Is the election in India influenced by misinformation?

Generative Artificial Intelligence Can Level the Playfield: Understanding the Importance of AI-Generated Content in the Indian Context

Brilliance artificial-intelligence applications that help reduce the barrier to producing dubious content are another reason to tackle the issue. As Kiran Garimella at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and Simon Chauchard at University Carlos III in Madrid point out in a Comment article7, their studies of users of the WhatsApp messaging app in India indicate that generative AI content does not seem to be prevalent in the misinformation mix as yet — but from what we know about how the use of technology evolves, it seems likely that it is only a matter of time.

Can genAI level the playing field? GenAI has the potential to disrupt existing power dynamics in content production. By democratizing content creation, it challenges the dominance of well-resourced political parties.

Monitoring of this technology’s prevalence and impact in different contexts will be important as it continues to evolve. In the Indian context, researchers need to look at more details about the impact of AI on society and politics.

Vulnerable digital privacy and security can’t be sacrificed to target misinformation, which is counter-productive. End-to-end encryption on platforms such as WhatsApp should not be undermined.

Collaboratively evolving new regulatory frameworks, involving governments, the technology industry and academic bodies, can ensure that standards keep pace with AI advancements. The importance of support for research to build sophisticated technologies that can detect artificial intelligence is crucial in the age of synthetic media.

Policymakers should thus develop comprehensive global and domestic strategies to combat the ill effects of AI-generated content. Public messaging to stress the importance of source verification is key. It’s important to build a framework to make sure that content is watermarked. Initiating public awareness campaigns to educate communities, especially inexperienced tech users, about the nuances of AI-generated content is also important.

It is important to note that misinformation can easily be created through low-tech means, such as by misattributing an old, out-of-context image to a current event, or through the use of off-the-shelf photo-editing software. The nature of misinformation might not change much with the help of Genai.

Over the past 12 months, several high-profile examples of deepfakes produced by genAI have emerged. These include images of US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump in the company of a group of African American supporters, an audio recording of a Slovakian politician claiming to have rigged an upcoming election and a depiction of an explosion outside the US Department of Defense’s Pentagon building.

We have been studying how political parties are using the platform to spread misinformation, for over five years. In India, we have collected data from app users through a privacy-preserving, opt-in method.

We were especially interested in content that spread virally on WhatsApp — marked by the app as ‘forwarded many times’. Such a tag is placed on content that is forwarded through a chain that involves at least five hops from the original sender. Five hops could mean that the message has already been distributed to a very large number of users, although WhatsApp does not disclose the exact number.

Genai Technology and the Rise and Fall of Religion: Confronting Digital Media and Culture with Past, Future and Future Directions in the Industrialization of India

Projections of a brand of Hindu supremacy is one of the themes seen in the Genai content. We discovered videos that showed Hindu saints making offensive statements against Muslims and referencing historical grievances. AI was also used to create images glorifying Hindu deities and men with exaggerated physiques sporting Hindu symbols — continuing a long-standing and well-documented propaganda tactic of promoting Hindu dominance in India. We also found media depicting fabricated scenes from the ongoing war in Gaza, subtly equating the 7 October 2023 attacks by Hamas against Israel with alleged violence perpetrated by Muslims against Hindus in India. Using current events to target minority groups is a well-documented trend in the Indian social and political context5.

Our first findings show the power of GenAI to make culturally resonant visuals and narratives, beyond what conventional content creators can achieve.

One category of misleading content we identified relates to infrastructure projects. A new train station that was said to depict the birth of the god Lord Ram spread widely in a visually plausible way. The pictures featured a spotless station showcasing depictions of Lord Ram on its walls. Ayodhya has been the site of religious tensions, particularly since Hindu nationalists demolished a mosque in December 1992 so that they could build a temple over its ruins.

The cases we document show that the potential for personalization can be seen in the future with the use of Genai technology. The hyper-idealized imagery is very appealing to viewers who already have sympathetic beliefs and can still be highly effective. This emotional engagement and visual credibility that is provided by modern Artificial Intelligence could allow such content to be persuasive.

The first step to tackling misinformation must be for companies to engage more with researchers. It is possible for people to ethically work on data and ensure people’s privacy. Moreover, taking steps against the spread of provable falsehoods does not amount to a curb on freedom of speech if it is done transparently. If companies don’t want to share data, regulators should force them to.

Funding is a part of the misinformation industry that is less well-known. Misinformation wasn’t created by the Internet or social media, but the advert-funded model of much of the web has boosted its production. For instance, if people look at and click on ads on misinformation sites, the sites get a cut of the ad space auctioned off to companies.

The Holocaust happened. COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives. There was no widespread fraud in the 2020 US presidential election.” These are three statements of indisputable fact. Indisputable, and yet, in some parts of the internet.

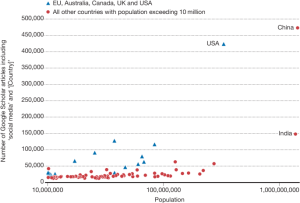

One of the articles in Nature devoted to online misinformation was written by Ullrich Ecker and his colleagues at the University of Western Australia in Perth. This is a good time to talk about it. With more than 60% of the world’s population now online, false and misleading information is spreading more easily than ever, with consequences such as increased vaccine hesitancy2 and greater political polarization3. In a year when countries with more than one billion people are holding major elections, there is a heightened sensitivity to misinformation.

The period included an attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, which led to the deplatform of tens of thousands of users. The authors show that the sharing of misinformation went down after the move. It is not clear whether the ban changed user behaviour or whether the Capitol violence had an effect on the number of people sharing stories about the presidential election. Either way, the team writes, the circumstances constituted a natural experiment that shows how misinformation can be countered by social-media platforms enforcing their terms of use.

It looks like the experiments will probably not be repeated. Lazer told Nature that he and his colleagues were lucky to collect data before and during the attack, and at a time when it was easy for scientists to get data from the social media platform. Since its takeover by entrepreneur Elon Musk, the platform, now rebranded X, has not only reduced content moderation and enforcement, but also limited researchers’ access to its data.