn’t require lab certification, but does “consider the scientific environment during peer review and monitor compliance with all requirements post-award through our grants oversight procedures”.

Cost savings can also be used as incentive. Freese says that at the University of Groningen, the 46 labs that received LEAF certification saw total cost savings of more than $440,000 each year — an average of more than $9,500 per lab — by adopting energy-saving measures that required minimal investment.

The individual labs have reported results that are even better. In 2022, Jane Kilcoyne, a research chemist at the Marine Institute in Galway, Ireland, achieved annual savings of $16,000 by, among other things, turning up the temperature of freezers, closing fume hoods when possible, and ordering and preparing solutions and reagents only as needed (see Nature https://doi.org/nhhm; 2022).