The Sun may be blotting Europe’s space agency out

Proba-2: Exploring the Sun’s Wispy Outer Atmosphere with High-Resolution Imaging and Imaging Detectors

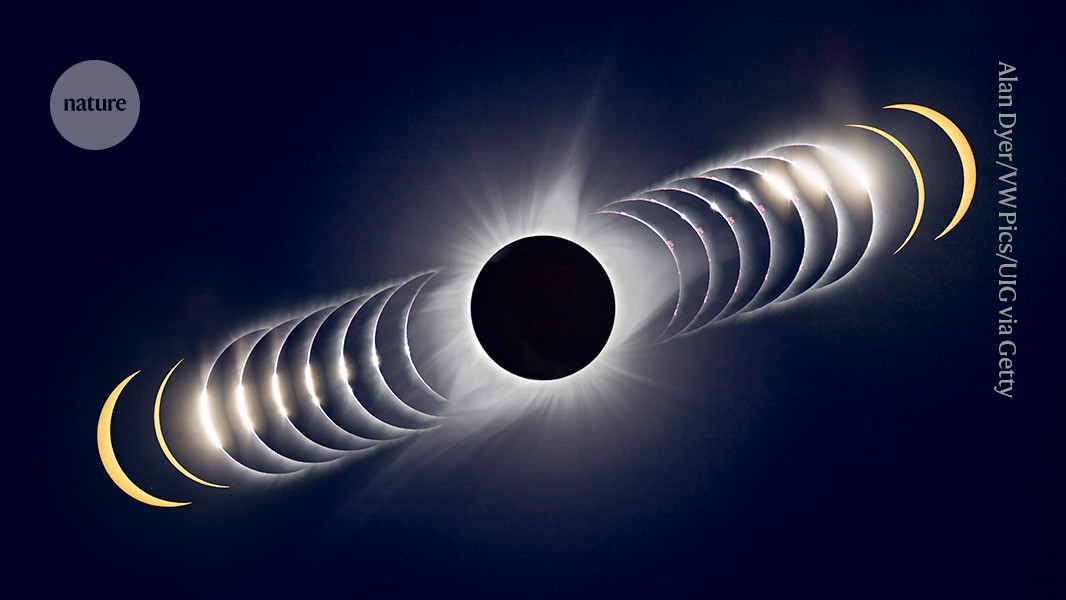

Researchers in North America are gearing up for their chance to observe the Sun’s corona — its wispy outer atmosphere — like never before. Normally hidden to the naked eye by the Sun’s glare, the corona will be visible to millions from Sinaloa, Mexico, to Newfoundland, Canada, when the Moon blocks the solar disk during the total eclipse on 8 April. Every 11 years the solar maximum occurs, and the event coincides with it. During this time, the Sun’s magnetic fields intensify, creating sunspots, fiery loops of plasma and exciting structures in the corona.

The craft will have to fly in precise formation down to millimeter accuracy using radio and satellite navigation, cameras, and a laser beam. ESA technology director Dietmar Pilz said in a statement that getting the two to “act as if they are one enormous 150-m long instrument” will be an “extremely technical” challenge. The ESA says it’s targeting six-hour eclipse observations for each of the crafts’ 19-hour, 36-minute orbits.

One reason scientists are so eager to study the Sun’s corona is its role in our solar system’s weather. Aside from being mysteriously hotter than the Sun’s surface, it contributes to solar wind, and its coronal mass ejections have potential effects on Earth, ranging from the dancing lights of the planet’s auroras to widespread electrical outages (recall every headline you’ve seen predicting a solar storm-induced internet apocalypse). One goal of the Proba-2 mission is to measure the Sun’s total energy output to inform climate modeling.

The coronagraphs on Earth and in space are limited by the light’s diffract or spill over the edge of the light blocking disk. Building the occluding disk into a single craft is not practical because it is too far away. The ESA says in its release that NASA attempted to pull something similar off by using an Apollo capsule to block out the Sun for a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in 1975.

Proba-3 Observations of the Solar Maximum and Beyond: Predictions for the April 8th Solar Eclipse and their Effects on the Corona

The agency hopes to launch the Proba-3 mission in September. Its release today comes as much of the US is getting ready to watch on April 8th as the ultimate occulter — the Moon — traverses the Sun and creates a total eclipse that will swing from South Texas to Maine.

Sometimes, these prominences can snap explosively to form a coronal mass ejection. In the event of a big solar event, billions of tons of relatively cool (10,000 C) solar energy are ejected from the sun and spread around in the corona, whose temperature can reach a million C. Habbal says that because of the solar maximum, viewers have a good chance of seeing a coronal mass ejection. She says that the best opportunity for figuring out how these fluids co-exist and interact is through eclipses.

Earth experiences total eclipses roughly once every 18 months. Most people can’t perceive their paths in remote areas. The last time a total eclipse passed over North America was in 2017. The path of totality in which the Moon completely blocks the solar disk would not allow for the same Sun to be seen during this eclipse. The Sun was close to its minimum during the previous eclipse.

The preview of how it will look was released last month by San Diego’s Predictive Science. The team used the Sun’s surface magnetic fields and real-time satellite data to make the prediction. “The Sun is quite chaotic,” Downs says. So forecasting the corona’s appearance is as difficult as predicting cloud movement — the mention of which is a source of anxiety for eclipse chasers. Clouds could obscure the eclipse from the view of many on 8 April.

By comparing the locations of streamers and holes in the actual eclipse and the simulation, the firm’s scientists will be able to validate and improve their model for future applications, including space-weather forecasting, Downs says.

Habbal and his team of 40 researchers are using high-speed cameras and high-resolution sensors to capture small changes in the corona during the eclipse. The scientists are spread across three different sites in Texas and Arkansas, to make sure they have the clearest view possible.

One group that is not worried about clouds is the Airborne Coronal Emission Surveyor (ACES) team. These scientists will fly in a Gulfstream V jet above the clouds, at an altitude exceeding 13 kilometres. They will interfere with their corona measurement by putting them over aLayer of water vapour in Earth’s atmosphere that absorbsinfrared light. Chad Madsen, an astrophysicist at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and an ACES participant, says the team is interested in studying one particularly long streamer in the Predictive Science forecast.

The team will measure infrared light emitted by the streamer to determine the strength of the magnetic fields in the part of the corona where it appears and the makeup of ions along various segments of the streamer, Madsen says. The corona has magnetic fields that affect the light in it.

Source: Total solar eclipse 2024: how it will help scientists to study the Sun

Adding more seconds to the maximum time that viewers can see on the ground (after a plane landing) using the STAR detector and the KLOE-II Detector

90 more seconds of observation time will be added to the maximum amount of time that viewers on the ground can see, thanks to their flight.