Famed Pacific island’s population is not real

Drosophila melanogaster: The minuscule parasitoid wasp discovered in a Rapa Nui fruit fly

In the 2006 book Collapse,Jared Diamond wrote of a theory that said the inhabitants of Rapa Nui ravaged the island’s environment and caused it to crash prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Despite being a hugely studied model organism, it seems that there’s still more to find out about the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, as researchers have discovered a new species of parasitoid wasp that infects the species. Unlike other parasitic wasps, this one lays its eggs in adult flies, with the developing larva devouring its host from the inside. The minuscule wasp was discovered by chance in an infected fruit fly collected in a Mississippi backyard and analysis suggests that despite having never been previously identified, it is widespread across parts of North America.

A dye that helps to give Doritos their orange hue can be used to turn mouse tissues transparent and engage with climate-science sceptics.

Never miss an episode. Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on

Apple Podcasts

,

Spotify

,

YouTube Music

or your favourite podcast app. You can find an RSS feed for the NaturePodcast.

Evolutionary genetics of the Rapanui Island – the last nail in the coffin of this collapse narrative? Revised contributions by Nägele and Malaspinas

The latest analysis, published on 11 September in Nature1, “serves as the final nail in the coffin of this collapse narrative”, says Kathrin Nägele, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Correcting the image of Indigenous people is what it’s about.

Community outreach in Rapa Nui shaped the questions the project tackled, says Malaspinas, such as trying to settle the relationship between ancient and present-day Rapanui. There was also a strong interest in repatriating the remains, something the researchers hope will eventually happen.

After settling Rapa Nui by around ad 1200, ancient Polynesian people developed a flourishing culture famous for its hundreds of colossal stone statues, called moai.

When Europeans first reached the island in 1722, they estimated that it had a population of between 1,500 and 3,000 people and found a landscape denuded of the palm-tree forests that would have once covered the island. By the late nineteenth century, the Indigenous population, called the Rapanui, had dwindled to 110 people, owing to a smallpox outbreak and the kidnap of one-third of the inhabitants by Peruvian slave traders.

The theory that a pre-contact population of over 15,000 plundered the island’s resources, as well as large estimates for the population, is being challenged by researchers.

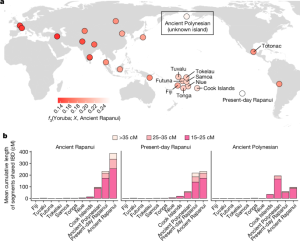

Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, a population geneticist at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and Víctor Moreno-Mayar, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Copenhagen, were hopeful that ancient Rapanui DNA could address the ecocide theory, as well as another lingering question: when ancient islanders mixed with Native Americans.

Information about how a population has changed over time can be found in the ancient and modern genomes. When there’s a small population, segments of the genes shared between people tend to be longer and more plentiful than when there’s a lot.

It’s not easy to translate these trajectory into actual population numbers, but further modelling suggests that the genetic data aren’t consistent with a drop of up to 3000 people before the eighteenth century. “There’s no strong collapse,” says Malaspinas. We are quite confident that it didn’t happen.

According to Keolu Fox, a genome scientist at the University of California, San Diego, the finding that Rapanui reached the Americas will come as no surprise to Polynesian people. He says they are confirmation of something they already knew. “Do you think that a community that found things like Hawaii or Tahiti would miss a whole continent?”

The researchers received the same reaction when they presented their initial findings. Malaspinas recalls being told that ‘of course we went to the Americas’. She, Moreno- Mayar, and other colleagues went to the island often to talk to officials and residents.

Nägele, who works in Polynesia, thinks the researchers did a good job of engaging with people in Rapa Nui. She believes that scientists have a stronger role in returning Indigenous remains to their place of origin.