The virulence molecule ferries into human cells

Using a syringe-like molecule to target specific cell types: Re-engineering injection complexes in the bioluminescent bacterium Photorhabdus asymbiotica

The research and treatment of disease could be improved with the ability to deliver specific genes to specific cell types. The challenges of trying to target cell types of interest and the ability to transport a certain type of molecule across the cellular membranes have made it difficult for the development of such tools. Writing in Nature, the team states that their invention is a device found in the bacterium Caenorhabditis elegans. Building on a growing body of knowledge regarding the mechanisms that mediate bacterial interactions with cells, the authors show that this approach can be tuned to target specific cells and to deliver customized protein cargoes (payloads). Re-engineering injection complexes is a biotechnological toolbox that could have applications in various biological systems.

“It’s astonishing,” says Feng Jiang, a microbiologist at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Institute of Pathogen Biology in Beijing. “It is a huge breakthrough.”

The technique, published in Nature on 29 March1, could offer a new way to administer protein-based drugs, but will need more testing before it can be used in people. With further optimization, the approach might also be useful for delivering the components needed for CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing.

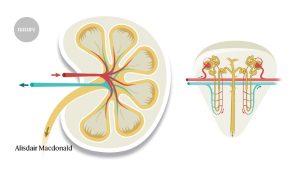

Last year, Jiang and his colleagues reported that they could manipulate this syringe-like system in the bioluminescent bacterium Photorhabdus asymbiotica, loading proteins of their choosing from mammals, plants and fungi into the syringe2. Normally, the bacterium lives in the nematodes and uses its syringe to deliver a toxin into the cells of insects. The insects are killed by a toxin and eaten by a nematode. The co-author says the bacterium is viewed as a hired gun to kill the insect.

In Zhang’s lab, Kreitz and his collaborators were working on ways to engineer the P. asymbiotica molecular syringe so that it would recognize human cells. The tail fibre is a part of the syringe that binding to a molecule found on insect cells. The team used AlphaFold to modify the tail fibre so it wouldn’t recognize mouse and human cells. “Once we had the image, it was very easy to modify it for our uses,” says Kreitz. “That was the moment when it all came together.”

The toxins that were loaded with the syringes were put into the cells in the lab and into the brains of mice.

The syringe story is reminiscent of the way that researchers such as Zhang developed CRISPR–Cas9 — a system that many microorganisms rely on in nature to defend against viruses and other pathogens — for use as a genome-editing technique, says Asaf Levy, a computational microbiologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Only a small number of labs study the bacterial needles compared to the early days where they were used in research.

They can have a transformational effect on medicine, says Levy. He says the evolution of this thing is amazing. “The fact that you can engineer both the payload and the specificity is ultracool.”