Do we grin or adjust our concerns?

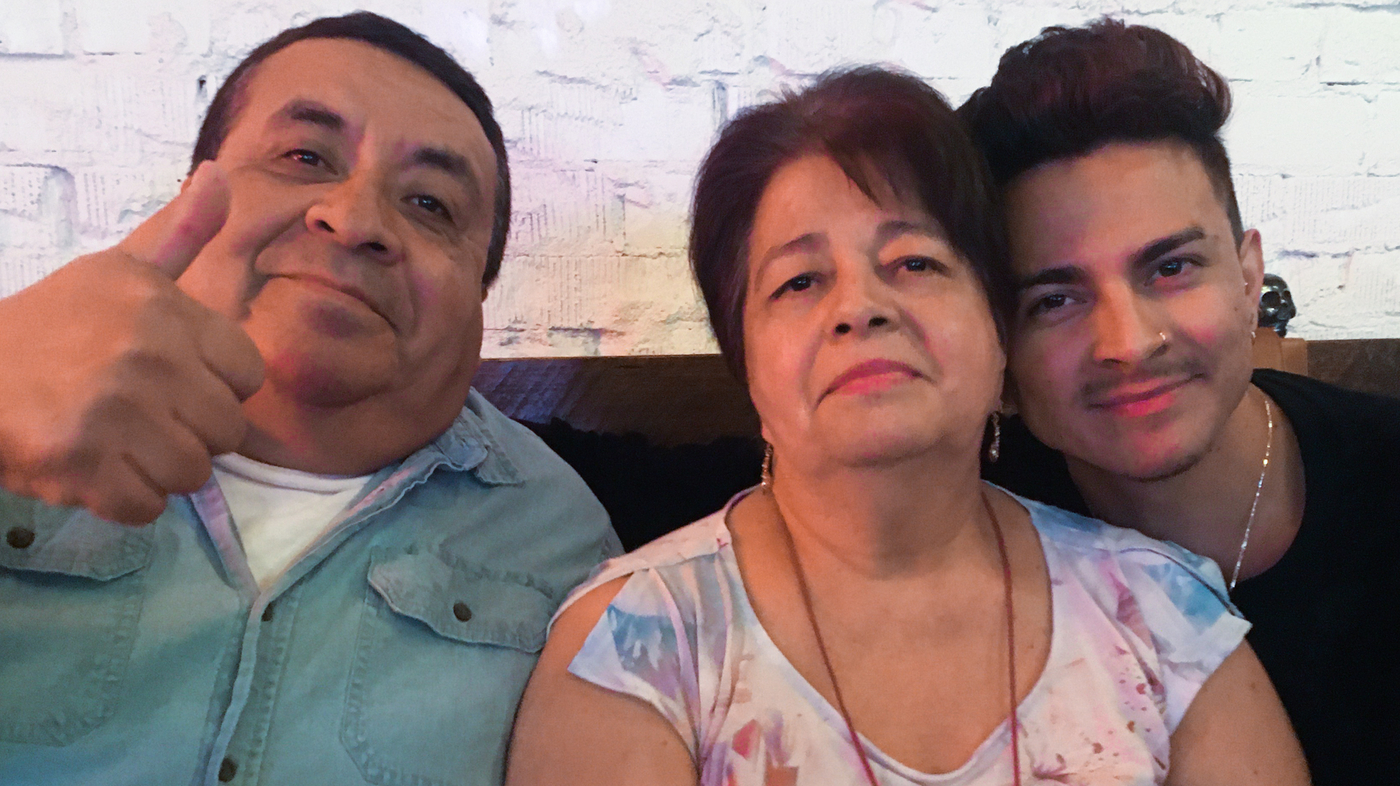

The Aldaco Family of Phoenix, Ariz., during the First Year of COVID: The Effects of Parent and Teacher Disturbances

As NPR reporters have covered the twists and turns of the pandemic, they have talked to hundreds of people – local public health workers, long COVID patients and people who lost loved ones to COVID, among many others. Several people were called byNPR to talk about their reflections on the end of the public health emergency.

In March of 2021, there were two granduncles who had passed away. His grandfather was also from COVID. For the Aldaco family of Phoenix, Ariz., these three deaths – within six months of each other – shattered a generation of men.

He explains that after the swine flu took their dad away, they left that parent. We were still dealing with the loss of my dad, so we weren’t prepared for that. Virginia had recovered from a severe case of COVID for which she’d been hospitalized, and Lerma’s family wonders if the strokes may have been a post-COVID complication.

They are dealing with the aftermath of that first year of the Pandemic, the huge stress on parents and kids, as well as the fact that the school was closed. One positive legacy of that time is that parents appreciated when their children were in virtual classrooms. “People were like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I don’t want to be my child’s teacher! Please send them back to school. I value the teacher, the bus driver, the cooks, because I want everybody in school!'” she recalls. “I saw that people were very fond of educators, but they might have forgotten about it today.”

Mental health of Lerma’s family and post-pandemic recovery of her husband’s dementia after taking a job as a bus driver

Lerma moved from Phoenix to Los Angeles last June. He took a job as a city bus driver, which is easier, he says. “Now, I don’t take work and the stress of it home with me,” he says, “I’m able to handle my mental health a little bit better, and cope with what I need to cope with post-pandemic.”

In November 2021, Semhar Fisseha shared her story of how she was afflicted with the long COVID and was able to rebuild her life. Once an active parent, she became debilitated and needed a wheelchair for a time.

She says that she is now in a better place with her health and no longer needs a wheelchair, but she is still learning how to deal with an episode. “I learn new ones all the time, but the main ones are not eating on time, not eating enough, temperature change – if I go from cold temperature to heat, I know my body is not able to function,” she says. “My body kind of shuts down – I start slurring my words, I move really slowly. It’s kind of like I’m asleep but I’m not, if I don’t have a snack. I lose my mobility when I’m aware of everything going on. I can’t command my arms, my legs.”

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/05/11/1175463986/public-health-emergency-ends-people-most-affected-reflect

Malachi Stewart: From contact tracing to COVID-19 and what it taught me about the U.S. pandemic and how I got my vaccines

Contact tracing exploded in the early days of the pandemic as a way to help contain the spread of the new virus in the absence of vaccines or much scientific understanding about how the virus spread. Malachi Stewart of the D.C. Department of Health changed over from contact tracing sexually transmitted infections to the COVID-19 team. He explained his job to NPR in April 2020.

He thinks that the epidemic made people understand what the health department is and what it does. “We know how to make people feel like they’re not just a number – one patient said ‘a petri dish of infection’ – but you’re a person,” Stewart says of those early interactions he had when people were first getting infected.

There have been many stories of local public health workers leaving the job because they faced threats or vitriol. Stewart says yes, sometimes fear makes people lash out, but he says he doesn’t take it personally, and that there were plenty of positive connections that are less likely to make the news. “People are afraid, people are processing,” when you tell them on the phone that they are positive, whether for COVID-19 or any other infection. “When you’re in that space with people, that’s not personal.” So you may have gotten people on the phone who were yelling, who were screaming, but they answered the phone the next day – that’s where the care is.” S.S.D.

When COVID vaccines first became available, the shots were in short supply, the distribution was chaotic, and every health department was doing its own thing. She viewed her job as herding a bunch of cats. After toiling behind the scenes on children’s vaccinations for decades, immunization managers around the country were called to roll out life-saving vaccines that could end the pandemic. Suddenly the spotlight was on us, according to Hannan.

The Vaccines for adults were disorganized. There was nothing with public health agencies involved, and you could have a lot of providers in the private sector giving out vaccines.

The government wanted to know how many vaccines were going into arms and who was getting them, as well as how many were being wasted, because of age, race and sex. “We started sharing data in real time, capturing the doses administered and sharing with CDC- something that hadn’t been previously accomplished, enroll hundreds of thousands of private providers,” she says.

As the health emergency ends, “It’s an exciting time to look back at some of the accomplishments and really think about how to sustain them,” Hannan says, “I hope we can learn some lessons about having stable funding for public health services, because there’s nothing more basic than providing life-saving vaccines and making sure everyone has access to them.”

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/05/11/1175463986/public-health-emergency-ends-people-most-affected-reflect

NPR’s Vivian Cheung: Going to the Coal Mine in the Seclusion of the COVID Pandemic, and Seeing the Impending Omicron Wave

In one of many conversations with NPR from her basement, in the seclusion of the pandemic, Hannan defined normalcy as partying in the parking lot at her daughter’s college lacrosse games. I have been tailgating at my daughter’s lacrosse games recently, and it has been fun. She says she missed many events during the flu because she wasn’t able to have those with people she wouldn’t normally see.

In January 2022, in the middle of the omicron wave, Dr. Vivian Cheung became one of the lucky few to get a shot of Evusheld, a drug for immunocompromised people that could help protect them from getting COVID. She told NPR last year that getting the drug was hard due to the short supply.

She’s been able to leave, despite Cheung still feeling vulnerable. Beyond work, she’ll go to the grocery store (at 6 in the morning, when nobody else is there). She’s gone to a few conferences and dined indoors once. Still, she draws the line at crowds and long flights.

Her daily routine still includes the use of masks, they have been in her life before. She thinks the pandemic raised people’s awareness of disabilities and vulnerabilities, but worries that grace and understanding is fading. She says it’s nice not to be the only one when she sees someone wearing a mask. But the other day, as she stood on the street in a mask waiting for an Uber, someone walked up and chastised her, saying, “Don’t you know that COVID is over?”

Cheung is worried that the gaps in data reporting will cause vulnerable people to be at greater risk. She would like to not be a canary in the coalmine, warning others to an impending wave, when she is sick in the hospital. She is eager to get all the protections available to her, and she wants to help start new ones. She keeps tabs on a second generation Evusheld, currently in development, and asks her doctors frequently when she can enroll in the clinical trials. P.H.

Educators also stood on a fault line of the pandemic, as COVID safety protocols interfered with school attendance. Superintendent Alena Zachery-Ross told NPR about how the “test-to-stay” policy was playing out in her Michigan school district in December 2021, after the CDC recommended letting students exposed to the virus stay in school if they tested negative.

There are lasting changes from the pandemic in Ypsilanti schools, Zachery-Ross says. The ventilation systems are different; there are hand sanitizer dispensers all over the place, and more of an awareness about staying home when sick, she says. The district was able to give the laptops to students who needed them. She says that the schools and parents got more used to coordinating and communicating. “I think we can do some of those takeaways that can continue now – so that gives us hope.” S.S.D.

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/05/11/1175463986/public-health-emergency-ends-people-most-affected-reflect

Don’t Clock Out: A Non-Profit Organization to Support Mental Health Care Workers in the Changing Era of the 2022 Pandemic

In January, 2022, Michael Odell, a 27-year-old critical care nurse died by suicide. He died as a cry for health care workers’ mental health. It pushed a group of nurses, including Odell’s closest friends in the profession to start a non-profit organization called Don’t Clock Out to support nurses experiencing mental health crises.

“It’s been a huge learning experience going from this pandemic and starting the organization,” says Joshua Paredes, Odell’s close friend and former roommate. I knew there was a need, but I didn’t expect so much support for my colleagues.

The organization provides peer support, with weekly virtual meetings for health care workers anywhere in the country experiencing burnout and other mental health issues.

“We had to add an extra meeting because we realized that it’s not just nurses that need support, it’s actually the entire health care team,” says Paredes.

Work is a major source of stress for health care workers according to Paredes and his colleagues at Don’t Clock Out. There is a sense of moral injury that healthcare professionals have had to perform in situations that violate an ethical code and have their employers let them down.

The co-founders of Don’t Clock Out worry that the lifting of the declaration will make it more difficult for people to get mental health care.

“There will be an inevitable discontinuation of mental health services for people,” says LeBlanc, who recently lost access to his therapist. They decided to focus on their in-person practice instead of their telepresence clients.

But what gives Paredes hope is the fact that healthcare workers are increasingly recognizing the need to support one another, both for their mental health and to fight for better work environments.

“We’re kind of uniting in new ways, we’re unionizing, we’re communicating across disciplines,” he says, “all under the motivation that we’re building something new to replace what hasn’t worked in the past.”

“My sense of hope is based in the volunteer-led organizations and health care worker-led organizations that are passionate about what they do, because of what happened during the H1N1 epidemic,” he says. “These organizations serve solely to support nurses, residents, other health care workers through the damage that the pandemic has done or the damage that was done prior to the pandemic that we weren’t able to talk about openly.”

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/05/11/1175463986/public-health-emergency-ends-people-most-affected-reflect

The Goats and Soda Blog: Talking about Mental Health, Mental Well-being, and the New Phase of the Influenza

He says that openness about mental health and mental well-being is huge, not just in the healthcare field. “I’m able to have conversations with my family about mental health that I never have dared to have before.”

There were a number of reasons why LeBlanc would like to work as a mental health worker. Starting this fall, he will be attending a Masters program to become a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

The Goats and Soda blog published an FAQ series that touched on everything from possible transmission to whether a glass of wine after a vaccine seems to be ok. We talked to public health experts about how to move forward as the world enters a new phase because the disease seems to be here to stay. We’re willing to answer questions about the new phase of the epidemic at [email protected]. Please include your name in the body of the email. Questions in the follow-up FAQ will be answered by us.

Thomas Bollyky, senior fellow for global health, economics and development at the Council on Foreign Relations, says that a public health emergency is “really designed to spur international cooperation around a public health event that is serious, sudden, unexpected and requires immediate attention.”

The public would have been able to understand why the agencies decided that May 2023 was the right time to end the flu if they had been able to communicate the goals and targets all along. “If the public can’t see progress, it will be harder to convince them next time that these emergency measures are necessary,” says Bollyky.

The announcement that the emergency is over doesn’t mean the virus been vanquished, says Dr. Wafa El-Sadr, director of the Global Health Initiative at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. It’s still infecting thousands – and killing thousands – each week.

“HIV doesn’t have a public health emergency declaration, tetanus doesn’t have a public health emergency declaration, and yet people stay up to date with vaccinations and treatments,” says Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, “People don’t need a public health emergency to take something seriously.”

Nonetheless, the reassuring message from CDC and WHO is that you’re less likely to catch COVID-19 because case counts have dropped due to vigilance and treatments.

But we’re going to be living with COVID-19 for … a while. “It has become clear that this coronaviruses will be with us for the foreseeable future and is an infectious disease that needs to be prevented, treated, and managed like other serious conditions,” says Wen, a mother of two. The focus should shift from population-wide measures to safeguarding the most vulnerable and investing in better vaccines and treatments to help those at highest risk from severe outcomes due to COVID-19.”

Even if you are not high risk, you should be aware that feeling awful is a possibility even if you have no health risks. You might have to miss work. You run a risk of long COVID. There’s a chance you could cause death from the virus, if you come into contact with it.

If you test positive you may be older and have underlying health conditions such as a compromised immune system or diabetes. Don’t think you can beat it on your own. Call your doctor immediately, says Dr. Glatt, the chair of medicine at Mount Sinai South Nassau. There are options for high-risk individuals who are not used. You may be a candidate, which could reduce your possibility of progressing to severe disease.”

For example, there’s the COVID antiviral drug paxlovid — which has been proven to help. A review of federal data found the risk of long-term health problems, hospitalization and death decreases for those who take the medication within 5 days after a COVID-19 infection. That’s according to a study by researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine.

Many physicians interviewed for this story tell us they still take precautions they think warranted. “I wear a mask in my work for patient care in the hospital and the clinic,” says Dr. Luis Ostrosky-Zeichner, who works at the Memorial Hermann healthcare system in Dallas.

“In my personal life,” he adds, “I still have A Purell dispenser in my car and carry a small bottle when I travel. I wear a mask at the airport until the plane takes off so I don’t get to my hotel room while I’m exposed to pollution in my own seat. I still have tests at home and travel with a couple of them.

Many people are happy to doff masks and plunge back into the crowds at transportation hubs, concert arenas and sports venues, but others are understandably nervous.

Malani does believe that too much worry is not good for you: Fear of COVID or severe anxiety out of proportion to risk can lead to depression and other mental health concerns, says Malani.

How should you wear a mask when you need a booster? Do you need to unmask and laugh or just adjust our worries?

There are places where you might still need to wear a mask, such as health care facilities, although the rules may have changed. But that doesn’t mean you have to take it off. If you’re concerned, you can ask maskless staff to put one on. If you see a mask that isn’t good for public health, you can make a public health statement such as “a mask should go above the nose.”

The rapid development of effective COVID vaccines around the world has been a medical marvel. There will be new boosters often. But don’t necessarily expect to be prodded on your cellphone – one NPR reporter just get a message that his vaccine reminders will cease.

So with the emergency state over, you may have to pay attention to your own vaccine schedule rather than hearing calls from the government to go get your booster.

And public health specialists note that you shouldn’t just focus on COVID when it comes to vaccines. Dr. William Schaffner says to stay up to date with all vaccines. The first-ever vaccine for adults to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is expected to be available by September in the U.S.. There are flu shots and possibly a new booster. “Adults will want to talk to their doctors this fall about all the vaccines they need,” he says.

Source: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/05/12/1173993754/coronavirus-faq-emergency-over-do-we-unmask-and-grin-or-adjust-our-worries

What Do I Need to Know When I’m Going Through a New Window? Dr. Malani, MD, a Social Worker, and an Advocate for Coronaviruses

Loneliness is more of a pain than you can imagine. Yeah, well maybe that’s not a big surprise — but the pandemic reinforced the toll that a lack of social contacts can take on mental health.

Dr. Malani is the lead researcher on a January 2023 survey of more than 2,500 people ages 50 to 80 conducted by the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation and supported by AARP and Michigan Medicine. The survey found that one in three people between the ages of 50 and 80 say they sometimes or often experience loneliness.

She says that people at risk of severe disease from COVID-19 should consider taking precautions, such as online conversations and meeting outside, to avoid isolation even though the risk of transmission is lower.

Some people who were treated for cancer years ago are still concerned about their risk. “A talk with your doctor can help you determine risk and precautions to help you engage with people and activities you enjoy.” On a personal note, she says she masks when caring for patients but otherwise generally does not mask in meetings or even while traveling these days. “I pay attention to how I feel and am careful about not exposing anyone if I have any symptoms at all, even if mild,” she says.

Consider testing if you have been exposed to someone with the virus or have symptoms that could be COVID-19, especially if you fall into a high risk group, say the doctors we interviewed. And hang onto those masks. You’ll want one if someone in your home tests positive so you can protect yourself — and protect others if you test positive.

We are indebted to all the medical professionals who answered questions for the coronaviruses FAQ series, even as many of them put themselves at risk of infectious disease while caring for patients.