The Georgia Senate race is something that will not go away quickly for black Americans

The Second Black Football Player to Win The U.S. Senate Seat: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Death in 2024 and the Death of Jon Ossoff

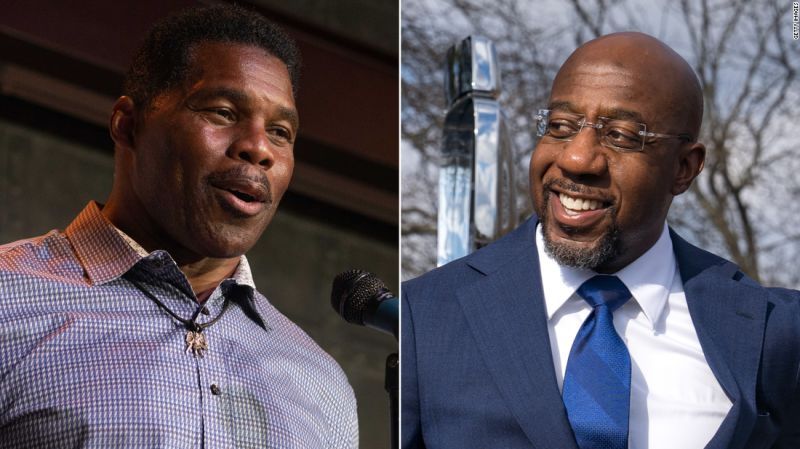

The US Senate race between Raphael and Herschel was a tough one to watch, observe and analyze, as a black man. The assumption that a Black football player whose celebrated symbolism in Georgia would be enough to split the Black vote thankfully went unrealized, but the reality that a number of White Georgians were willing to support Walker underscores the troubling questions ahead for a country mired in division and bracing for former President Donald Trump’s bid for his old office in 2024.

I am relieved that the pastor of the church where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta were married defeated an unqualified contender and won a full six-year term. His victory in a closely fought race was a triumph of substance.

Walker possessed absolutely no credentials to become the Republican Party’s Senate nominee, other than being a famous former athlete friendly with Trump.

I grieve for the parts of America that enthusiastically embraced Walker’s candidacy. People who supported him will not soon forget the message he sent to millions of Black Americans.

On January 5, 2021, Warnock became the first Black person elected to the US Senate from Georgia in American history. Jon Ossoff, who became the first Jewish senator from the state, and the historic victories of others were overshadowed by the tragedy that occurred the next day.

The 1619 Project: A Multimedia Project on Black Women and Black Women: Challenges for Democracy, Discrimination, Segregation and Violation

The first two episodes of “The 1619 Project,” a documentary series which premiered on Hulu on Thursday, brings to life the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times multimedia project created by Nikole Hannah-Jones.

In the first two episodes of the 1619 Project, it’s made clear that Black people’s relentless buying, selling, insuring, and financing would help make Wall Street and New York City the financial capital of the world.

At the same time, these episodes also reveal how Black folks represent American democracy’s beating heart; that heart has helped fuel the imagination and social transformation that has helped uplift not only African Americans, but also women, other people of color, LGBTQ+, immigrants and the disabled.

The multimedia educational social media supporting materials and the bestselling anthology of the documentary series are provided more details to the original New York Times Sunday Magazine.

America is trapped in historical amber and is stuck in cruel myths and violent realities that perpetuate racial division, economic inequality, segregation andviolence on the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Hannah-Jones says in the first episode that the challenges for democracy are to tell a full story of American history. Her framing puts modern-day voter suppression tactics, ranging from disallowing voters from receiving food and water on long lines to allowing anyone to object or challenge a voter’s ballot in states like Georgia in crucial historical context that links past and present.

The first successful political coup in American history occurred in 1898 when White racists killed and humiliated Black political leaders in the city, taking place in the midst of Reconstruction.

The episode’s focus on both enslaved Black women and their modern contemporaries allows us an intimate glimpse into the racial and sexual reproductive realities Black women have confronted throughout American history. A Georgia plantation where Black women were raped by White owners who enslaved their own children added more to their fortunes, as it was detailed during a detailed examination.

Our racial identity is listed on certificates of birth and death. They are markers of future prosperity for some and punishment and premature death for others.

Forced reproduction laboring in unspeakable work conditions resulted in precarious Black pregnancies, where Black women were forced to give numerous births against the backdrop of high rates of infant mortality and generational trauma. Maternal mortality and infant mortality are linked to the challenges women had giving birth during slavery, according to historian Daina Ramey Berry.

It’s an incredibly painful history that is necessary in our own time. Serena Williams nearly died from a complication after giving birth to her daughter, and it may be possible to explain how a black woman like that is rich and famous.

We need to look back at what we commonly refer to as Legacies, but we need to confront a history thatactively marginalizes Black life in America and thus represents a threat to the democratic future of the country.

In the summer of 1966, America’s top civil rights leaders had descended on Mississippi for what became known as the Meredith March. The group left Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi to participate in the voting rights march begun by James Meredith. Meredith had been shot by a White supremacist and hospitalized with severe bullet wounds.

He counted the number of times he had been imprisoned in the South while a student at Howard University. He was going to adopt a defiant new slogan after he was released, as Willie Ricks had been testing it in small churches along the route.

“Black Power!” the crowd shouted back. Black Power is something we want. Carmichael cried again, five times in all. “Black Power!” the crowd screamed back each time.

A short Associated Press story about the scene was picked up by more than 200 newspapers. Overnight, the Black Power Movement was born.

The aim of the Black Power Movement was relatively modest and indicative of attempts by an impatient young generation to address systemic problems, even after the legislative gains of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Two college students in Oakland, California created a group called the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense because they took the same logo. The issue of police violence in Black communities was the focus of the Ten Point Program drafted by Bobby Seale and HueyNewton.

When the panthers first donned their jackets and berets, they were trying to promote their plan to use California’s open carry gun law to create armed civilian patrols to protect the city of Oakland.

When King tried to bring his peaceful playbook to Chicago, with a focus on housing, he encountered a White counterattack as vicious as anything he had witnessed in the South. In the 1966 midterms elections, a White “backlash vote” helped elect Ronald Reagan to the statehouse in California and propelled a rightward swing that set the stage for Richard Nixon’s law-and-order campaign two years later.

A group of people from a right-wing group wanted to expel all White members from SNCC but they were denied at the group’s headquarters, which is located in the Catskill Mountains. After only one year as chairman, a spent and somewhat less-than-charming H. Rap Brown stepped down, leaving behind even more inflammatory rhetoric and a successor that was not much more than a name.

The Black Panther was consumed by another vicious cycle. In order to win release from prison in 1966 Cleaver collaborated withNewton and Seale and wrote “soul on ice” which would be published in 1973.

A second lesson is to be prepared for fierce backlash to any temporary progress. A student of 1966 would not be surprised to see how quickly police reform started to stall in the face of a concerted campaign to demonize “wokeness” and calls to defund the police.

And those aren’t the only essays I was thinking about long after finishing the book. “Black, But Not Beautiful: An Aesthetic Dilemma” shows how “whiteness is inherently supreme, and blackness is, by definition, unruly, undesirable, and unholy.” Black looks at popular culture to explore the idea that it’s hard for Black people to see themselves as attractive in a society in which beauty standards are “diametrically opposed” to their features. “When We See Us” is a film that is a perfect companion piece to “The Trial and Massacre of the Black Body.” Through the lens of “When They See Us,” Black explores the justice system through the eyes of people who have experienced it. “Beauty and Struggles of HBCUS” shows how HBCUS and those who work and teach in them tackle the monumental task of convincing students of their intellectual prowess, which is something that, in most cases, no one has done to that point.

“The Trial and Massacre of the Black Body” is a brilliant essay about George Floyd that asks the same question we still have to ask regularly: “…not whether a black person is dead, but whether the police we see committing the act will be held responsible.” The shield of cultural protection that surrounds white male patriarchy and power, and the way it often leads to the murder of Black individuals, is exposed time and again by Black, as well as a scholar. Perhaps the most painful essay to read, this one is packed with examples that show the perpetuation of racial abuse and unfettered discrimination against Black people despite the outcome of the Floyd case. Black leads the readers on a painful tour of the deaths of people whose deaths were linked to unfettered racism.

It’s important for stories to be kept out of the American narrative as it robs us of important historical lessons and warps our vision of ourselves and our future.

Learning from Garvey: The Case for a Black Star Line Shipping Company, and how to prosecute a racist, xenophobic criminal

The Jamaican-born Garvey called for an end to colonialism in Africa, for economic justice for the entire African Diaspora and for cultural and political recognition and independence in 100 years ago, which was a time when such declarations were just about unheard of.

As part of his push to provide economic opportunity and autonomy for Black people, Garvey started the Black-owned and -operated Black Star Line shipping company, stylized after the White Star Line, which owned the Titanic. Garvey’s ships, in theory, could have helped transport Black people back to Africa, facilitated trade throughout the diaspora and instilled pride while providing a vision of economic empowerment.

In fact, even the initial charges can be traced directly to espionage and efforts to infiltrate the Black Star Line by J. Edgar Hoover, who hired some of the first-ever Black Bureau of Investigation agents in order to stop any “Black Moses” figures like Garvey from succeeding. Hoover wrote about his search to find a charge that would allow the government to deport Garvey, settling on mail fraud when other grounds for charges were unsuccessful.

We failed to learn from Garvey’s story. That’s largely because mainstream narratives rarely teach about his legacy, and when they do, they usually fail to correct the historical inaccuracies promulgated by his wrongful conviction. By failing to learn the lessons from Garvey’s case, and by underestimating the harm of politically motivated infiltration and prosecution, we open the door to continuing these policies and practices. For years to come this will result in shame.

Garvey’s legacy is also relevant today because we see the same tactics — espionage and politically motivated charges — being deployed against Black leaders attempting to organize against the status quo. In the years after the George Floyd uprisings Black Lives Matter protesters were identified as Black Identity Extremists by the FBI, while in 2020 they were involved in a movement of their own with an unknown number of people from other countries.