The CDC may be rethinking its guidance

The Effects of COVID-19 on Public Health Policies and Workplace Safety: An Observation from a Washington Post Interview with Dr. Anand Parekh

It doesn’t mean that there isn’t still risks for people posed by respiratory pathogens when we harmonize our policies, Nuzzo says.

Public health experts say a change in CDC guidance could make a big difference for workplace policies. If the CDC no longer recommends staying home for a week with COVID-19, workers may be forced to go into work while still sick. They may spread the coronaviruses.

“I think people forget that it’s not okay to be moving around if you’re infectious, because of the risk to vulnerable people,” she says. “We have to protect people who are too old or young, as well as people who are immunocompromised, and they need protection through the community.”

The CDC may stop telling people how to be isolated from one another because of COVID-19. Several unnamed CDC officials are behind the reported change in The Washington Post.

According to the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health, this change shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that COVID-19 is less contagious.

The policy change under consideration may be a reflection of the fact that the impacts of spreading COVID-19 are less consequential than they used to be, at least from a public health perspective. Deaths and hospitalizations went up this winter, but nowhere near as high as they did in previous years. This virus season hospitals were mostly OK.

The reality that many Americans weren’t following it could lead to changing the guidance. Isolation “is really hard, and it takes a lot of work,” says Dr. Anand Parekh, chief medical adviser at the Bipartisan Policy Center. He was in a home that had been isolated for the first five days after he spoke to NPR. He worked, ate and slept alone to avoid exposing his family members, including three young children.

“For a lot of people, it’s not possible — how they live, where they live, how many people are in the household, their jobs — whether they have paid leave, whether they could work virtually,” he says.

Why does public health really matter? Jessica Rivera, an epidemiologist and communications director at the de Beaumont Foundation, says COVID-19 testing should not be accompanied by seat belts

In addition, testing is more expensive and harder to access than it used to be, so people may not even know they have COVID-19, let alone take steps to isolate, Parekh says.

Even if people ignore the current public health advice, Jessica Malaty Rivera, an epidemiologist and communications adviser to the de Beaumont Foundation, believes that the federal government’s public health advice should be guiding people.

“People aren’t really wearing a seat belt, so I guess we can say that seat belts don’t matter, right?” she says. “That kind of defeats the purpose of providing evidence-based information — that’s still the responsibility of public health to do that.”

It makes it harder for people who are vulnerable, like those who are young, old andimmunocompromised.

The CDC has yet to confirm the report. The CDC has “no new guidelines to announce at this time,” according to an email from an agency spokesman. We use the best evidence to make decisions that will keep communities healthy and safe.

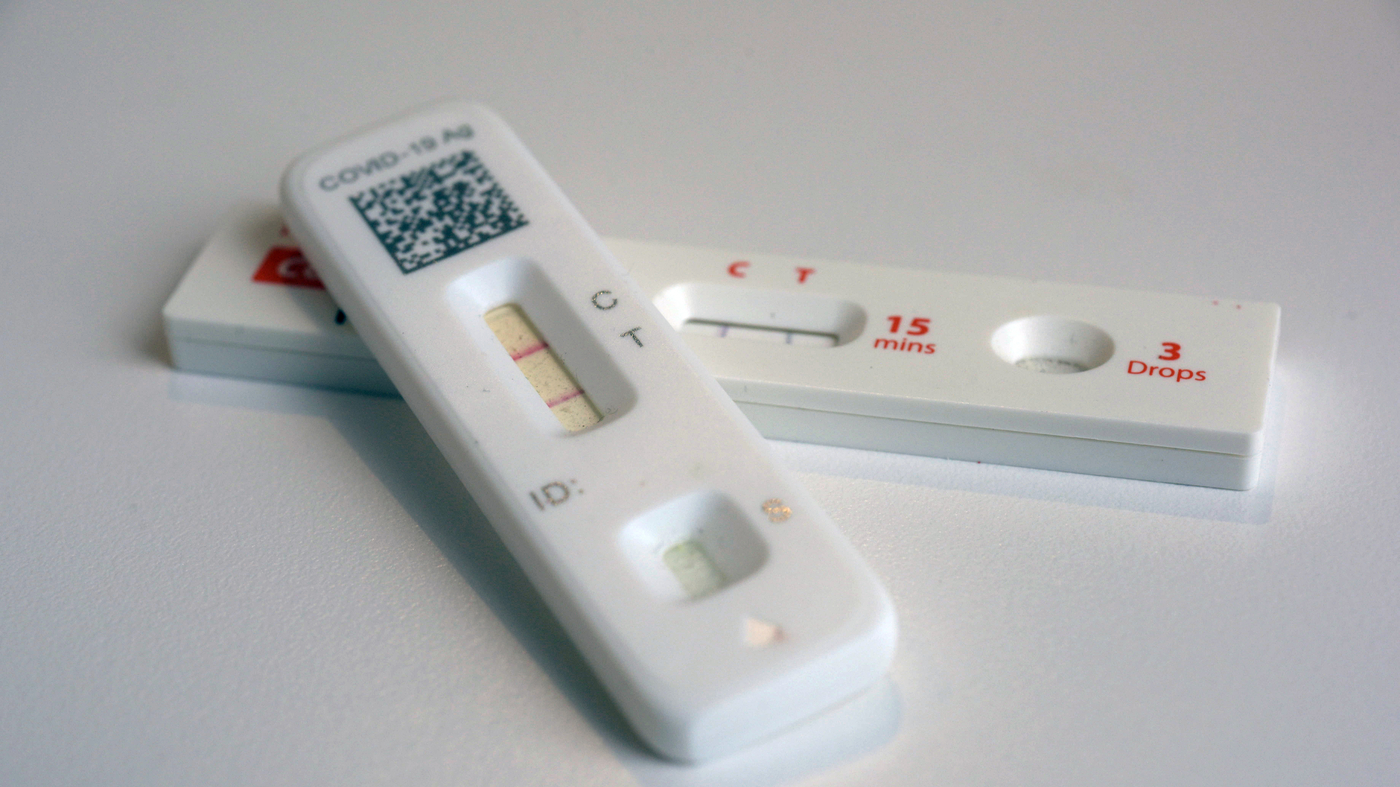

Currently, people who test positive are advised to stay home for at least five days to reduce the chances of spreading the coronavirus to others. According to the officials, the agency will tell people to rely on symptoms. If a person doesn’t have a fever and the person’s symptoms are mild or resolving, they could still go to school or work. These changes could come as early as April.