The WHO may soon end mpox emergency, but there are still outbreaks in Africa

The Ugandan Ebola Outbreak: It’s Not Too Late for the World, Is It Just Happening Too Fast? A Reflection on a World Philanthropic Perspective

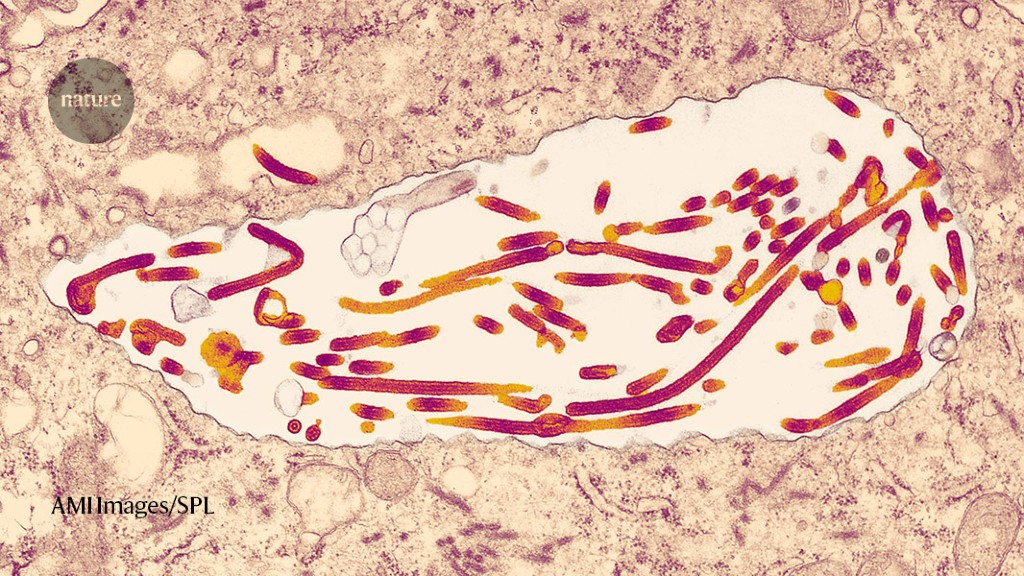

Uganda’s most recent Ebola outbreak should be a wake-up call to the world. Last October, just 3 weeks into the outbreak, the disease spread to Kampala, a well-connected city of 1.5 million people. From there, it might easily have entered other countries.

The vaccine is needed to fight the disease. Wealthier nations must urgently fund mapping efforts and vaccine production to protect vulnerable populations in sub-Saharan Africa and, through them, the rest of the world.

That as many people have died as have recovered is striking, but not surprising. Roughly 50% of people who get sick with the disease will be killed, it’s a very dangerous disease. The fruit bat can be the host of the virus and it can also be used to spread it to other people.

The past president of the Nigerian Academy of Sciences is Tomori. I asked him if he was surprised that high income countries were buying up monkeypox vaccine supplies and WHO was sharing them with 30 non-African countries, leaving the continent without access.

Nonetheless, Tomori rejects the notion that Western philanthropy is the answer. He wants people to not buy the story that Africa is poor. “We’re not poor; it is that we’re not making good use of what we have.”

What will monkeypox do when it comes out of Africa? The role of community-based monitoring in tackling epidemics in the tropics

Because the monkeypox virus continues to cause deaths in Africa and could contribute to future outbreaks everywhere, complacency isn’t an option, Ollario says. He thinks thatMonkeypox may come back in a worse way. The clade I virus was found in Central Africa and researchers worried that it could spread. The strain that is thought to have sparked the global outbreak in West Africa kills 10% of people, and this one is more lethal. Lewis says there have been signs that the clade I strain can spread beyond its usual range, as evidenced by the fact that it was responsible for an outbreak at a refugee camp in Sudan that led to more than 15 confirmed and 180 suspected infections.

Part of the problem is that, of the 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, six of them don’t even have a single medical school while 20 countries only have one. By 2030, WHO estimates that Africa will be short 6.1 million health-care workers, relative to the Sustainable Development Goal threshold of 4.45 health-care workers per 1,000 people.

Perhaps the most infamous example was during the West African Ebola epidemic when it took nearly three months to identify the virus in Guinea. WHO reported that the country took so long because “Clinicians had never managed cases. No laboratory had ever diagnosed a patient specimen. No government has witnessed the social and economic upheaval that can accompany an outbreak of this disease. The virus was already “primed for explosion” after the discovery of the disease.

Mombouli also gives the example of Likouala Prefecture, a swampy area in northern Congo and one of the poorest, least developed regions in the country. He says that Likouala is a paradise for pathogens because of the amount of disease-causingbacteria. Something terrible is going to come out of that area, he says. It’s a matter of time without proper pathogen monitoring.

Public health agencies are still important in helping locals with education and coordinating the response. Indeed, the best early warning system might come from those living on the frontlines of novel diseases. He says that if you take care of the first case you can prevent an epidemic.

Mombouli’s team went to hundreds of villages in the northern Republic of Congo in order to set up a community-based surveillance system for the disease. They educated locals about the virus and how it could spread through infected wildlife carcasses, emphasizing the core message: “Do not touch, move or bury the carcass and contact the surveillance network immediately.”

There is a vaccine being produced in Africa with fill-and-finish plants. In other words, given all the ingredients from Pfizer-BioNTech, these manufacturers fill up vials with vaccine doses and package them for distribution. Mombouli emphasizes that this model is inherently vulnerable since it is only the last step of the value chain, and since Africa currently imports 99% of its vaccines, this is an important step toward domestic production.

In vaccine development, COVID-19 has made a difference. New vaccines are in the pipeline for many diseases. We have an opportunity to capitalize on the latest methods and a sense of urgency. We can’t continue closing the stable door after the horse has bolted. If we keep relying on a market-based model that churns out millions of doses only after an epidemic is under way, then we have already failed.

“Then we would go back to square one if the company decided to leave,” he says. As one concrete example, Johnson & Johnson partner Aspen Pharmacare may soon shut down its South African plant making COVID-19 vaccines because of insufficient demand due to hesitancy and difficulties distributing the vaccine (among other reasons ).

Undoubtedly, this will take time, with Afrigen expected to enter clinical trials later this year and vaccine approval coming in 2024, but much can be done in the interim. African countries can identify other aspects of the value chain, where they can contribute immediately, says Tomori. For instance, one might manufacture glass vials, another rubber stoppers, another testing swabs and so on. Each country doesn’t need to produce everything end-to-end, but Tomori says they should all be starting somewhere instead of patiently waiting for international aid.

Things are beginning to change. A few countries in Africa have exceeded the threshold by less than 10 workers per 1,000.

This policy helps improve the efficiency of the health care system, but doesn’t increase the number of providers. But in 2010, the University of Namibia established the country’s first school of medicine and has since trained hundreds of practicing doctors “who can respond to the healthcare needs of the Namibian people and are advocates for the poor, underserved and marginalised in our society,” according to associate dean Felicia Christians. A call from Namibia’s founding president to invest 50% of the national budget in education and health care emphasizes the country’s steadfast commitment to progress.

While it’s critical to continue building more medical institutions, such as the Kenyan General Electric (GE) Healthcare Skills and Training Institute and the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, there must also be a focus on retention.

While better pay might be the lynchpin, other incentives could include a mix of personal benefits and career improvements: housing, land ownership, modern equipment and pathways for professional growth, according to Kasonde Bowa, dean of Copperbelt University School of Medicine in Zambia. And if the brain drain still persists, Happi thinks that Western countries should start reimbursing the continent for its educational expenses, given that it costs African countries between $21,000 to $59,000 to train one doctor.

This wouldn’t necessarily stop the exportation of health-care workers, but having the West fork over the money could help African countries replenish their workforce. A person should tell the truth if they say that you cannot deplete a continent’s own resources.

It is not to say African-Western partnerships should not be pursued. The laboratory director at the Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Sikhulile Moyo, was the first person to identify the omicron variant. Similarly, Happi collaborates with Broad Institute computational geneticist Pardis Sabeti, and together they deployed COVID-19 tests in hospitals in Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone well before any U.S. hospital had them. The $200 million Paul E. Farmer Scholarship Fund will support students at the University of Global Health Equity in order to “educate future health care leaders in Africa.”

Introducing Simar Sajaj into the conversation: Seven years after COVID-19, the world needs more than just a few locks and quarks

Simar was previously a writer for The Atlantic, TIME, Guardian, Washington Post and more. He studies the history of science and chemistry at Harvard University and is a research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital. He can be followed onTwitter by the nameSimarSBAajaj.

I warned about this problem in a Nature column seven years ago. We have one of the largest chinks in our pandemic-preparedness armour, despite the wake-up call.

The situation is not described as short-sighted. Preparing preventive vaccines for a few million dollars per batch should be seen as a small insurance policy to avoid a repeat of the US$12 trillion the world just spent on COVID-19.

Seven years from now, I don’t think I’ll be writing this again, what will it take to finally catalyse change? We have come a long way from not speaking about this issue at all, to now being able to point to its relevance daily. There is a change in mindset in sight according to me.

Wealthy countries should take the lead. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) should be fully funded to do this work so that they can collaborate with government research agencies.

We need a better way. In order to fight COVID-19 the world needed more than just a few locks, quarks and contact tracing. When rich countries are affected by a fatal infectious disease, there is a massive global effort to develop vaccines and therapeutics.

If you have a family that needs 21 days of income to survive, or if you have been exposed to the disease in your own family, it’s difficult to separate them from one another in an isolation facility for 21 days. We had to impose a 63 days of lockup in two rural districts, with a combined population of nearly one million.

The effect on people’s livelihoods and on the local timber industry was devastating. The societal disruptions that these interventions bring fuel people’s anger and distrust of public-health efforts. They are just one way to curb the spread of the disease.

Testing human blood for the disease was one of three techniques that would be combined for mapping. For human blood samples, there is a cheap, easy way to get started: testing stored samples from nationwide HIV surveys, which many of these countries already have. Uganda has an HIV survey. If we used the results from the testing of these samples for the new surveys we would be targeting specific areas. But African nations will need support: funding for reagents, and expertise in serosurvey design and disease modelling.

A full picture of the longevity of vaccine-induced immunity is unknown for Ebola, but existing evidence is relatively encouraging (Z. A. Bornholdt and S. B. Bradfute Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 699–700; 2018). Antibody levels in the blood decrease over six months to one year, but how long T-cell immunity lasts is unknown. There is still much data to be found, but an annual vaccine could be possible.

And the global interest has inspired some research projects in Africa. Rosemary Audu, a top researcher at the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research in Lagos, and her colleagues created the country’s first mpox test for research use. Audu and her colleagues got the CAN$3 million (US$2.25 million) grant from Canada’s International Development Research Centre and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which she hopes to use to understand the virus’s transmission and spread. As part of this project, she plans to apply her team’s mpox test to samples stored at clinics around the country that treat sexually transmitted infections, to look for undiagnosed cases.

A lot of the virus has been spread outside of Africa by men who have sex with men. Transmission patterns and clinical manifestations of the disease are much harder to pin down in some African countries, where rodent species are thought to naturally harbour the virus and regularly spread it to humans. For example, whereas more than 95% of people infected with the virus in the United States have been men, only about 60% of those who have had confirmed infections in Nigeria are men.

Still, the global focus on the virus has changed a few things in Africa. According to Ogoina, physicians who have never heard of the disease now know what the telltale signs are because of the published case reports.

Researchers at the meeting said there was evidence pointing to the effectiveness of any vaccine. A vaccine trial in Equatorial Guinea could also provide valuable data on the safety of vaccines and the immune response they generate in populations at risk of future outbreaks.

At this week’s WHO meeting, officials discussed the practicalities of testing a Marburg Virus vaccine in West Africa. All the leading contenders are viral-vector vaccines, similar to the COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, UK.

“I cannot emphasize enough the need for speed,” said John Edmunds, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, at the WHO meeting.

Are vaccines available in the Kie-Ntem province? An independent panel of WHO experts could determine the outcome of vaccine trials in Equatorial Guinea

The Kié-Ntem province is situated in the north of the country, on the border with other countries. It has been linked to 9 deaths among 25 suspected cases, with the first known case dating to early January. The larger of the Marburg outbreaks has already been detected, according to Nature. Breakes are usually small and finish quickly after the effective interventions have been put in place.

The exceptions are a 1998–2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that was linked to 154 cases and 128 deaths, and a 2004–05 epidemic in Angola that caused 227 deaths among 252 reported cases.

The Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington DC has a candidate vaccine that uses a modified chimpanzee adenovirus to deliver instructions for cells to make a Marburg virus protein, whereas a candidate made by Janssen in Beerse, Belgium, uses the human adenovirus on which the company’s successful COVID-19 vaccine was based (Janssen is a subsidiary of Johnson and Johnson).

Candidates from Public Health Vaccines (PHV) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the International Aids Vaccine Initiative (IAIVI) in New York City and Auro Vaccines in Pearl River, New York, are based on weakened forms of vesicular stomatitis virus — the vector that is used in the first approved Ebola vaccine.

If a vaccine trial in Equatorial Guinea were to go ahead, an independent group of experts that advises the WHO would make decisions about which vaccines to test, says Anna Maria Henao Restrapo, who co-leads the WHO’s R&D Blueprint effort to lay the groundwork for such studies during outbreaks. Any trial would have to be approved by the government of Equatorial Guinea.