Live music is not a good thing but could be a catalyst for change

‘The Guitar’ as a Background Track for a Popstar Revival of Dolly Parton’s “I Know She Laughs”

It is like a therapy session and you have to think about how to phrase it. I’d say — worry less and be bold. Your ideas are worth sharing and it’s fine if people don’t like them. Reach out to people to see if they want to collaborate with you. You have to make yourself known if they are going to say no.

I play the guitar well enough to sing along with it. Chris Jones, the climate researcher at the Tyndall centre, says that McLachlan does a particularly good rendition of Dolly Parton’s song.

Australian pop superstar Kylie Minogue at Glastonbury Festival in Somerset, UK, at her comeback show after she’d been unwell. I thought she was incredible.

A Road Map to Kickstart Change: Mark Donne, The Smile, The Tyndall Centre, and the Plan to Kick-start Change

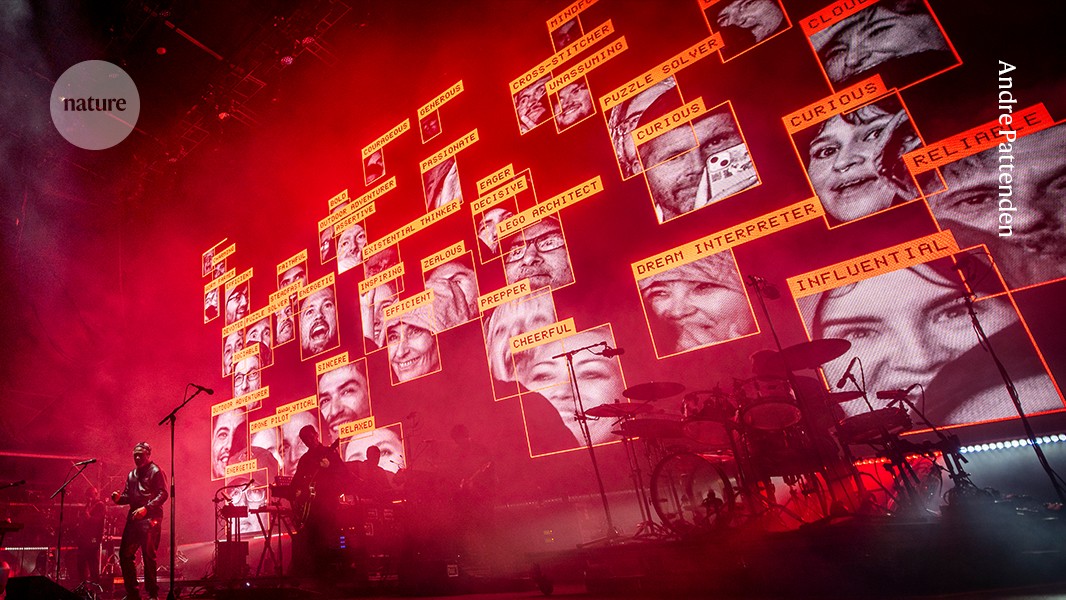

Mark Donne, producer with Massive Attack, called the singer in 2019. The band has pushed boundaries in music for 25 years, and their blend of hip-hop and electronica has earned them a BRIT award. Donne was wondering if McLachlan, the section of the Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research located at the University of Manchester, UK, would assess the carbon footprint of Massive Attack and create an action plan to kick-start change.

“I look at it from the angle of, what is the world that we are trying to protect?” McLachlan says so. I believe live music is a beautiful aspect of being human.

The Act 1.5 team is in talks with British rock band The group of band members formed The Smile to apply some of the road map to their tour activities. The Tyndall Centre has influenced and inspired REVERB, an organization in Portland that helps artists such as David Matthews Band to reduce their tours’ environmental impact.

The commitment Massive Attack has made to help produce the road map and then test its effectiveness is exactly what McLachlan looks for in a collaboration. She appreciates the band’s desire to challenge the status quo: they are “people who don’t want you to write them a report that sits on a shelf, but they really want to have a go at making change”, she says.

Donne says more work needs to be done to scale up the changes made at Act 1.5 to make them practical for other artists and events. For example, because diesel generators are cheaper and ubiquitous in the industry, there was an extra cost to not using them — shared in this case by the band and the battery providers. “Central governments need to step up and do more to incentivize decarbonization,” says Donne.

Understanding carbon budgets to help governments and the public understand what you don’t know about the world, but how you can use it to inform future councils: a case study of Massive Attack

McLachlan thinks that acknowledging things you don’t know is crucial in an effective collaboration. “You have to be willing to say that you don’t understand. When you do this, you start to learn to speak in a way that more people can understand you and where you’re coming from.”

McLachlan says that since 2019, more than 250 councils have used the carbon-budget tool created through the GMCA project to set or inform their own targets. “It’s not a silver bullet, but I do feel proud that we made the tool freely available,” says McLachlan. She says that it has helped people to think a bit more about near-term emissions reductions rather than the 2050 framing of reductions. McLachlan has a skill at helping people understand complex research into actionable insights according to Mark Atherton, the director of environment at the GMCA.

In 2003 she joined the Tyndall Centre as a research assistant and in 2005 she started a PhD in controversy studies of renewable energy projects. She was drawn to the centre’s interdisciplinary environment and working directly with businesses and industries, and, after a brief stint in industry, she rejoined the centre as a knowledge-exchange fellow. McLachlan enjoyed the challenge and pace of the work. She says you are running from one contract to another. “I found that really exciting.”

She was attracted to the project’s scope. “It’s an area that you might think is quite hard to decarbonize — artists flying around the world taking loads of stuff with them — how are you going to get carbon out of that? If you can demonstrate how to do it in a difficult sector like this, then couple that with the reach of Massive Attack — it can be powerful.”

McLachlan said the band was aware that they would give it to them straight and not sugar-coat it. She says of her team that they are a critical friend but in a jolly packet.

Donne, who is now lead producer of Act 1.5, says that McLachlan was recommended to the band by one of her former colleagues, Alice Bell, who is head of policy in climate and health at Wellcome, a charitable funding organization in London. Massive Attack “wanted to set a clear standard to adhere to that was Paris 1.5 compatible”, says Donne. He says that most other schemes in the sector didn’t meet that standard. The team needed scientists and analysts to make sure the work they built their own projects on was credible. Donne says that McLachlan “is a joy to work with: always clear, always analytical, always frank”. He appreciates the social-science component of the project. “McLachlan and [road map co-author Chris] Jones are very good at looking at knock-on effects and the possible negatives” of initiatives that the band considers, he says.

Source: Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Train Hugger – Reducing the Impact of a Large Battery Distribution on the Environment and Climate of the UK music event. The case of the “UK Music Event”

Some train travellers who booked through the train Hugger app were given incentives to decrease their carbon footprint. There are free bus transfers from the city’s two main stations to the event, and access to a Train Hugger guest bar which includes separate toilets for people who are not from Bristol. The event had a zero waste-to-landfill policy with all the food being plant based and provided by local suppliers.

The entire concert was powered by batteries, renewable energy, and low-energy lights. The batteries were moved on site with the help of electric trucks. The UK music event used one of the largest batteries ever provided for a music event. This saved about 2000 litres of diesel, and resulted in a reduction of 5,340 grams of carbon emissions.

“If you suggest something, and people say, ‘Well that would never happen,’ but then they can see it already has happened, it just unlocks a totally different way of thinking,” McLachlan says.

Sustainability in the music industry: the Taylor Swift Eras Tour, a record-breaking 25 years in 2023, is one way to turn it up

The Taylor Swift Eras Tour consists of over 150 shows across 5 continents in 21 months. In 2010, researchers used figures from 2007 to estimate that the UK music industry produced some 540,000 tonnes of greenhouse-gas emissions annually, around 0.1% of the country’s total energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. It was live music that accounted for most of it. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 014. The figures might have gone up.

Efforts like that are needed. Live performances are an increasingly important source of revenue for artists, and audiences love them, too: the multinational company Live Nation Entertainment reports that more than 145 million fans attended its over 50,000 events worldwide in 2023, a record. For every one, temporary sets must be constructed, venues supplied with energy, and performers, equipment and audiences transported, often over large distances.

Powered by the enthusiasm of fans, many stars are emphasizing sustainability in their tours and live events. The industry needs to turn it up to eleven.