Sickle cell therapies are slowly rolling out

On the cost of gene therapies and stem cell transplants for people with severe Sickle Cell disease: a case study of Maryland woman Teonna Woolford

For now, it’s difficult to tease these risks apart because the clinical trials have been relatively small, and could not include a control group, says James LaBelle, a paediatric oncologist at the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois. It was difficult to know how well the gene therapies would work in people with severe sickle cell disease because participants in clinical trials were not shown to have any history of stroke or organ damage.

In addition to infertility, the chemotherapy can increase the risk of bone degeneration, which is already elevated in people with sickle-cell disease. The chemotherapy regimen can also raise the risk of cancer. DeBaun is hopeful that new transplant protocols that use lower doses of chemotherapy will reduce the chances of these side effects.

Woolford, who lives in a suburb of Baltimore, Maryland, reached out to a few cancer charities that offer assistance to try and retain fertility for women undergoing chemotherapy. “I don’t have cancer, but I’m getting chemo and radiation,” she explained. Could you squeeze me in? The answer was no.

That price was too high for Teonna Woolford, who once dreamed of having six children — before she received a stem-cell transplant at the age of 19. By then, her sickle-cell disease was landing her in hospital about every other week. She had both hips replaced due to bone damage caused by impaired blood flow. Her doctors urged her to consider a stem-cell transplant.

Chemo is required before stem cell transplants and gene therapy can occur. Chemotherapy can take a long time and is risky. Many women that go through it are left infertile. They can opt to have their eggs frozen before treatment, but in the United States, the harvesting, freezing and storage of eggs typically costs more than $10,000.

All of the treatments are expensive: a stem-cell transplant costs between about US$100,000 and $400,000 and the list price of Casgevy, which was developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston, Massachusetts, and CRISPR Therapeutics in Zug, Switzerland, is $2.2 million. These therapies are not accessible for many people with Sickle Cell disease, because of the price tags. People who receive publicly funded health care will be able to receive cell and gene therapies under a plan in the United States. The programme is scheduled to start in 2025, but it is not known how many states will participate. In March, the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence in the United Kingdom asked the developers for additional data after they decided that the treatment is not cost-effective. As a result, Casgevy is not yet available for treating sickle-cell disease through the country’s public health-care system.

gene-targeting therapies have also gotten more advanced. One therapy, called Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel), provides a working version of the gene that is affected in people with the disorder. The other therapy, called Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), uses CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing to reactivate a form of haemoglobin that is normally inactivated soon after birth. This fetal haemoglobin helps to compensate for the dysfunctional version.

How Sickle Cell Disease Changes Peoples Lives: A Support Group Analysis of Victoria Gray, a First Patient in the U.S.

Clogged vessels can also cause strokes and damage organs, particularly the liver, heart and kidneys, over time. In the United States, people with sickle-cell disease have a lower life expectancy than people who don’t have it.

The uncertainties and struggles surrounding the treatments still exist, even though the success stories make headlines. Cells and gene therapies can be as effective as cancer treatments in changing someones psychological, financial and physical health. But, unlike for people with cancer, awareness and support are often lacking for those who have been ‘cured’ of sickle-cell disease, a condition often affecting people from communities that already face discrimination and inequality in access to health care. There is a lack of education among health-care providers on how to manage bone-marrow transplant patients.

So Adekanbi was thrilled when, in late 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first genetic treatments for sickle cell, a disease that disproportionately affects Black people like her and has long been neglected by medical science.

The members of Jones’s support group share stories and experiences, sifting out the misinformation they encounter along the way. In a recent virtual gathering, the group marvelled over Supacell, a drama series on streaming service Netflix in which a group of Black Londoners with sickle-cell disease in their families develop superpowers. They groaned in sympathy when one member recalled their struggles to get physicians to take their condition seriously.

Victoria Gray was the first person in the world to receive the gene-editing treatment, and now it troubles her. NPR broke the news when Gray got treated in 2019.

Many recipients of cell or gene therapy feel like they need to fill the space left by the condition they had spent a lifetime fighting. Krishnamurti said that the disease becomes the narrative. “It’s very difficult to change the narrative of a life.”

Most transplant recipients reported improvements in physical, mental and social health according to the team. Some people struggled with the outcome. Chronic pain and bone degeneration remained a problem for some recipients, as did feelings of isolation4. A lifetime of illness had made the hospital a source of trauma for some. Post-traumatic stress disorder was one of the symptoms that they faced. For others, the hospital was a second home, and they mourned the loss of that community when their health improved, says Dovern.

She was turned away from doctors when she sought help for her pain, because blood tests no longer indicated that she had a disease. She says, “Well, why are you here?” You have to be alone at home.

For most of her life, Genesis Jones’s daily routine revolved around her illness, the painful blood disorder known as sickle-cell disease. Each time she leaves the house, she checks her medication, questioning if she had enough. What was her level of energy? Would she be able to make it through the day?

Less than a month after her transplant, Jones was told she had cancer. Three more rounds of chemotherapy and other treatments drove her cancer into remission, but she still struggles with chronic pain in her back and legs caused by decades of tissue and nerve damage from sickle-cell disease. Her new stem cells make immune cells that are attacking her heart, so she fears that’s caused by signs of mild cardiac inflammation.

Long-term follow-up is a struggle for the wider gene-therapy field, too. Jack Grehan, a videographer in Manchester, UK, was treated for a blood-clotting disorder called haemophilia A more than five years ago. For the first few years after receiving the therapy, he returned to the hospital for follow-up exams each time he was asked to come. But now he lives two hours away from the treatment centre and is juggling childcare and a new job. He has not had a single bleeding episode since receiving the treatment, and he stopped going to check-ups two years ago. He says he will give them more once his life is back to normal.

The data that would address these questions would be collected as the therapies expand from trials to hospitals. Data should be collected from patients for at least 15 years after treatment, according to the FDA. He says researchers outside of the companies are also setting up a database to follow recipients of the therapies.

One of the patients now on that path is DeShawn Chow, 19, of Irvine, Calif. He began treatment at the City of Hope in Los Angeles. He isn’t concerned about the effect treatment will have on his ability to have children and his insurance pays for it.

A lot of people are suffering and even dying each day, says Gray who works full time at a Walmart. “And we have something now that can put a stop to it. I want people to be free of this type of fear, worry and the level of pain that’s indescribable.”

Living in a world where sickle cell gene therapies are available: How many people are willing to pay? What kind of costs does it take to get covered?

More government and private insurers are paying for treatment and care, and the companies are trying to help patients afford it.

We thought the interest level would be low, but we see a lot of traction on par with that. So we’re very encouraged with what we’re seeing,” says Andrew Obenshain, Bluebird Bio’s chief executive officer. “The hospitals are set up and ready to treat. The payors are paying for it. And the patients are interested.”

But getting all the costs covered can be tricky. Although new therapies for these genetic blood disorders are still not available in many places, it’s not clear how many patients will ever get them given that they live in economically disadvantaged countries.

Adekanbi, 29, lives in Boston and says that it’s almost like he is battling himself. I don’t know if you’d call it evil within, but sometimes it feels like that.

Source: Sickle cell gene therapies roll out slowly

A patient with a genetic disorder wondering what to do next to their sickle cell therapies: a case study from the Narrow Stenosimimimetrodefusion Network

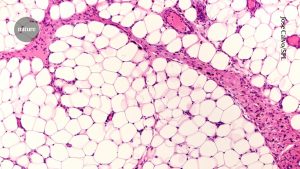

A genetic disorder causes red blood cells to turn sickle-shaped. These cells can cause havoc in the body, damaging vital organs and leaving patients with unpredictable attacks of pain.

She says it gets to the point when you say you can no longer live this way. You feel like you’re losing your mind. Because sometimes I just can’t move. I just lay in one spot and try to distract myself from the pain.”

She is unsure of how she’ll be treated for genetically altered cells in her bone marrow. The symptoms of the disease have been alleviated by modifying those cells. But the chemotherapy would endanger her chances of having kids.

Adekanbi is not the only one wondering what to do. While there’s a lot of excitement about the treatments among sickle cell patients and those suffering from a related disorder known as beta thalassemia, only about 60 of the thousands of patients eligible for the treatment have started the process.

Adekanbi said she would try to freeze some of her eggs if she decided to proceed. But she and other potential patients are concerned about more than their fertility. The treatments are also difficult in other ways.

Source: Sickle cell gene therapies roll out slowly

The Long-Term Effects of Integrated Therapies for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Diseases in the States that You Don’t Live in

“You could be in the hospital for months,” says Melissa Creary, who studies sickle cell at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. “Even if you’re not in the hospital, you’ll have to be nearby the hospital, which could or could not be in the state that you live in. Once therapy is done, there is a lengthy follow-up process in a state that you don’t live in.

And some patients worry about possible long-term risks, according to Dr. Lewis Hsu, chief medical officer of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America.

For their part, Vertex Pharmaceuticals of Boston and Bluebird Bio of Somerville, Mass., which make the treatments, say both therapies appear safe so far.

It is understandable that the treatments are complicated and expensive, and that it is taking time to get them widely accepted.