Cash transfers have a negative effect on mortality in low and middle-income countries

The impact of poverty on the world’s most developed developed developed countries during the 20th century, and an analysis of adult and child mortality during the global cash transfer pandemic

Less than 50% of the world’s population lived on less than $6 a day, and more than 8% lived in extreme poverty. Poverty has insidious effects on housing stability, education, health and life expectancy.

The pandemic drove 97 million additional people into extreme poverty in 2020, according to a World Bank estimate, prompting more countries to start cash transfer programs. Of 962 such programs worldwide, 672 were introduced during the pandemic.

We performed an analysis of adult and child mortality during a study period when a lot of countries introduced cash transfer programmes.

“There’s some concerns about whether these programs are sustainable, whether governments can and should pay for them,” said Harsha Thirumurthy, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania and a co-author of the analysis.

The data included information on more than 4 million adults and nearly 3 million children. Roughly 300,000 deaths were recorded during the study. It is possible that recipients received less than $100 in per capita income.

There aren’t amounts that are as large as in the US when it comes to guaranteed income programs.

Still, the findings are relevant even for high-income countries, said Audrey Pettifor, a social epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who studies cash transfers for H.I.V. prevention and women’s health.

She said the data doesn’t back that up, as donors often worry that beneficiaries may misuse the funds to buy alcohol, junk food or other nonessential items.

“These social protection programs actually account for the vast majority of the income” in households in places like South Africa, Dr. Pettifor said. One would expect the spillover effects.

Berk zler is an analyst in the research division of the World Bank. Cash transfers are often accompanied by improvements to health care services or other infrastructure that helps communities, he noted.

The effect of cash transfer programmes on estimates of outcomes: a country-year analysis based on dynamic effect estimates and Poisson regression with conceptual justifications

The study did not look at adults older than 60 or at distinct features of the programs, such as duration or frequency of the payments, whether the beneficiaries are men or women, how the money is delivered or whether it is bundled with counseling or education.

We did not use statistical methods to predetermine sample size. We used SAS V.9.4, R V.3.5.2, ggplot2 and did2s packages to perform statistical analyses.

Fourth, we assessed whether individual countries might be outliers for key outcomes by assessing whether estimates for women changed substantially after excluding each country individually.

The recent findings of differences-in-differences analyses show that estimates may be biased if there is heterogeneity in intervention effects. When there is heterogeneity only in time since the intervention, this concern can be mitigated through use of temporal analysis with dynamic effect estimates. We looked at whether a proposed alternative linear estimation was in line with our findings. We repeated the primary analysis after removing country years after year 5 of the cash transfer programme69 to find out how much this bias was influenced by later country years.

We used modified Poisson regression models that were based on conceptual justifications and to be consistent with prior literature, but we also evaluated the results when using logistic and linear models.

Fixed effects for time-in variant differences among countries and year fixed effects for secular trends in mortality were included. Standard errors were clustered at the country level to relax the assumption of independent and identically distributed error terms.

For individual-level covariates, we included age and rural or urban setting in all analyses. In the child analyses, we also included sex, mother’s age, and birth order. We did not include other variables that could be affected by the receipt of cash transfers or the relationship between cash transfer programmes and mortality.

Cash transfer programmes with coverage between 2 and 5% were excluded from our comparison country-years. Comparison country-years were therefore defined as those during which there were no active cash transfer programmes, or cash transfer programmes (or combination of programmes) had coverage <2%.

Our primary explanatory variable was a binary variable set to 1 if a cash transfer programme (or combination of programmes) with total impoverished population coverage greater than 5% was active in the respondent’s country during that year. We were prevented from considering coverage as a long-term exposure since beneficiary data was only available for a limited number of years. We chose 5% based on our prior analyses showing this threshold was associated with improvements in HIV-related outcomes26, but conducted subgroup analyses (described below) to explore the association with different levels of coverage. We excluded intervention countries that lacked at least two years of mortality data prior to the cash transfer period.

The additional data that we took about the primary respondents were related to their age, rural or urban setting, wealth quintile, and education levels. Respondents were classified into wealth quintiles using the DHS Wealth Index, a composite measure of households’ cumulative living standard generated using a principal components analysis based on ownership of certain assets, materials used for housing construction, and types of water access and sanitation facilities55.

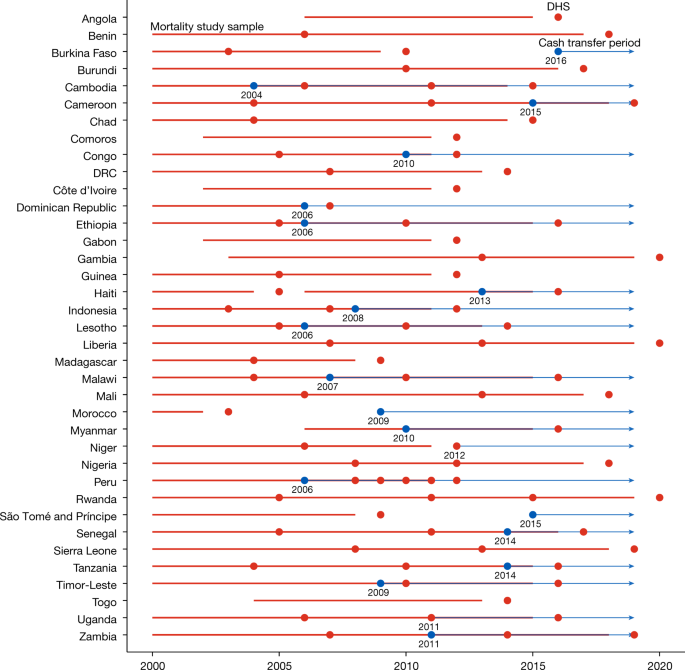

We used demographic and health surveys to estimate mortality, for both adults and children. In many LMICs, the DHS is done every five years. They use a two-stage cluster sampling design to produce national and sub-national estimates for a variety of indicators that are representative of their target populations54. The first stage involves systematic selection of enumeration areas drawn from census files with probability proportional to population size, and the second stage involves a random sampling of households from each enumeration area. Primary respondents were all female household members of reproductive ages (15–49 years). Procedures and questionnaires for DHS have been reviewed and approved by the ICF Institutional Review Board. The analysed data was not made public. In accordance with standard procedures for secondary data analysis, the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board waived ethical review.