Sam Bankman-Fried didn’t ask where the $8 billion went

Alameda and Ellison Lost $8 Billion, and What Did Bankman-Fried Tell Us About Their Relationship to FTX?

Let’s say I am the owner of a hedge fund, and one fine June day, my employees come to me and say, “Hey, Liz, we have an accounting problem. We are missing several billion dollars.” I don’t know how to react.

The software bug that caused Alameda to overestimate their debt to FTX was not what Bankman-Fried reacted to. Oddly, he didn’t react negatively to learning that Alameda still owed FTX $8 billion even after fixing the bug. Instead, Bankman-Fried directed Ellison to make investments and repay third party loans.

The June 13th, 2022, Alameda balance sheet shows the money it was borrowing from FTX as ‘ftx borrows.’ Bankman-Fried was hazy on this as well.

The charges in this case hinge on conspiracy and intentional deceit. Just losing $8 billion is not a crime, though it is very embarrassing. (Even losing $900 million is very embarrassing because people will make jokes about it forever!) Bankman- Fried would be guilty of a crime, if he lied about how safe FTX was.

If Bankman-Fried answered long, the government would frame his answers as too vague, and if he answered briefly, they would say he sounded evasive. Look, I was there — and I know word salad and evasions when I hear them. It’s kind of my business. The answers Bankman-Fried gave to the questions he wasn’t fond of were not good. Saying he was “far from polished,” and “was himself; he was Sam” doesn’t really get the work done. The Bankman-Fried was a lot funnier than the one we saw on cross, and it didn’t get the work done. Bankman-Fried was an awful lot like the one we already knew.

“So it’s your testimony that your supervisees told you to stop asking questions?” Sassoon asked. She had a tone that was so level it was hard to tell what was happening. Who had Bankman- Fried asked to spend $8 billion? “I wasn’t trying to build out blame for it,” he said. He was focused on solutions. Did he fire anyone? Nope!

If you are wondering how Bankman-Fried’s parents reacted to this, I can’t tell you — they weren’t there. I did not feel like I could really blame them. I wouldn’t want my child to be put down. The jurors were watching the operation attentively. I suppose for most of us, $8 billion has a way of focusing the mind.

The Bankman-Fried Discriminating Between FTX and the Bahamas: What Have You Done to Misplace? What Have I Done About Them?

Look, uttering phrases like “hole isn’t really the word I would use” and responding to a question by saying you wanted “a few more qualifiers and scoping on it” do not, as a general rule, bode well for your believability. This will win a lot of nerd arguments. But this is a courtroom, and I have come to believe that if you know the meaning of the word “epistemology,” you absolutely should not testify in your own defense.

Bankman- Fried was the first witness to speak directly to his state of mind on the stand. You could have a lot of questions that you might not want to answer on cross-examination if you tell your side of the story. I have watched a lot of crosses. I think this was the worst thing to have ever happened to me.

There was an email from Bankman- Fried that said they were “deeply grateful” for what the Bahamas did for FTX. Bankman- Fried wrote that as a token of gratitude.

We’d be very happy to open up all of the withdrawals for all of the customers in the Caribbean. They’d be able to withdraw all their assets tomorrow. It’s your call whether you want us to do this, but we are more than happy to and would consider it the very least of our duty to the country, and could open it up immediately if you reply saying you want us to. We are going to go ahead and do it tomorrow, if you don’t reply by then.

Bankman-Fried did indeed open withdrawals for Bahamian customers. The upshot of this testimony seemed to be that Bankman-Fried had a cozy, perhaps even inappropriately cozy, relationship with the Bahamian government — which isn’t what he’s on trial for but probably doesn’t make him look any better to a jury.

Closing arguments start tomorrow, and then the case will be handed to the jury. I will continue to ponder the appropriate response to misplace $8 billion. Is that Crying? Fainting? I would not know if it is padel tennis. Net sports are not part of my area, and nobody has ever given me $8 billion to misplace.

Taking the stand was always going to be a risky move — one few criminal defendants make. Less than one minute into the cross-examination by the prosecution, it was clear why.

Time and time again, the U.S. government’s lawyers pointed to contradictions between what Bankman-Fried said in public and what he said — and did — in private, as they continued to build a case that he orchestrated one of the largest financial frauds in history.

The stakes are high for Bankman-Fried. He could go on to spend the rest of his life in prison if he is found guilty of securities fraud.

Sam Bankman–Fried’s Trial: How a General Manager and Business Partner of FTX Flrolled to Alameda Research Funded Luxury Real Estate

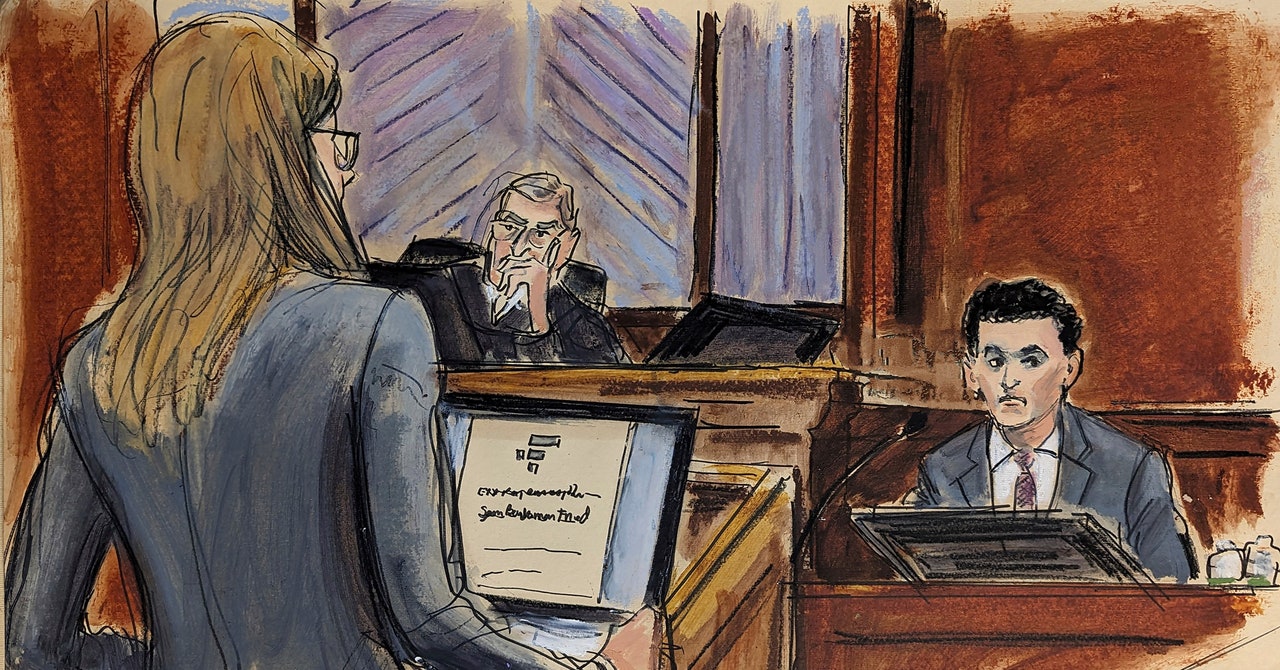

Veteran prosecutor Danielle Sassoon, a former clerk with the late Justice Antonin Scalia, is known to be an effective litigator, and in her cross-examination of the defendant, she delivered.

For almost eight hours, the assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York asked Bankman-Fried a litany of incisive questions. She moved quickly, and whenever the defendant hesitated, she dug in.

Bankman-Fried was getting more and more annoyed with each hour. He disagreed with how he characterized his past comments, in trial testimony and media reports.

At times he seemed to be out of it. Bankman- Fried did not want the prosecutor to read his statements aloud, and he slumped in front of the microphone.

Bankman-Fried did media interviews even after his companies collapsed and he was indicted. He was critical of X, which was formerly known as TWITTER. He even tried to start his own e-mail newsletter.

Bankman-Fried had claimed that Sassoon was a person who struggled to keep up with the speed and magnitude of FTX’s growth, but failed to recognize the extent of its troubles.

The seasoned prosecutor sought to paint Bankman-Fried as something else entirely, as someone who directed his subordinates to funnel billions of dollars from FTX’s users to Alameda Research, to plug holes in the company’s balance sheet, and to fund lavish expenses.

FTX used private planes to ferry packages from the United States to The Bahamas, and Bankman-Fried bought luxury real estate.

The Case of Mark Bankman-Fried: An Intrvert who didn’t hurt anyone on purpose, but an Intrvert like a Kind of Kid Who Don’t Drink

Sassoon was in a position to be prepared. When Bankman-Fried said he couldn’t remember something, she would confront him with the evidence in the form of an email, or a tweet, or an excerpt from an interview.

The main thing the closing arguments made clear was how lopsided the case was. Bankman-Fried’s defense seems to be that he’s a nice boy who wouldn’t hurt anyone on purpose. An introvert! Who doesn’t even do recreational drugs! Bankman-Fried made a noise when he crumpled the water bottle in his hand as Cohen told the jury to keep him in mind. Glancing over, I saw he was looking directly at the jury, with an expression on his face that suggested he might cry.

Bankman-Fried also told the court that he made “a number of small mistakes and a number of larger mistakes.” He said that the biggest one was not having a dedicated risk management team.

Bankman-Fried said that they did not have a chief risk officer. “We had a number of people who were involved to some extent in managing risk, but no one dedicated to it, and there were significant oversights.”

He blamed his top lieutenants at FTX and Alameda for mismanaging things, including Caroline Ellison, a former girlfriend and CEO of Alameda, who had testified he had directed her to commit crimes.

Ellison failed to hedge the firm’s investments adequately, making it vulnerable to steep market downturns, according to Bankman-Fried.

Michael Bankman-Fried: When did he run his own life? How did the prosecution close his book about banking and financial crime?

The best-selling author is Michael Lewis who has just penned a book on Bankman-Fried. Wearing Hoka running shoes and a down jacket, he followed the proceedings in one of the overflow rooms before he snagged a seat in the courtroom itself — not in the rows of reporters, but in a seat near Bankman-Fried’s friends and family.

The testimony also attracted an array of celebrities including actor Ben McKenzie. The former star of “The O.C.” and “Gotham” is now a “crypto skeptic” and the co-author of a bestseller about cryptocurrency.

And crypto influencer Tiffany Fong, who has gained some celebrity during the trial after she interviewed Bankman-Fried for hours when he was under house arrest, has summarized each day’s proceedings in video digests.

We learned Bankman-Fried was working very hard, 12 hours a day, which seemed low: Bankman-Fried had previously testified he worked as many as 22 hours a day. But I couldn’t tell you what exactly he was doing for all that time, as there was precious little testimony about it. Similarly, I heard a lot about a data protection policy the defense could not produce.

So I was sympathetic to Mark Cohen, the lawyer for the defense, who didn’t seem like he had much to work with. Did his closing statement cause things to get worse? To begin with, he appeared to be reading directly from a document he’d created, rather than looking up at the jury. He spoke softly, almost in a monotone, as though he was hoping to lull the jurors to sleep.

Cohen said the prosecution was trying to make Bankman-Fried into a villain. The jury saw a number of photos that showed Bankman- Fried hanging out with a number of people, including Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. I don’t know why Cohen chose to remind us of these photos, but he did. Yes, the prosecution was painting an uncharitable picture of Bankman-Fried but there’s no need to reinforce it.

That closing statement honestly could have ended after the first hour. The evidence that Bankman-Fried was involved — from his Google Meet with the other alleged co-conspirators, to the metadata linking him to various incriminating spreadsheets, to the funds traced to entities he controlled — would have been enough. But we got a few more hours anyway, as though Roos had rented a backhoe for his pile of evidence and was going to get as much use out of it as possible.

As Roos spoke, the jury was focused very closely on him. No one appeared to be napping. Many jurors were taking notes, and I didn’t see anyone look at the clock. Though Roos was interrupted by an AV mishap when the screens used to show the jurors the evidence briefly went out in the middle row, the closing argument was smooth. Roos talked directly to the jury, glancing occasionally at his own notes.

The Trial of Michael Cohen: On the Role of Anomalous Detection in the Making of a Business in Alameda

Perhaps predictably, Cohen emphasized that mistakes aren’t illegal. He wanted to show Alameda as a legitimate, innovative business. It was difficult to understand what they were doing, but never mind. At its peak, the valuation of FTX was very high.

This line of argument was the most viable route for the defense, says Daniel Richman, a former prosecutor and professor at Columbia Law School. But it was a Hail Mary nonetheless, in no small part because Bankman-Fried, in his parade of interviews prior to his arrest, had given the prosecution length upon length of rope with which to hang him.