A new satellite will be able to observe climate-warming pollution

MethaneSAT: A Mission to See the Oil and Gas Industry through the Lens of a Global Measuring Satellite. Is it Still Relevant?

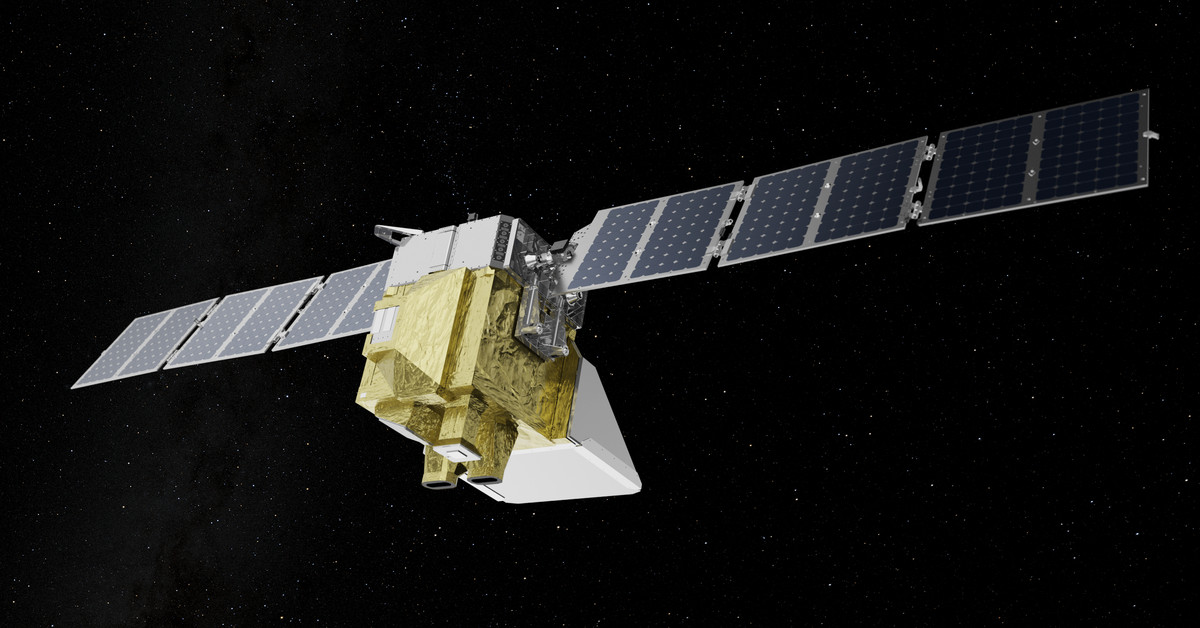

In the past six years EDF put together a team – including scientists from Harvard University and other groups – to build a satellite to get a better picture of the oil industry. The satellite has sensors specifically designed to pick up the fingerprint of the methane molecule. The sensors now orbiting in space will then send data back to Earth in the coming months.

Carbon dioxide traps heat for hundreds of years in the atmosphere. Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas that can have a large effect on climate change in a relatively short time.

By early summer, MethaneSAT should start releasing some data. A complete picture of major oil and gas basins around the world isn’t expected until 2025, data EDF says will be available on MethaneSAT’s website and Google Earth Engine.

If this mission is successful, it could be a game-changer by allowing policymakers to assess how much progress they’re making on climate action based on real-world measures of pollution rather than estimates based on companies self-reporting their emissions.

“What we’ve learned over our decade of doing field measurements is that actually, when you measure actual emissions in the field, it turns out that the total magnitude of emissions coming from the industry is much higher than what’s being reported by them using engineering calculations,” Mark Brownstein, EDF senior vice president of energy transition, said during a press briefing on Friday.

MethaneSAT: How will the oil and gas industry know what is going on, and how will it affect the U.S. Environmental Protection?

Building and launching the satellite cost $88 million, according to EDF. The Bezos Earth Fund gave EDF a $100 million grant in 2020 to help get MethaneSAT off the ground, making it one of the project’s biggest funders. The New Zealand Space Agency launched their first funded space mission.

VANDENBERG SPACE FORCE BASE, Calif. — Not far from the Pacific Ocean, where just to the south, oil platforms dot the horizon, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket blasted into space Monday with dozens of satellites on board.

The oil and gas industry has historically had a culture of confidentiality, says Antoine Halff, chief analyst at Kayrros, a climate analytics firm. He says that they like to keep their data private. I think there is a cultural apprehension with the transparency provided by independent monitoring.

When this satellite is fully operational in the coming months, it will provide data that will be free to the public. That will allow governments, researchers and others to have an unbiased view from space of most oil and gas operations, says Adam Brandt, a professor in the Department of Energy Science and Engineering at Stanford University who was not involved with the project.

“The beauty of having MethaneSAT,” Brandt says, is “we don’t have to ask [oil companies] permission nicely to go on site and make measurements, right?”

But focusing on the oil and gas sector was strategic, Hamburg says. There is a lot of players in the oil and gas industry. “The ability to remediate is much greater and it’s cost-effective,” he says.

The hope is that regulators will use this data, Hamburg says. There is interest. There are conversations with other regulators as well as the U.S. EPA.

A spokesperson for the EPA said in an emailed statement that the EPA’s new rule “has a mechanism for third-party notifiers using approved remote sensing technologies to be certified – enabling them to notify EPA of methane super-emitter events.” Large amounts of methane release can cause super-emitter events. The EPA said that “EDF, along with other owners of remote sensors, may apply to be certified.”

“Our industry’s experience shows that one really needs to use a range of technologies working together across their strengths and weaknesses in order to get a truly accurate picture of where you have methane emissions,” Padilla says.

“This is an industry that recognizes that their reputation, their markets are under threat,” Hamburg says. You want to prove you’re a better actor if you compete in a world where demand is going down.