A small organ will grow in the person’s own body in a new trial

LYGenesis is developing liver-regeneration treatments using a donor liver for transplanting human livers, including a patient’s condition

LyGenesis has ambitions beyond mini livers, too. The company is now testing similar approaches to grow kidney and pancreas cells in the lymph nodes of animals, Hufford says.

Not all donor livers are matched to a transplant patient. Sometimes they’re not the right blood type, or they may be too fatty for use. But they’re still viable for the LyGenesis process—and one donated liver has enough cells, Hufford says, to treat up to 75 people.

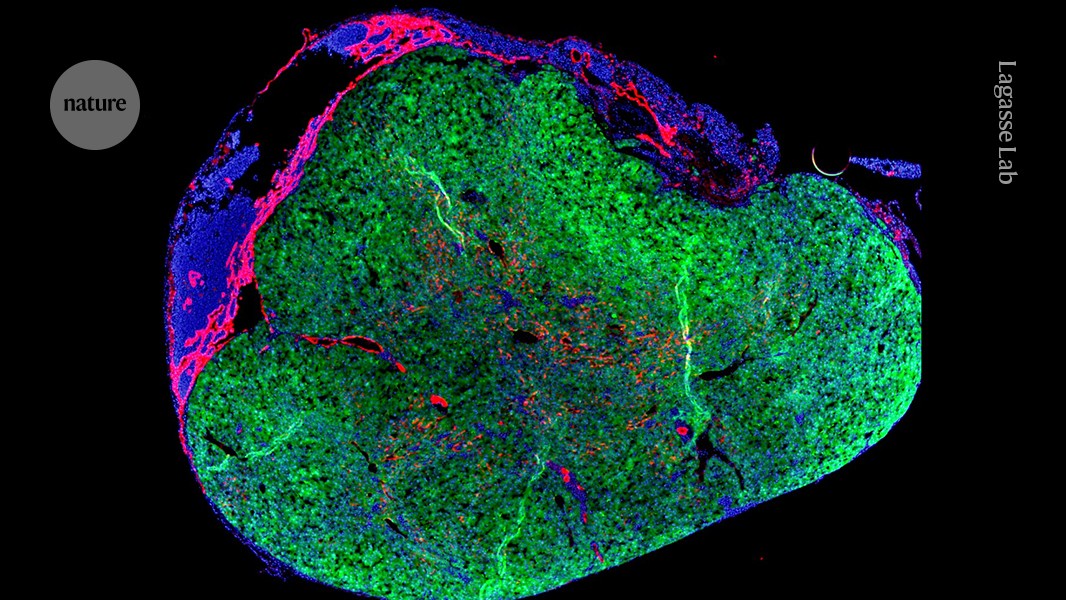

The LYGenesis chose the tissues closest to the body in order to make it easier to repair itself. The only organ with the ability of regenerating even when it is damaged is the liver, which also releases growth factors and other molecule in an attempt to do so. The donor cells are capable of forming new structures.

“It’s a very bold and incredibly innovative idea,” says Valerie Gouon-Evans, a liver-regeneration specialist at Boston University in Massachusetts, who is not involved with the company.

The person who had the treatment on 25 March is well and is no longer at the clinic, said Michael Hufford, chief executive of lyGenesis, which is based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Stuart Forbes, a hepatologist at the University of Edinburgh, said that the person needs to take immunosuppressive drugs so that their body doesn’t reject the donor cells.

Development of an End-to-End Clinical Trial to Determine the Number of Mini-Liards that Will Stabilize a Patient’s Liver

More than 50,000 people in the United States die each year with liver disease. In the end stage of the disease, scar tissue that has accumulated prevents the organ from filtering toxic substances in the blood, and can lead to infection or liver cancer.

There are reasons to think that the organs won’t grow indefinitely. The mini organs rely on chemical distress signals from the failing liver to grow; once the new organs have stabilized blood filtering, they will stop growing because that distress signal disappears, he says. But it’s not yet clear precisely how large the mini-livers will become in humans, he adds.

Hufford says the company plans to enroll 12 people in the second phase of the trial by 2025 and publish their results a year later. The trial that was approved by US regulators in 2020 will measure participant safety, survival time and quality of life after treatment, which will help establish an ideal number of mini livers to stable a person’s health. In order to decide if the extra organs can help the procedure succeed, clinicians will inject Liver cells in up to five people.

The hope is that the mini livers can be used to provide a stopgap until there is a transplant or healthy people can be treated for portal hypertension. “That would be amazing, because these patients currently have no other treatment options,” Gouon-Evans says.