Does a cancer vaccine work?

In situ immunization: The role of immune response in vaccination for pancreatic cancers, Lymphoma and Lyman-alpha

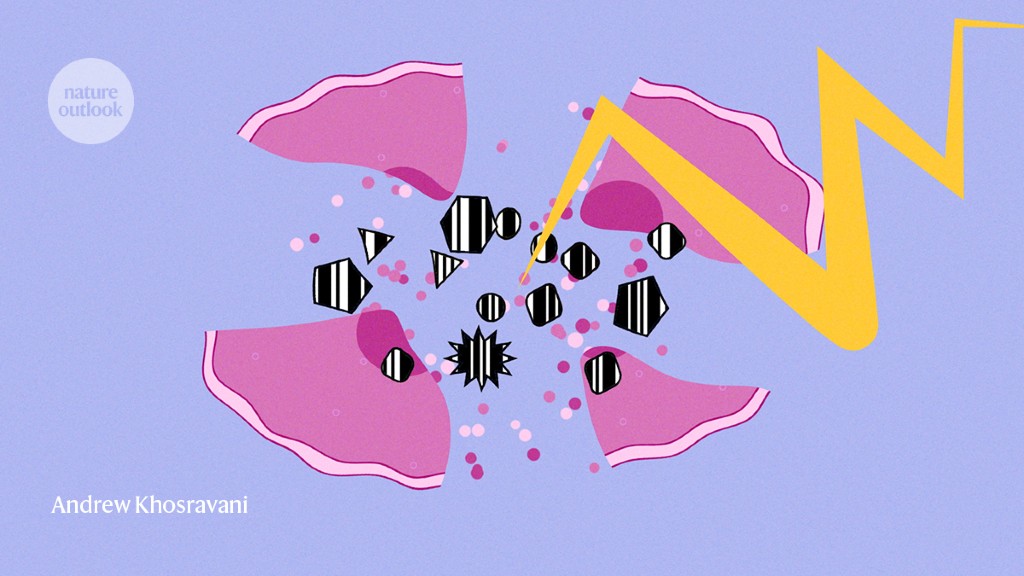

Another approach — and the furthest removed from conventional immunization — is in situ vaccination, in which the whole process takes place in an individual’s body. Rather than delivering antigens through an injection, this method aims to make use of those that are already there, in the tumour. Radiotherapy or a virus is used to kill cancer cells, releasing neoantigens locally. Simultaneously, the patient is given drugs that mobilize and activate dendritic cells so that they take up these neoantigens and instigate an immune response.

Initial efforts closely resembled conventional vaccines for infectious diseases, delivering one or a few proteins that are commonly expressed by certain cancers. The failure of several shared antigen vaccines in large clinical trials in the mid-2010s shifted researchers’ attention towards more-personalized approaches.

Pancreatic cancer is the most common form of cancer. In a phase I trial of a personalized mRNA vaccine, half of the participants developed T cells targeted to cancer neoantigens6. The group withrence-free survival was more stable than those who didn’t respond.

There is a disease called Lymphoma. A phase I/II trial of an in situ vaccine that combined radiotherapy with signalling molecules that mobilize and activate dendritic cells showed evidence of tumour regression in 8 of 11 people who were treated8.

Unwieldy trials. Testing multiple combinations of agents makes clinical trials more complex. Timing when to give a vaccine is a complicating factor.

There is immunity monitoring. Tracking immunity is important for vaccine effectiveness. For cancer vaccines, new T-cell monitoring techniques are needed.

Consistency. Logistical challenges could be caused by personalized cancer vaccines. Keeping costs down and availability high will be the most important things to do.