Scientists will sequence Beethoven’s genome for clues

The Heiligenstadt Testament: Beethoven’s long struggle with hearing loss uncovered by Krause’s genetic sequencing of 17 years after his death

But Beethoven outlived his favorite doctor by 18 years, and after the composer died, the testament was discovered in a hidden compartment in his writing desk. In the letter, Beethoven admitted how hopeless he felt as a music composer struggling with hearing loss, but his work kept him from taking his own life. He said he didn’t want to leave ”before I had produced all the works that I felt the urge to compose.”

Beethoven wrote a letter to his brothers in 1802 asking that his doctor determine and share the nature of his “illness” after he died. The letter is known as the Heiligenstadt Testament.

If Dr. Schmid is still alive he should write something in his name to describe his illness so that the world may get to know him after his death.

Beethoven’s genetic data also helped the researchers rule out other potential causes of his ailments, such as celiac disease, an autoimmune condition, lactose intolerance or irritable bowel syndrome.

His work has ensnared countless listeners, including Tristan Begg, a biological anthropology PhD student at the University of Cambridge, and one of the researchers involved in the genetic sequencing project.

Begg was 17 years old on Christmas day in 2007. One of his presents that holiday was a record player. When he placed the needle on Beethoven’s masterpiece, his world would never be the same.

“It really just hit me. It was the first ‘dun dun dun,'” Begg says, referring to the melody that subtly but powerfully surfaces after half a minute. “I heard that… I had to stop crying and catch myself. That sparked this obsession, both with the music and with the man.”

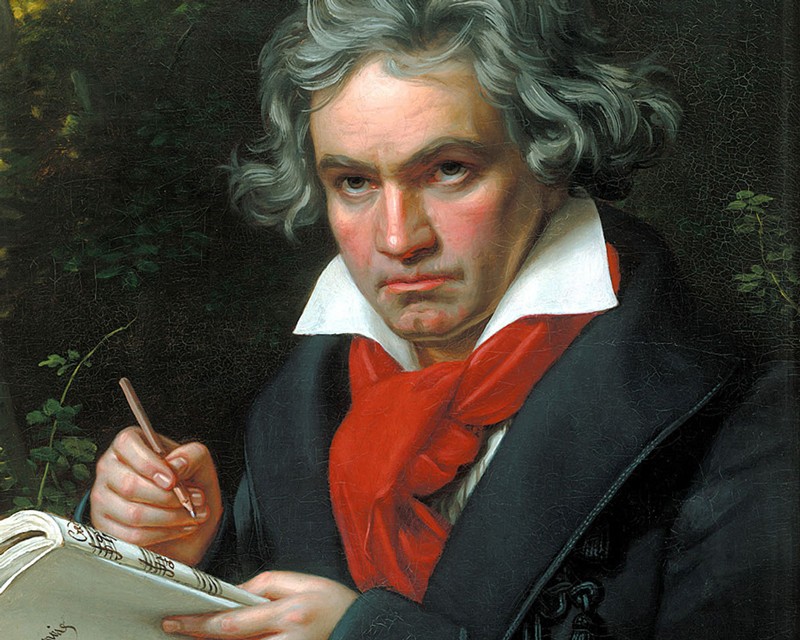

“Our primary goal was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him being functionally deaf by 1818,” said study coauthor Johannes Krause, a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, in a statement.

He had a set of GI issues. Begg said these were frequent attacks of irrmidation. They could last a long time. They were accompanied by some pains in the colon.

“However, we did discover a number of significant genetic risk factors for liver disease,” he added. “We also found evidence of an infection with hepatitis B virus in at latest the months before the composer’s final illness. Those likely contributed to his death.”

How did Beethoven start his DNA? What happened to Beethoven and what happened after he was born, and how did Beethoven end up dying of cirrhosis?

“Your genome begins in the enormous stretches of DNA,” says Begg. But “the average fragment length of the DNA we were getting from these hairs was about 15 nucleotides long” — super short pieces.

The DNA sequencing task confronting Begg, therefore, was like reconstructing a vast multi-volume encyclopedia from a couple hundred thousand sentence fragments.

He found out that there were three different people who produced the three locks of hair. Begg didn’t know that one was authentic at the time.

On its own, the gene’s not too concerning. If you’re consuming a lot of alcohol, it will become a problem. And that’s something that Beethoven likely did according to numerous accounts.

And all three factors — the gene, the drinking, and the hepatitis B — they would have all interacted. “Whichever way you cut it,” he says, “it really comes as no surprise he died of cirrhosis, ultimately, at the age of 56.”

The discovery of a sonata by Welch’s father: the birth of the composer Hendrik van Beethoven in 1572 and Mozart’s 1770

George Church, a molecular technologist at the Harvard Medical School who wasn’t involved in the study, says it’s solid research. He just wished the DNA had yielded more answers.

“I think the disappointing thing was the lack of explanation for hearing loss,” says Church. It is not the fault of the authors. It’s the fault of the specimens.”

The researchers think the affair happened between the 1572 conception of Hendrik van Beethoven, an uncle of the composer, and the conception of Beethoven in 1770.

The study can bring the composer to life. The man’s struggle in his physical body was a real thing, which is something he feels when playing Beethoven’s music.

He is completely in another frame of mind from anything his predecessors were to write, which is the difference between his earlier piano sonatas and these ones.

“The demands he puts on the performer are really extreme,” explains Welch. “It sounds very natural to the listener. You have to fight through passages in order to make the performance as cohesive and coherent as he wants.

Mozart’s DNA: Where do we go from here? Where are we going? How did Beethoven start his symphony, and what happened to his death?

As for Begg — who spent years wading through Beethoven’s DNA — he says that now that his genetic opus has been published, it’ll be Beethoven’s Eroica (his third symphony) that he’ll listen to first.

It takes a while to get used to, but it is an amazing piece of music. He doesn’t waste a note. He doesn’t waste time. Your feelings are taken care of.

The five hair samples helped scientists discover insights about family history, chronic health problems and what might have contributed to his death at the age of 56.

Medical historians combed through Beethoven’s letters and diaries, as well as his autopsy, notes from his physicians, and even notes taken when his body was exhumed twice in 1863 and 1863 with the hopes of figuring out his complicated medical history.

It’s not easy to get genetic material from old hair. The sample material alone is admirable according to Christian Reiter, a forensic medical specialist at the Medical University of Vienna.

Molecular biologist and historian, Walther Parson, in the research of Beethoven and the discovery of two children of the last Tsar of the Russian Empire

According to Beethoven’s friends, the composer used to consume alcohol frequently. According to a close friend, Beethoven ate lunch with a liter of wine every day.

The work is “a great technological achievement”, says Walther Parson, a forensic molecular biologist at the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria who has worked on other historic cases. These include the identification of two children of Nicholas II, the last Tsar of the Russian Empire, from remains discovered in 20072.

Ian Gilmore, a liver specialist at the University of Liverpool, UK, says that the hair analysis points to various potential causes of liver cirrhosis, and “the truth probably lies in the interaction between several of these”.

“Medical genetics struggles with the same problems in patients that are alive today,” says Parson. The causes for a disease are not explained by the DNA sequence.