Is there still an edge in innovation for South Korea?

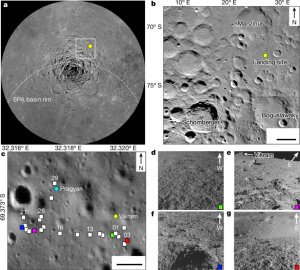

South Korea’s contribution to the European Union’s research funding for basic science: a case study in the nano-scale scanning tunnelling microscope (QNS) facility

The Director of Operations at the Center forQuantumnanoscience, Michelle Randall, is showing off the facilities. “This is where we isolate our scanning tunnelling microscopes (STM) from any vibrations,” she says, pointing to an 80-tonne concrete damper, a mechanism that reduces interfering movements to near zero. A year ago, researchers at QNS formed a device based on single atoms that allowed multiple qubits to be controlled at the same time. Science 382, 87–92; 2023). The work, done by QNS in collaboration with colleagues in Japan, Spain and the United States, could have applications in quantum computing, sensing and communication.

The diversity of teams that populate its labs gives QNS an edge, says Randall. Our composition is 50:50 and we’re English-speaking as a result. She points to a room with four women: two South Koreans, one French and one Iranian, and they are all examples of the collaborative spirit.

South Korea has become the first Asian country to join the European Union’s biggest research-funding scheme because of policy shifts. Announced in March, the new partnership will drive collaborations between South Korean and European researchers in areas such as quantum technologies, semiconductors and next-generation wireless networks. South Korea is also forging bilateral cooperation agreements across Europe, such as with Denmark on clean-energy technologies and Germany on basic sciences, including the launch of a joint centre with the Max Planck Society, Germany’s flagship basic-research organization, at Yonsei University in Seoul.

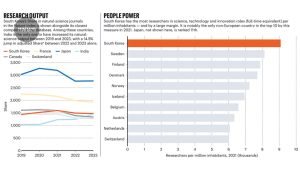

Recent policy changes have exacerbated this problem. In 2023, the South Korean government announced a cut to R&D funding by 16.7%, later winding it back to 14.7% after a widespread criticism. The amount of spending on R&D is more than 3% of GDP, far above the average of 2.5%, and some targeted cuts to certain programmes is probably a good idea. Young researchers have a disproportionate impact on the cut to basic funding because they come from the professor’s own funding.

Taking on more joint projects with Europe could help to diversify South Korea’s internationally collaborative outputs in the Nature Index. The United States is the main research partner of South Korea, with a collaborative Share that is measured by their output of natural-sciences research. The second strongest partnership in South Korea is formed by China with a collaborative Share of 300.41 followed by Japan.

In order to minimize its exposure to any supply-chain disruptions or political risks associated with ongoing US–China tensions, South Korea must look farther afield when establishing research links, says Lee Myung-hwa, who studies policy and innovation at the Science and Technology Policy Institute think tank, in Sejong. She says building trust with collaboration partners is the key to keeping them stable and unaffected by policy directions.

Cha points out that southeast Asia has long been of strategic and diplomatic interest to South Korea, and it has the potential for joint innovation projects. “For instance, in Indonesia, there’s no governmental institution in charge of AI,” she says, which could open up the possibility of future collaborations around ethical and strategic development of AI technologies.

There are many social and cultural considerations that can be taken into account when promoting high-risk, high-return research. South Korea has the world’s lowest birth rate, which is putting increasing strain on the health-care system. When science, technology and innovation were the government’s focus, the top students went to disciplines such as engineering. Nowadays, they pursue medicine, because it’s a secure, well-paid and prestigious career with strong government support. In February, the government increased the national medical school intake quota to 5,058 from 3,058, which has been the same number over the last six years. Increasing the quota will cause the science and technology students to go to medical school first, says So Young Kim. Even at SNU, the leading South Korean institution in the Nature Index, “their engineering programmes have a hard time recruiting students from their own undergraduate programmes”, she says.

Religious and cultural differences also pose difficulties. A student at the University of Daegu, who left Pakistan to pursue a PhD in computer science, is involved in a construction project near his university that has angered people in the local community. Many Muslims in South Korea have told Razaq that they are humiliated by their peers over food choices and lack designated areas to cleanse their body before prayers.

The role of cultural attitudes in engineering innovation in South Korea: a case study of the Brain Pool program, MSIT and a Korean company

The Brain Pool program which gives PhDs access to 300 million won a year for three years and the Brain Pool Plus which gives outstanding researchers 600 million won a year for 10 years, are examples of government-funded initiatives. MSIT also plans to introduce support programmes to help new arrivals settle in and build networks.

The company that develops artificial intelligence for self-drive and traffic management was mandated to have an English-language work environment to attract international talent. Such a culture is unusual in South Korea; although many companies have English-speaking requirements, these are often not enforced, says Evan Thomas, business development manager at Seoul Robotics. “The ability to communicate in English without constant translation and cultural interpretation has been a significant advantage compared to more traditional South Korean companies,” he says.

Thomas says that cultural attitudes can affect long-term retention. “Many South Koreans view foreigners as temporary visitors rather than potential long-term residents, discouraging them from settling in,” he says. A 2023 survey by the Korea Institute of Public Administration, a government-sponsored research institute in Seoul, seems to back this up, reporting that less than half of the respondents say they accept foreign nationals as members of South Korean society.

A student from Vietnam, Hong Bui, accepted a position at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich in March after finishing her PhD at QNS. The limited permanent career opportunities that can be had by international researchers in South Korea is one of the reasons that she wants to leave, despite having enjoyed her time there. Many South Korean companies value overseas experience more than domestic experience, she says.

If it wants to regain the lead in technical innovation, South Korea will have to work hard, but its history of pivoting in response to dramatic changes will make it stand out. “It’s a question of understanding what needs to be done, and then having the right leadership to implement the change.”

To achieve growth in telecommunications, buy-in from the corporate sector was crucial. State projects gave companies the potential to completely dominate an industry, which was a key incentive for them. A few companies that were originally food and construction firms were catapulted into some of the world’s most successful conglomerates thanks to the strategy. But funds were never given freely. “The government would attach monitorable performance outcomes, and the president would sit in on meetings and stipulate targets for companies,” says Sung-Young Kim. During South Korea’s period of military rule, from 1961 to 1993, repercussions for missed targets ranged from being cut from further funding to jail time imposed for company bosses whose performance lagged.

The creation of tailored programmes for funding science with the possibility to be paradigm-changing was a recommendation from theOECD innovation review. “Of the many people we interviewed, many understood the need to support more high-risk, high-return research, and some in positions of influence were starting to work on it,” says Hemmert. But the level of change required has not been fully appreciated, he adds. South Korea’s leading universities have a high level of regulation. The government has designated some as ‘research universities’ — including Seoul National University (SNU) and KAIST — that receive more funds, “but instead of just leaving these well-resourced institutions alone to set strategies, there are still a lot of rules”, says Hemmert.

Regardless of the work being funded, a more fundamental issue that is stifling innovation in research is the short-term nature of funding. “Our funding programmes are usually very short, typically one or three years,” says So Young Kim. Mid-term performance milestones are set and a heavy emphasis is placed on measuring output in terms of top-tier journal publications and patent registrations, she adds. “If you are not successful in the current programme, there’s no way to continue your research, because new funding is based on past records.” The funding structure makes it hard to focus on quick wins.

Hemmert says that for cutting-edge research, you need a more patient approach. He adds that research in Japan — where the same topic can be pursued for decades in multi-generational labs — offers an interesting point of reference. South Korea has no scientists with a good number of prize wins. “When I looked at the profiles of Japanese Nobel scientists, they typically worked on some specific scientific problem for decades.”

Hemmert says there is room for improvement, even though the country’s research universities often rank highly in industry–academia linkage metrics. “They understand the need to collaborate more, yet when it comes to implementation, it’s still a bit chequered.”

The government is considering other options for encouraging young people into science, such as expanding a programme that allows men to serve out their 18–21-month-long mandatory military service by continuing to work in their university labs. “The bigger challenge, I think, is not how we design these extra benefits, but how we make studying science and technology a really fulfilling experience for those who are interested in it,” says So Young Kim. She says that students and early career researchers often feel as though they are stuck doing manual labour in the lab, rather than being taught how to conduct research, which can be very unrewarding. “We need to find that intrinsic motivation for our students. Professors should become role models so they can show that we live a meaningful life through this career.